Why Do We Do This?

Sometime during the pandemic, my friend Stefan moved into a new apartment, sparking a conversation between us about physical media. Why do we do this to ourselves, we both wondered, why keep lugging boxes of records, tapes, and CDs around, when we hardly ever listen to a tenth of them? What’s the use?

In the last decade I moved from Montreal to Minneapolis and back, with the better part of a year somewhere in there spent in Europe, during which time most of my stuff was in storage in Minnesota. After initially moving to Montreal from New York, I’d previously left and returned once before, during which time I was forced to leave two long milk crates of 12”s with my friend Francois for safe keeping. Digital files aren’t exactly immaterial, but I’ve never hurt my back carrying hard drives. Seriously, records are heavy, especially when you live up a couple flights of stairs. And I didn’t grow up with money, and I don’t have much now, so buying physical media is certainly not the most financially responsible decision. &yet&yet…

In 2019 I reposted an article I’d written for ACL, “The Problem with My Husband’s Stupid Record Collection,” as “On the Pedagogical Organization of Record Collections,” including an addendum where I muse a bit on collecting physical media:

Record collecting is about meaning, not function. This is why the impracticalities (of, for instance, moving dozens of boxes of books, thousands of pieces of vinyl, etc.) is not a rational decision. The functionless accumulation, the great (literal) weight of storage. This of course has become part of the fetish. Our vinyl weighs a ton.

So, I’ve thought a lot about why people like me hang on to books, records, CDs, tapes, vinyl, etc. On the one hand, when the pandemic hit I felt very prepared. “This is what I’ve been planning for!” Still, lugging all those boxes takes a toll, and at some point it begins to feel pathological. Why hold onto all this stuff? But like many before me, I’ve simply made my peace with being a media hoarder. I’m an archivist, a caretaker, a temporary steward working on behalf of future generations. Or so I tell myself.

So then, how best to organize one’s collection?

Personally, I prefer a combination of genre/style, chronology, and idiosyncrasy, especially if you actually want to dig and play records regularly. If you know you’re looking for a particular record, perhaps alphabetical is the way to go, but I would bet anything that this means the majority of records go forgotten and unplayed. This isn’t necessarily a problem in itself. The instinct of the collector is about more than the collection itself. When Walter Benjamin was asked if he’d read all the books in his library, he famously replied “Not one-tenth of them. I don’t suppose you use your Sèvres china every day?”

The pithy remark by the early 20th century critic, itself a quote from Anatole France, is one I’ve often deployed when someone walks into my living room and inevitably glances at the bookshelves and asks, “have you read all these?”

And why do we collect at all? In his 1968 book The System of Objects, Jean Baudrillard attempts to make sense of this question. In the section “A Marginal System: Collecting” he argues that every object has two functions, to be used and to be possessed. Possession, unlike utility, is not a practical matter but a means of subject formation. That is, investing our energy in collecting is also an investment in our emotional state, status, and individuality through these objects. A sense of property and ownership allows us an outlet, an aspect of control over what might evade other facets of our life.

These are my records. Together they construct a world, a “private totality.” Like the 90% of Benjamin’s library which goes unread, “the pure object, devoid of any function or completely abstracted from its use, takes on a strictly subjective status: it becomes part of a collection.”

This new series, Out of the Box, is partly a response to all of the above. While I still am not convinced that a collection should have some utility, I’ve decided to make an excuse to engage with my collection in a new way, publicly sharing selections from my collection. It’s also an excuse to write about older records, and genres we don’t cover for ACL. Though inevitably we’ll wade into more familiar water, at least initially we’re going to be looking at some punk and hardcore seven inches.

When I was young, a had just a few CDs. I got a CD player for Christmas around my 9th birthday, and it was a big deal. I’d never had my own means of listening to music, and I think we can relate to the freedom granted by headphone listening. CDs were really expensive then, especially if you were a kid. By the time I was 13, I had maybe ten CDs, and as I’ve written about before, discovering Epitaph Records’ Punk O Rama Vol. 2. changed my life. Not too long after I bought Victory Records’ Victory Style II, another formative moment. It’s not lost on me that both of these were sequels. I always felt, if not late to the party, then at least that there was so much more out there to discover.

This was before the internet. Back then we just got fragments of stories, and through bits and pieces you could catch a glimpse of a broader network. History was being constantly written over, like tags in a bathroom stall or stickers on the wall of CBGB’s. It was like picking up a comic book issue in the middle of an ongoing story. Out of context, you had no idea what’s going on, but it could still suck you in. And often what you imagine in your mind turned out to be more interesting than the real thing, but this was just motivation to get out there and Do It Yourself.

By the time I’d started high school, I had the occasional tape I’d purchase (mostly because they were cheaper than CDs) or a literal mixtape a friend had made. Much of my classic rock education came from friends and older cousins dubbing copies of Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Pink Floyd and so on. But it was seven inches that really made me a collector. They were cheap, larger than a CD and smaller than an LP. Something about them just grabbed me immediately.

And so it is to this underappreciated format that Out of the Box will be devoted, at least for a while. My collection of 7”s and 45s isn’t particularly impressive: three short boxes of records. But that’s more than enough to keep this column going for a long while. Let’s get into it.

OUT OF THE BOX #1

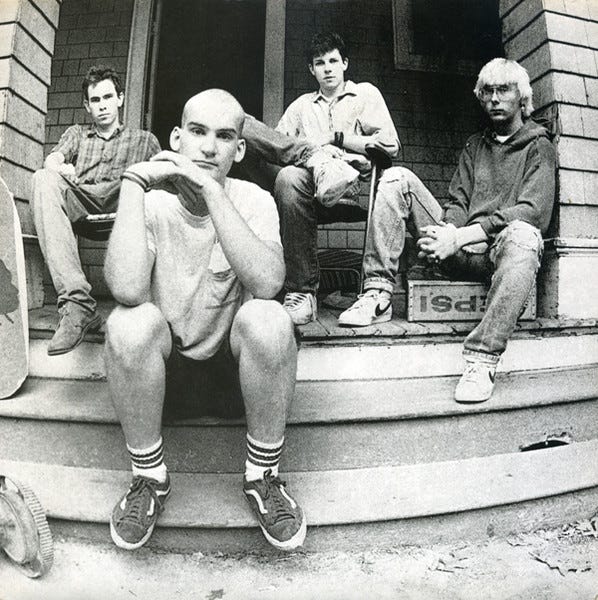

Minor Threat ~ Salad Days (1985)

My parents divorced in 1997, when I was 13, after which time my mom and brothers and I moved in with my old Italian grandma. Around that time, I claimed both my parents meager record collections as my own, as they were languishing in a moldy garage after the move. Along with an old turntable in need of a new stylus, and an equally old stereo receiver, I began my foray into vinyl. I vaguely remember scrounging some speakers off the curb walking around my grandma’s neighborhood. By the next year, after countless fights between my mom and her mother, we’d moved into a shitty apartment across town, and I claimed a dingy room in the unfinished basement as my own retreat, well into my punk phase by then. Once I had that system working, I could lose myself in the spiral groove. Unlike a 5-CD changer, which play indefinitely, a record needs to be turned, it requires our intervention. That rhythm appealed to me for various reasons. The revery was always temporary, before being called into action to flip the record or choose another. Maybe that’s why I still think of selecting and sequencing as the heart of DJing.

I bought this 7” during this period, sometime around 1998. Along with 7”s from Black Flag, Pennywise, NOFX, Bad Religion, and MXPX, it was one of the first 7”s I ever acquired, and therefore it was among the first vinyl records I ever bought.

The A-side, of course, is “Salad Days,” perhaps my favorite song in the entire Minor Threat discography (which is admittedly only about 26 tunes). Opening with a slow bass harmonic riff, before, at 18 seconds, diving into a driving bass line, later joined by a ringing bell and a memorable drum beat. The tempo is relatively slower, and the recording sees the band branching out into less typical instrumentation, if only barely, including the aforementioned bells and a layer of acoustic guitar. The lyrics aren’t particularly subtle, and it’s clear that Ian MacKaye was ready to move onto something new. Initially, he seems to be looking back wistfully at the past. “Wishing for the days/ When I first wore this suit/ Baby has grown older/ It's no longer cute.” But where does that leave him? He isn’t sure where he’s headed, just “On to greener pastures/ The core has gotten soft.” I discovered Minor Threat and Fugazi simultaneously, so it wasn’t hard at the time to hear a longing to move beyond the narrow constraints of hardcore. Even then, MacKaye had no illusions, and could see clearly that it was no heyday. Salad Days? "Do you remember when? yeah... so do I. we'll call those the good old days. what a fucking lie." Maybe this made me a cynical teeanger, but overall I think this was just the message I needed as I started high school. Enjoy it while it lasts, but don’t romanticize. The best is yet to come.

In retrospect, it’s kind of funny of to call these Minor Threat’s “slow” songs, but even at 151 bpm, it’s objectively true. Released a couple years after the band disbanded, it’s obvious by the stylistic shift and the lyrics that their time was up. All three songs are outliers in the Minor Threat discography, and in some ways, I’ve found the revisiting the B-side more interesting.

“Stumped” is the song that I remember the least. Like “Salad Days,” it too begins with a solo bassline. This time a plodding ascending/descending phrase is counterposed to the rhythm of mouth noises and rhythm guitar which are added in turn. The lyrical content is similarly wistful and discontented: “No way to go/ Which way to go?/ Where did we go?” MacKaye doesn’t seem to have an answer. (He’s stumped.) The originators of straightedge then inform us that “The time has come for everyone to party.”

“Good Guys (Don’t Wear White)” is a cover of "Sometimes Good Guys Don't Wear White" by The Standells, a ‘60s garage rock from LA. Ed Cobb gets the writing credit, also the writer of Gloria Jones’ "Tainted Love," which Soft Cell made a hit in 1981. So while other punk groups were going No Wave and embracing synthesizers and dance music, Minor Threat draws our attention to punk’s debt to early rock n roll. Both songs challenge conventional views and superficial iconographies. Life isn’t a child’s story where we can easily differentiate “good guys” and “bad guys” based on superficial markers. The differences between the two versions are subtle but worth mentioning. Occasionally MacKaye changes words; he substitutes “I'm a bored boy born in the road” for “I'm a poor boy born in the rubble,” “With all those rich kids and their lazy money” for “But those rich kids and all that lazy money,” and “White filth and easy living” for “White pills and easy livin'.” But the more telling changes are in what MacKaye leaves out. Minor Threat’s version is a reduction, it’s more minimal, it’s a distillation. The Standells’s singer uses many filler words—“Yeah,” “And,” “Baby,” etc—which MacKaye drops entirely, as with the entire last verse of the song.

Minor Threat’s Complete Discography CD puts “Salad Days” last, which seems fitting, as the song stands as a posthumous metacommentary on the group. I discovered Fugazi around the same time as Minor Threat, beginning with 13 Songs on vinyl. Maybe I’d heard “Burning” in a skate video, I can’t remember the actual first encounter, but I do know that from the first time I heard the opening bassline to “Waiting Room” I was hooked. And unlike Minor Threat, Fugazi were still active at the time, and my friends and I could (and did) drive down (twice!) to DC to see them play their free shows in Fort Reno park. But that’s a story for another time.