Out of the Box #6

Live '94

Out of the Box is a bi-weekly series focusing on seven inch records. It’s an excuse to engage with my collection in a new way, as well as to write about older records and genres we don’t often cover at ACL.

OUT OF THE BOX #6

MEV ~ Live ‘94 (1995)

Two short tracks from the 90s, from a group best remembered for its long collective improvisations from the 60s. So this little curio is notable for that as much as anything. But Musica Elettronica Viva [Italian for “live electronic music” in case that weren’t clear] or MEV continued in various forms up until recently, so fans of the group are likely to be familiar with recordings from the first two decades of the 21st century, a period in which the group had mostly been reduced to a core trio pursuing much more subdued but equally subversive music. They continued to be active during the 1970s-1990s, fewer MEV recordings from those decades have been released, even if solo compositions by the various members proliferated. So again this seven inch offers an interesting window into a lesser known period of the group’s history.

MEV began in Rome in the spring of 1966, as an experiment in collective improvisation. In 1968 they opened their studio in Trastevere for their Zuppa, welcoming anyone to join their improvisations, and incited audiences to participate in the collective creation of spontaneous music with the Soundpool. While several of MEV’s key members from their Roman period (1966-1970) were themselves amateur musicians, the American ex-pat trio of Alvin Curran, Fredric Rzewski, and Richard Teitelbaum all had the privilege of Ivy League education and foundation fellowships which brought them to Italy. And yet the commitment to working outside of traditional institutions wouldn’t have been a very powerful renunciation if they weren’t already working inside. It isn’t a refusal is nothing was offered. Anyone could toil away in obscurity, but to reject the tradition of western art music, to renounce the piano (even if it proved to be temporary) has more weight when such a renunciation comes from insiders. Still, this period could only last so long, and eventually Rzewski and Teitelbaum returned to the US, and, despite some short lived spin offs, MEV performances became a periodic but infrequent occurrence over the next few decades.

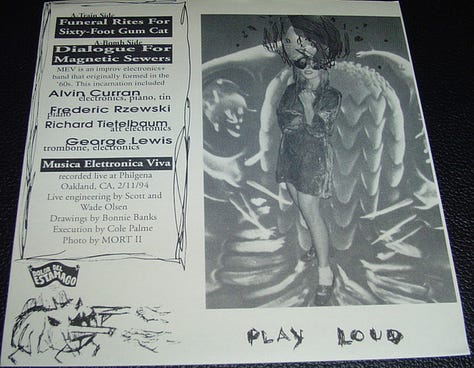

Live ‘94 features the core trio with additional trombone and electronics courtesy of the great George Lewis, who first joined MEV in the late 1970s even if he’s not always the first name associated with the group. (The only other publicly available recording featuring Lewis that I am aware of is “Ferrara, Italy (2002)" included in the set MEV40, as part of an ensemble that also includes longtime MEV associates Garrett List and Steve Lacy.) Each side here is a bit over 7 minutes in length, both excerpts from an improvised reunion concert recorded live at Philgena in Oakland, California on February 11, 1994. So, relatively long cuts for a seven inch but quite a bit shorter than official recordings issued by MEV. Curran had been teaching at Mills for half the year since the 1980s, so one might speculate that there’s a Mills connection here, but I’ve not been able to dig up any information about the venue or performance, or indeed very much at all about the label, a mystery about which more later.

So how does it sound? Let’s get into. Also note the imperative to “Play Loud” on the back cover.

The A-side is called “Funeral Rites For Sixty-Foot Gum Cat,” less descriptive perhaps than early works such as Spacecraft, and less formal than the straightforward Symphony #s that title their later works. The title does convey a bit of the humor and irreverence that I associate with Curran’s work in particular, though it’s also likely that the titles were chosen by the label. In anycase, the recording begins with dueling pianos set against an electronic loops, dropping the listener in medias res amidst a swirl of chaotic and clashing sounds. A brass melody briefly punctuates the noise only to vanish again. While the bass piano notes provide some grounding, the forward momentum never quite coheres into a beat let alone any kind of groove. The trombone really blares towards the end of the track, winding down for a quieter passage to end the side, but not before a bizarrely endearing squawking melody reappears. The energy of the live performance comes through, conveyed in the poor sound quality and audience whispers but also in the audible experimentation between the members. Afterall, this is improvised live electronic music, and that entails taking risks.

[Note: It seems to me that these videos are mislabeled, unless my copy of the record had the stickers placed on the wrong sides.]

The B-side, “Dialogue For Magnetic Sewers,” opens with a cacophonous crash followed by an electric drone which blends into an unsettling piano and brass passage. Overall this segment seems less discordant but more ominous nonetheless. The trombone is more forceful and confident, quickly instigating the piano to more furious vamps. By the middle of the side, the dueling pianos have created a pleasant rain of notes, but this peters off into one of my favorite moments on the record, particularly as the use of electronics comes to the fore as the pianos trail off. Brass and electronic stabs puncture the quiet, alternating with more piano trills, ending with Teitelbaum’s queasy electronic drone and one big collective cacophony to send us out.

Now a bit about the label that released this record: Dolor Del Estamago (Stomach Ache Records). Aside from their discogs page, I’ve been unable to find very much information on this “mysterious Mexican record label,” and I wonder if it really was Mexican, since technically it should be estómago, and that seems like a telling misspelling. Maybe a gringo moved down there and started the label, or maybe it’s a misdirect. There is indeed an associated address in Tamaulipas, Mexico, but then there was an addresses in New Hampshire. Looking through their catalogue it all feels very Bay Area to me, possibly someone associated with Mills College, which tracks in this case given the nature of this live recording of MEV. Very little about this label seems to be out there. There is some speculation on a message board that the label was a joke, perhaps due to fake or very obscure catalogues.

According to Discogs, their catalogue includes releases Gordon Mumma, David Tudor, John Cage, Xenakis, Pierre Henry, LA-punks The Screamers, infamous provocateur GG Allin, an unusual split between Serge Gainsbourg and Conlin Nancarrow, Thurston Moore, The Gerogerigegege, and many other noise artists from both sides of the Pacific. That is an interesting and impressive sampling, however it seems much the rest of the catalogue is less noteworthy and many of those releases which are were unofficial or bootleg releases, which may go aways to explain why the label is so shrouded in mystery. Next time I speak with Curran I’ll ask if he knows anything about this record and if it was authorized or not.

Much of the artwork on their releases is credited to Bonnie Banks, which might be a lead to follow. If anyone knows anything further, please do comment or DM me.

One of the core members of Musica Elettronica Viva is Alvin Curran, now the sole-surviving member following the recent passings of Richard Tietelbaum and Fredric Rzewski. After all these years, Curran is still based in Rome, where I interviewed him for my dissertation several times in the spring of 2019. Episode 12 of the Sound Propositions podcast, MAKING YOURSELF DISAPPEAR, features some of those interviews, though mostly we discuss his recent work, in particular the sound installation he did at the Terme di Caracalla.

My dissertation, The Refusal of the Work of Art: Aesthetics and Autonomy in Italy, 1965-1985, explores the nature of doing things together through a cultural history of aesthetics and politics in post-1968 Italy, organized around a theoretical investigation of the concept of work. Chapter 2, “The Revolution is in the Streets: Performance, Action, and Collective Creation,” tracks the literal movement of art onto the streets in the mid-1960s, which catalyzed an aesthetic turn towards performance, as theatre troupes, artists, and workers reclaimed public space as a site for experimentation and interaction. There I analyze the work of Musica Elettronica Viva alongside that of The Living Theatre and Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Lo Zoo as paradigmatic of this shift, representative of differing approaches to collective creation and audience participation. This context is just to say that I’ve written quite a bit about MEV, most of which is unpublished at this time, so I’ll draw on that chapter here to say a bit more about the group than I normally would in this space, for paid subscribers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to a closer listen to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.