Dear Listeners, Joseph here, and you may have noticed my predilection towards covering Italian artists, and this installment from the Archives collects a bunch of my writing on Italian music, alongside a review by James Catchpole.

My grandmother (and all my great-grandparents) came to the US from the south of Italy, I first visited Italy myself as a college student in 2004. In a pre-social media, pre-smartphone world, I visited a few social centers in Rome that I looked up in the back of my Slingshot weekly planner. But on that first trip the only music I managed to encounter was kitschy folk music, faux reggae, and Euro-techno. By a few years later, after a while writing for the Silent Ballet, I had built up a network of contacts with artists and labels associated with the Italian post-rock and experimental electronic music communities, and by 2011 I was attending regional festivals like Tago Fest in Tuscany and connecting with the Neapolitan noisers and impro punks at Perditempo.

There wasn’t and isn’t an appropriate umbrella term or genre that unites such a diverse constellation of artists, but Italian Occult Psychedelia has come closest. Many contemporary artists, in Italy and internationally, have taken inspiration from Italian music and soundtracks of the 1970s, the imagery of horror films, Spaghetti Westerns, and ethno-documentaries, and the occult rituals buried in the history of Catholicism, particularly from the south of Italy. Heroin in Tahiti, a duo from the Pignetto neighborhood in East Rome, best exemplified the blending of these influences, a genealogy explored in great detail in member Valerio Mattioli’s 2016 book Superonda, a “secret history of Italian music” between 1964 and 1976.

It’s been nearly ten year’s since the release of Heroin in Tahiti’s magnum opus, Sun and Violence (2015). I spent a month in Rome that summer, and saw the duo perform in the basement of DalVerme in Pigneto alongside Toni Cutrone’s Mai Mai Mai. This post collects a blurb and full review of Sun and Violence, followed by an interview and profile of Cutrone. Of course there’s much more to Italy than that Roman scene, so I’ve also included an interview and mix from Onga, the man behind the influential Boring Machines label, and finally Sonic-Close Ups, Gianmarco Del Re’s two-part profile of the Milanese scene. And as a bit of a bonus, some excerpts from chapter 4 of my dissertation that touch on Italian Occult Psychedelia.

Heroin in Tahiti ~ Sun and Violence (Boring Machines)

This Roman duo pioneered self-described ‘death surf’ on their debut, but it was clear that the novelty of that idiom couldn’t sustain itself for very long. Rather than rest of their laurels, on their sophomore release Heroin in Tahiti push their sound into uncharted waters, a “spaghetti wasteland” of southern Italian folk music through the lens of psychedelic and prog-rock. The hype around Sun and Violence is easy to dismiss as overblown, that is until you actually sit down and let this 2xLP carry you away on a tour of the twin faces of Italian culture.

Sun and Violence is a remarkably executed and ambitious sophomore album from this Roman duo, a journey into the abyss of the Mediterranean psyche. Abandoning the Pacific flavor of their debut, they instead look for inspiration closer to home. Fusing folk rhythms from around the Mediterranean over beds of ambient sound, melodic psychedelic lead-guitar riffs serving to anchor the ship from steering too far off course. Heroin in Tahiti occasionally achieve levels of dramatic intensity, but are restrained enough that they never drift into aimless noodling or unfocused improvisation. Instead, each song is rigorously structured, and a strong sense of narrative propels the album forward. Samples were drawn from recordings made in Italy during the 1950s by noted ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax and Diego Carpitella, in a sense almost turning the gaze of the anthropologist around, “Othering” one’s own culture in the process. Sun and Violence is the soundtrack to an hallucinatory sun-bleached film noir, a modern mythologization of the dark side of Italy. (Joseph Sannicandro)

Heroin in Tahiti ~ Sun and Violence

On Sun and Violence, Heroin in Tahiti step out of the cool shade, substituting it for a scorching inferno. This is the band who gave us the seductive, yet bleakly pessimistic sound of instrumental death surf; a full throttle, dark and sultry reincarnation of surf rock. It’s surf music for a broken generation, the kind that can’t find any kind of solace. The sandy beach and the glistening waterfront have seen better days.

Surf’s long been in a state of caged slumber, but now it’s morphed into a different beast. The name gives it away – death surf is brutally dark music, and its terror is ever-present. Amity Island experienced the same thing forty or so years ago. In death surf, you won’t see any beautiful girls and there aren’t any surfers to ride the waves. There isn’t a surf-inspired, bright chord progression on the hazy horizon, but in a way little has changed: the clean electric guitars are still there, and they still glint over the clear cyan of the water. It may look pretty, but it’s still dangerous; you only have to look at the red-lettered warnings that litter the beach and read about the recent spate of shark attacks to discover as much. A dark paradise awaits all who are willing to take the trip.

Sun and Violence has tanned to the point of blackening. The squealing, sun-baked guitars have spent too long in the flammable heat, and they ride side by side with a set of propulsive drums. Heroin in Tahiti provide a couple of experimental interludes, and that keeps the music slightly unsteady, dehydrated and completely dry. The drums have vicious teeth that tear into the music. They surge and pound violently, running their bone-dry river of percussive blood through the dusty tributaries of passionate and loveless chants. Spent needles, severed crabs and broken shells litter the music.

Sun and Violence has been built on solid foundations; the music is a vast, unmovable canyon that has been there for thousands of years; it was just waiting for the right point of sunlight. In the Mediterranean, the music is bleak and yet intensely vibrant. Unlimited dark colors swirl and flow. The fiery drums bake under the intense heat. Bustling markets sit beside dusty roads that lead to other townships. The feeling of hopelessness is compounded by the coda “Costa Concordia”, which is named after the fated cruise ship that met its doom off the coast of Italy. The tropical slides and the lilting melodies conceal darker things; the “accident” led to several fatalities. Sun and Violence is an admirable continuation. Inside the jaws, the sun is obliterated; it might be the only way to escape the heat. (James Catchpole)

ROMA EST IS BEST

Perhaps best known for his Mai Mai Mai alter-ego, Toni Cutrone got his start as a drummer in bands including Hiroshima Rocks Around, Dada Swing, and Trouble Vs Glue. Outside of Mai Mai Mai, he is currently exercising his rock n roll soul drumming in the post-punk band Metro Crowd and a new performance-based project called Salò, after Pasolini’s infamous final film (itself named after the city where the Italian Fascist party retreated to in the final years of World War II). Beyond his work as a very active musician, Cutrone also runs No=Fi Recordings and has made a name for himself as an important concert organizer in Rome.

His venue Dal Verme [“of the worm”] became an important node in the Roman and international underground music community, renowned for its great cocktails, and excellent Meyer sound system (both of which are very rare in Italy, particularly in venues specializing in underground music). In 2016, in the lead up to municipal elections, the club was closed by the city, which invoked a Fascist-era law to shutter the venue, instigating an international outcry. Although it reopened shortly after, things were never the same and the partners made the difficult decision to close the club in 2017, after 8 years in operation.

Dal Verme’s rise coincided with the development of the Pigneto neighborhood in Rome as an eclectic center of cultural activity, from music to street art. Rome is so often associated only with the historic center, with the ruins of Imperial Rome, the history of the Vatican, and the corruption of Mafia Capitale. Despite all of this, all the politicians and priests and diplomats and tourists, the center can feel, somehow, sleepy, and for decades has lacked a sense of contemporary cultural energy. In a city which, in the 70s, was a hotbed of contemporary art and experimental theatre and dance, of the Estate Romana, this was a sad state of affairs. The plucky scene of outsiders in the East of Rome signaled that things were perhaps changing. This scene bubbling out of Roma Est began to attract international attention, but it was a scene much more defined by a shared attitude emanating from a particular neighborhood rather than a distinct genre or style. No=Fi’s 2011 compilation Borgata Boredom is a brilliant snapshot of energy of those years.

Nonetheless, journalists began to talk of Italian Occult Psychedelia, a term coined by Antonio Ciarletta in an essay for Blow Up magazine in 2012. Simon Reynolds and Valerio Mattioli posited the category as a kind of Italian analogue to Hauntology. Mattioli (a journalist probably best known to our readers as half of Heroin in Tahiti) finds that Italian Occult Psychedelia “avoids the eerie and pastoral feeling of the English counterpart, as well as the pop-cheesy attitude of the American hypnagogic pop. On the contrary, their music is blatantly dark, esoteric and sometimes bloody.” This music emerges just as young Italians were rediscovering the remarkable body of work produced in Italy in the wake of 1968, drawing connections between psychedelic prog rock, avant-garde composition, free improvisation, “ethnic” music, library music, and film soundtracks. The flood or reissues and pirated music allowed these various styles to be perceived as a kind of canon, a genealogy, to inspire a generation again in upheaval.

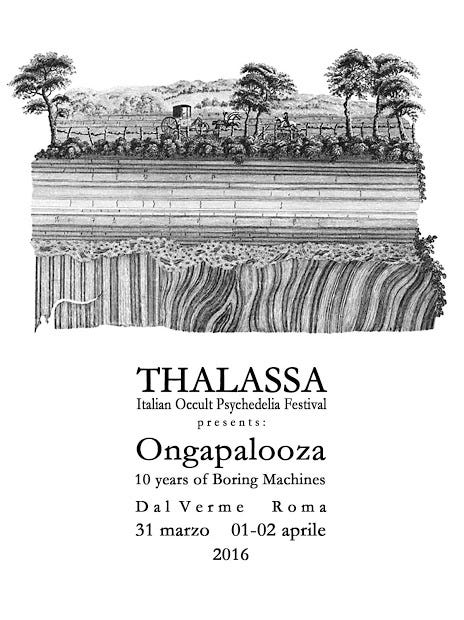

While IOP shouldn’t be strictly conflated with the scene in Pigneto, there is some overlap and IOP did find an important center in Dal Verme, which hosted the THALASSA festival, one of the key meetings of artists grouped together under this heading. Cutrone’s label No=Fi also released The THALASSA Tapes compilation, the closest IOP has to a statement of intent, as well as records by many artists who might fall under that banner.

These scenes, the eclectic one which coalesced in Pigneto and IOP, were nurtured by geolocated spaces and labels. All of Cutrone’s activities speak to this kind of nurturing connectivity. Mai Mai Mai’s music is made by Cutrone, often incorporating samples from ethnographic recordings and films, but Mai Mai Mai, whom he speaks about in the third person, is not solely the fruit of Cutrone’s imagination. Visuals are an important part of the project, with costumes for the ritual made by Canedicoda and live films made by Simone Donadni. Collaboration runs through all of Cutrone’s work, and it’s not for nothing how often he invokes his network of past and present collaborators.

Adapted from Sound Propositions Episode 7: IN THE SOUTH – with Mai Mai Mai [podcast]

LCNL 070: Ongapalooza – 10 years of Boring Machines mix

Our friends at Boring Machines records are about to celebrate their tenth anniversary! That’s ten years of championing great Italian artists to audiences around the world. Founded by Onga in Treviso in 2006, the label has been responsible for some magnificent records in the decade since. Onga has collected nearly two hours worth of material from 22 records to produce this amazing mix to share with our readers.

In addition to this mix, Boring Machines has a whole lot else going on to celebrate. They’ll be re-issuing their first release, My Dear Killer‘s CD Clinical Shyness on a limited run of tapes. And throughout the year anonymous LPs pressed in 10 copies will be announced without revealing any detail on the music they contain. Onga insists that “after ten years of spreading the best music that comes from Italy, we honestly think people should just trust our tastes, it’s a one-off, grab it or lose it thing. All the releases will have the same black cover, with just the number 10 in different color screenprinted on it.” Keep an eye on their website!

And perhaps the most exciting news: Ongapalooza! That’s right, East Rome’s Thalassa Festival of Italian Occult Psychedelia will feature performances from Fabio Orsi, Squadra Omega, Father Murphy, Heroin in Tahiti, Luminance Ratio, Mai Mai Mai, and many others. If you can get to Roma for 31 March-2 April, don’t miss it. Read the full line-up and more information here. Please join us in congratulating Onga and Boring Machines, and enjoy the music. (Joseph Sannicandro)

MINI-INTERVIEW

Congratulations on 10 years of Boring Machines! Ten years of anything is no small thing, let alone an independent record label. Perhaps you can share a story about how you came to found Boring Machines?

Well, thank you! Sure 10 years seems a long time these days, when a lot of projects are born and die within few months. In 2003 I met for the first time My Dear Killer and the project who then became the first incarnation of Father Murphy. I was doing shows in a basement and I was astonished to hear Stefano’s MDK songs: so raw, uncompromising, full of anger and discomfort. Father Murphy and some other friends had a label at that time, called Madcap Collective and I was helping them with some practical stuff on design and packaging of their releases. That’s when I learnt and start loving all the processes behind the release of a record. In 2006, together with Madcap Collective and other friends from the underground scene, I decided to try my way and I planned the release of my first record: My Dear Killer’s Clinical Shyness.

Since then I released 67 records in various formats, mostly CD and LP, many of which are co-released with other fellow labels.

I’d love to hear about what was most rewarding from the last decade, as well as some of the challenges you’ve faced.

There has been some highs and lows of course, both can be summarized looking at the sales stats of the label. One of the most satisfying things is seeing that almost 50% of the sales comes from abroad, which means that the mission to promote Italian music outside our country is accomplished, counting the fact that I can’t afford to buy a lot of ads, or PRs. It’s a reward for all the nights I haven’t slept, all the holidays I haven’t done to save money for a good record.

The stats also tells that you don’t sell many records actually, much less than you could think of when you plan a release. Some releases are sold out, OK, but it’s 500 records. When I was a kid you sold 500 records in your neighborhood. But that’s a very complicate topic to discuss. When I started I knew already the toy was broken, scarce music culture, zero investments from the country on arts and a super crowded market made possible by new technologies, so I’m not afraid of the continuous instability of the economic side of running a label. That’s what I like to do.

Great satisfactions also comes when you get unexpected acknowledgments from artists you admire, Julian Cope is a great fan of some of my records, especially Father Murphy and Mamuthones. But in general, seeing that a band you released is doing good, is approached by other labels, even bigger than BM, is always a good sign.

Nearly all of the artists you’ve worked with are Italian, and the vast majority of them are based in Italy as well. And this is a very diverse roster, I should add. Often it seems to me that Italians are very outward-looking, maybe even inclined to downplay their own country. Is part of your mission to share all this excellent music being produced in Italy with the world?

It is the mission. When I started I didn’t had in mind to release only Italian music, but that came pretty natural in the first years because I realized how many great musicians we have that weren’t released properly or that actually had an existing network of collaborators and fans outside Italy. Since then I decided to focus only on Italian artists, living anywhere, trying to spread the world around.

Italy has always been seen as pretty exotic when it come to music, but sometimes that’s because we ourselves have been outward looking as you mention. Especially the press. My inspiration comes from the great Constellation Records, who focused only on local musicians for a long time, serving high quality music with great looking packages to the world. That’s what I’m trying to do, promote underground gems outside the Italian borders and reassess the position Italian musicians have in the market.

Sometimes people forgets that Italy has forged some of the most famous experimental musicians in the seventies, that Italian prog music is renowned everywhere. As I always put it, with a bit of mordacity, we have Morricone and you don’t. Just in recent years, a term was coined and gained a bit of attention, about that Italian scene of musicians called Italian Occult Psychedelia. Many of the artists included on that scene are from the Boring Machines roster and all the others are friends I know, the music styles are sometimes very different but they all retain a red thread to an Italian heritage which comes from the experimental works of the past, whipped with today’s sounds and recalling the atmospheres of old Giallo films, horror and b-movies, Italian library music and much more.

You see, when I hear of Umberto (which I like) or I see all the reissues of horror movie soundtracks made by US and UK labels, and I feel they’re strictly an Italian thing, I get a bit sorry about all those Italians who seems to discover such sounds just now, like they never heard of the works of Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, all the Morricone soundtracks even for smaller movies, Egisto Macchi and a lot of other Italian musicians. If they don’t know this giants, how can I imagine they could get to know my artists?

And how has the scene changed in the last ten years in Italy?

Many of the artists I knew at the beginning of my adventure with the label are still making great music, despite the fact that live venues are dying on a daily basis, most of them still find a way to play live and the energy is very positive. Things haven’t changed much in the scene I’m regular with, it was very underground before, it’s very underground now, and always will be. It’s a niche that most of the times didn’t suffer of all the transformations of the indie scene, because those bands and labels always aimed to monetize, they called their things “products” and they followed the music industry rules, just with fewer money. The underground scene had nothing but its passion for music, its will to bring people together to listen.

I believe that the harder it gets to keep on, the stronger it will be, we are few people but fierce.

Lastly, tell us about the mix you’ve put together. And what can we expect from Boring Machines in the future?

This mix features tracks that spans all along the 10 years of the label, showing some of the states of mind I tried to represent with my releases, there are noisy tracks, more romantic ones. All of them are usually very long, so i had to do heavy edits, otherwise it would have last hours. I like long tracks, I’m a patient listener and I like artists who challenge the listener’s attention in an era of short Vines and emojis.

The future of Boring Machines is full of exciting things, for me at least. I just released a huge photographic box from Fabio Orsi with a tape of new music, two records are coming out in few days, 1997EV (post-apocalyptic psychedelia) and Passed (a ritual built on drum loops and otherwordly screams). During spring I will be releasing a new album from a trio comprised of Alberto Boccardi, Antonio Bertoni and Paolo Mongardi. Also, for the 10th year I have a small gift for all those who missed Death Surf from Heroin in Tahiti: it will be reprinted in a short run, because I can’t stand people trading it on Discogs for 50 euro, that’s ridiculous. Oh! And I have another big special planned: 4 LP will be released on Solstices and Equinoxes, only in 10 copies. There will be no information on artist names, no pictures, no digital previews, nothing. Just the records to buy with the number 10 on the sleeve. After ten years of spreading the best music around I ask people to trust my taste.

TRACKLIST

01.[2011] Luciano Maggiore & Francesco Brasini – Cham Achanes (edit)

02.[2009] Be Maledetto Now! – Tutti Quei Simulacri (edit)

03.[2008] Punck – Piallassa.mp3 (edit)

04.[2009] Claudio Rocchetti – Northern Exposure

05.[2012] HMWWAWCIAWCCW – For Nobody

06.[2009] Luminance Ratio – Like Little Garrisons Besieged (edit)

07.[2010] FaravelliRatti – Bows and Arrows

08.[2014] Maurizio Abate – Into the Void

09.[2012] Uggeri_Mauri_Giannico – 6.18AM Icy Leaves

10.[2016] 1997EV – DrySun Acid (short version)

11.[2014] Dream Weapon Ritual – untitled 1

12.[2015] Adamennon – Manvantara

13.[2015] Squadra Omega – Man’s Empire Ends At The Waterline

14.[2013] DuChamp – Gemini (tremolo mix)

15.[2013] Von Tesla – Null hypersurface

16.[2010] K11 & Philippe Petit – Residual Spookyness (edit)

17.[2011] Fabio Orsi – Loipe 01 (edit)

18.[2014] Zone Demersale – Politica Fondale

19.[2015] Paul Beauchamp – Pondfire

20.[2007] Be Invisible Now! – Super-K-82-83

21.[2015] Everest Magma – Nan Nan

22.[2016] Passed – Glory (I’ll show you light now) (edit)

Sonic Close-Ups: Milan

The work of Gianmarco del Re first came to our attention via Postcards from Italy, his excellent series of interviews reporting on the Italian experimental music scene for Fluid Radio. He contributed to our mix series with Un Paese Vuol Dire, what I described at the time as an exploration of “the concept of identity linked to that of place by focusing on sound recordings of areas in Italy affected by earthquakes, landslides and man-made environmental disasters, interspersed with music that explores space and meaning in other ways. He combines soundscapes, field-recordings, interviews, segments from TV programs, and even some music drawn from his personal collection of LPs from the ’50s to the ’70s.” Lately, Gianmarco has been producing Sonic Close-Ups, lovely audio-visual vignettes capturing the creative practice of a variety of musicians. Over a dozen have appeared thus far, including Rie Nakajima, Adam Asnan, Scanner, Enrico Malatesta, and Franz Rosati.

This latest installment, however, is really something quite different: an hour-long documentary of the scene in Milan. Milan is unquestionably the most active city for experimental music in Italy. Certainly the scene in Rome has been justifiably praised for its activities in recent years (see Italian Occult Psychedelia), revolving around venues such as Dal Verme in the Pigneto district, the Thalassa festival, No=Fi Recordings,Mai Mai Mai, Heroin in Tahiti, In Zaire, and much else besides. And I’d be remiss not to mention my beloved Naples, home to spots like l’Asilo and Perditempo, and artists such as Sec_, Aspec(t), and others. Around Italy you can find top-notch programming like the Flussi festival or hidden gems in small towns or tucked away in big cities.

But Milan is something else, something odd. It’s not on the coast, or near the coast, like so many other Italian cities, and it doesn’t even have a river. Sure, Leonardo da Vinci himself might have designed the city’s navigli (canals), but its just not the same. The city is flatter, its historic district surrounded by an uneasy a cosmopolitanism, Gothic and Renaissance churches surrounded by modern developments, tall glass and steel buildings. It is a city overrun by capital and fashion and big real-estate developers, but also centri sociali, anarchist squats, and a vibrant underground culture, consisting of dozens of artists, labels, distros, galleries, and a growing number of performance venues, often quite unconventionally so.

Watch Sonic Close-Ups – Milan below, or follow the link to read more about the city and its artists. Buon viaggio. (Joseph Sannicandro)

Sonic Close-Ups: Milan – Part 1 featuring Alberto Boccardi, Nicola Ratti, Attila Faravelli, Matteo Uggeri, Massimiliano Viel.

Sonic Close-Ups: Milan – Part 2 featuring Macao, Sara Serighelli – O’, Fabio Carboni – Die Schachtel, Standards, Lino Capra Vaccina, Haunter Records.

DISORIENTALISM

Many contemporary artists, in Italy and internationally, have taken inspiration from Italian music and soundtracks of the 1970s, the imagery of horror films, Spaghetti Westerns, and ethno-documentaries, and the occult rituals buried in the history of Catholicism, particularly from the south of Italy. Heroin in Tahiti, a duo from the Pignetto neighborhood in East Rome, best exemplify the blending of these influences, a genealogy explored in great detail in member Valerio Mattioli’s 2016 book Superonda, a “secret history of Italian music” between 1964 and 1976. [1]

Rediscovered music from this period (including prog rock, soundtracks from Italian genre films, Library music, minimalist and avant-garde composers, electronic music, early computer music, and free jazz groups) has emerged as a formative influence on a new generation of Italian musicians. For instance, those associated with the so-called “Italian occult psychedelia” (IOP) scene (a term coined by the Italian underground music magazine Blow Up in 2012), which seeks to portray the culture of “sun and violence” that makes up quotidian Italian life, just out of view of the throngs of tourists and postcard depictions of la dolce vita. [2]

The advent of peer-to- peer file sharing and the networked historiography of communities of mp3 blogs and fan sites, such as progarchives.com, allowed for discussion by lay-listeners and the cultivation of a broader audience for rediscovery. [3] The attention generated by such blogs has also helped generate an audience for such re-issues, both in Italy and internationally. [4]

The discourse of “rediscovery” is in a fact central aspect of this aesthetic, as IOP has been described as the Italian version of “hauntology,” a trend in contemporary culture that critics including Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds (borrowing the concept from Jacques Derrida, who played off the homophony of “hauntology” and “ontology” in French) have described as an inability to escape old social forms, the persistent re-use and transformation of the past as raw material for the present, a kind of nostalgia for futures which never materialized. [5] In this sense, we might better speak of rediscovery as an anarchaeology, a term developed by contemporary German media theorists inspired (not uncritically) by Michel Foucault’s genealogical approach to an “archaeology of knowledge.” Media anarchaeology thus differentiates itself from Foucault, embracing a non-linear approach to time that is not dehistoricizing, but capable of attending to both the political and technological effects of media synchronically. Rather than attempt to uncover a stable originary object, such scholars have developed an approach to media archaeology “in which both human and machinic agencies are articulated in specific media assemblages.” [6]

Music and sound present an alternative way into such studies of media, as sound is trans-medial in a way that other media are not, drawing our attention to industrial infrastructures and aesthetic dialogues that have tended to be ignored by other disciplines.

Contemporary Italian artists have drawn upon the rediscovery of earlier music and film as politically significant to the present, not in a conservative sense of pride in past accomplishments, but in order to deploy the affective connotations and political intensity of these references. The filoni (B-movies quickly and cheaply produced to exploit market attention generated by big budget foreign films) and psychedelic music of the 1960s and ‘70s are inextricably linked to the traumatic economic and political climate of those years. The anni di piombo or “Years of Lead,” so-called due to the prevalence of right- and left-wing armed struggle and decades of subsequent police repression, are inseparable from themes and affects which dominated the cultural expression of the period. “Italian occult psychedelia” thus channels and coincides with a general reactivation of the collective memory of this period, largely repressed following the media liberalization and intense consumerism inaugurated in the “Reflux” of the 1980s, closely associated with Silvio Berlusconi, a billionaire real-estate developer cum media mogul who served as Italy’s prime minister on and off between 1994 and 2011.

One might also point towards another recent academic discourse, made increasingly urgent by the ongoing refugee crisis, that of the “Black Mediterranean” (Mediterraneo nero). First developed by Alessandra Di Maio, [7] the concept draws inspiration from Paul Gilroy’s “Black Atlantic,” and Iain Chambers’ work on the post-colonial Mediterranean. Gilroy posits the Atlantic as a political and cultural space of multidirectional circulation defined by the Trans- Atlantic slave trade, an historical reality necessary to understanding both diasporic Black identities as well as Modernity itself. In work such as Mediterranean Crossings and Migrancy Culture Identity, Chambers applies a similar method to the study of the Mediterranean, demonstrating how music uniquely uproots and reroots geographies, how music is in fact paradigmatic of such multidirectional cultural flows.

And while the “Black Mediterranean” as a concept was coined only in 2012, the political and cultural manifestations it names have important precedents in the musical hybrids (rather than fusions) of the 1970s. Throughout this same period, the Italian academy has finally begun to grapple with post-colonial theory and take seriously its own colonial history (and present). The concept of the Black Mediterranean has slowly taken hold and encouraged a more dynamic understanding of the interplay and crosscurrents between and across the Mediterranean, as a space of circulation which both separates and unites. The term also serves as the organizing principle of a recent edited collection, The Black Mediterranean, which includes chapters from many of the leading academics inspired by post-colonial theory working in Italian studies today. [8]

This discourse also resonates strongly with duo Invernomuto’s musical project Black Med, which they have been developing since 2018, inspired by the insights introduced by Di Maio’s 2012 book on cosmopolitanism. Invernomuto began in 2003, to name the artistic collaboration between Simone Bertuzzi (b. 1983, who DJs under the moniker Palm Wine) and Simone Trabucchi (b. 1982), both of the northern city of Piacenza. Their work encompasses documentary film making, music, curation, publications, and performances. Black Med was developed as a workshop which has been presented at cultural institutions across Italy and the Mediterranean, as well as a series of curated musical mixes from DJs across the Mediterranean, streaming via their website. They’ve also expanded the study of the role played by music in this dynamic in other ways. For instance, in 2018 they brought Iain Chambers into conversation with Jace Clayton (an African-American writer and DJ known as dj/rupture) to discuss their shared theorization of the fluidity and circulation of modern music and its ability to “uproot.” [9]

More recently, they’ve curated Black Med, a collection of essays including work from Chambers, Di Maio, Mann Abu Taleb, Ayesha Hameed, and various other contributors with diverse voices and identities in relation to the Mediterranean. [10] This suggests the beginning of a direct dialogue between these two camps, the academic and the musical, in further elaborating the discourse of the Black Mediterranean. I aim to extend such a dialogue by developing the concept of disorientalism in order to analyze a particular current of music produced in Italy during the 1960s and, especially the 1970s. [11]

Footnotes

[1] Valerio Mattioli. Superonda: Storia segreta della musica italiana. 2015.

[2] Antonio Ciarletta. "Italian occult psychedelia," Blow Up Magazine, January 2012: 56.

[3] The Compact Disc (CD) boom of the 1990s was the first wave of this rediscovery, as the digitalization of music is the precondition of peer-to-peer file sharing. Even so, it is not uncommon on mp3 blogs to find direct from vinyl or tape rips of obscure music which had never been given a CD release.

[4] Italian film soundtracks and Library music have been of particular interest by crate digging hip-hop producers, who place special value on discovering obscure and unheard records to sample in their beats.

[5] Mark Fisher. “What Is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly 66, no. 1 (2012): 16–24. ; Simon Reynolds. Retromania: Pop Culture's Addiction to Its Own Past. New York: Faber and Faber, 2011.

[6] Michael Goddard. Guerrilla Networks: An Anarchaeology of 1970s Radical Media Ecologies. (Amsterdam: Amsterdam UP, 2018), 28. Goddard’s study of the “radical media archaeologies" of the 1970s, focuses predominantly on cinema and television, save for one chapter on pirate radio. Media anarchaeology is central to the book’s methodology. Goddard traces the term to Siegfried Zielinski, who in term had built upon the work of German Foucault scholar Rudi Visker.

[7] Alessandra Di Maio, “Mediterraneo nero. Le rotte dei migrant nel millennio globale.” La Citta’ cosmopolita. Altre narrazioni. Giulia de Spuches, e Vincezo Guarrasi, eds. (Palermo, G.B. Palumbi Editore, 2012).

[8] The Black Mediterranean: Bodies, Borders and Citizenship. Gabriele Proglio, Camilla Hawthorne, Ida Danewid, P. Khalil Saucier, Giuseppe Grimaldi, Angelica Pesarini, Timothy Raeymaekers, Giulia Grechi, and Vivian Gerrand, editors. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

[9] Jace Clayton. Uproot: Travels in 21st-Century Music and Digital Culture. New York: Farrar Straus and Giroux, 2016. Released in Italian as Remixing, viaggi nella musica del XXI secolo. Marco Bertoli, trad. (Torino: EDT, 2017).

[10] Invernomuto. Black Med. (Milano: Libro Humbolt, 2022).

[11] Cf. José Esteban Muñoz’s Disidentifications. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999).