Dear Listeners, It’s an off week and I’m still away from home. Since I don’t already have a 7” picked out for the next installment of Out of the Box, I thought I’d instead share an interview from the archives. For the previous installment of Out of the Box, I wrote about a split record from Yellow Swans and John Wiese. So without further ado, please enjoy with interview from late 2013 with Yellow Swan’s Pete Swanson.

Sound Propositions 05: Pete Swanson

Pete Swanson is perhaps best known as half of the pioneering American west coast Noise duo Yellow Swans, along with Gabriel Mindel Saloman. Yellow Swans disbanded in 2008, and Swanson kept a relatively low profile at first, self-releasing a few tapes and small-run LPs while the reputation of the defunct Swans continued to grow with the critically acclaimed posthumous Going Places (2010). Swanson re-emerged in late 2011 with Man With Potential, out on Type, a record met with near unanimous acclaim. Recently relocated to NYC for graduate studies, Swanson wasn’t expecting much from that record, and was unable to play many shows in support of it until his grueling school schedule let up. Though his set up hadn’t changed much since the late period Swans records, he had replaced his bandmate with a modular synth, and the incorporation of rhythms and low end beats found a welcome audience among those for whom Noise had become too codified and dance music too clean. Since then Swanson’s solo albums have continued in this vein, including the very dance floor centric Pro Style and more recent mini album Punk Authority, both strong representation of what to expect from his live shows and sharing a vocabulary with MWP. Swanson has also continued to collaborate with other artists, notably the slower more spacious jams of Beer Damage with Brian Sullivan (Mouthus) and the dense psychedelic guitar music of Sarin Gas, with Tom Carter (Charalambides).

His erstwhile Yellow Swans bandmate Saloman has recently released some records of his own, and the contrast between their solo work is telling: the score to a contemporary dance piece, an LP released by an art book publisher, a meditation on military drum lines. Whereas Saloman’s records post-YS have been sporadic, carefully constructed and conceptually rooted in art world discourse, Swanson has been much more prolific and rough-edged. A dedicated improviser, Swanson brings a coherence of process to his varied projects, despite varying set ups, gear, or instrumentation, working within the limits and finding what works best in each unique situation.

After being impressed by the athleticism and energy of his recent records, and reading about his gear and philosophy towards creating music, I was sure that Swanson would make an ideal subject for this series. And indeed, his approach is consistent with the values I’ve tried to highlight thus far. However, Pete and I don’t quite see things the same way, which produces some interesting tensions below, tensions that I think are worth exploring further. He is steadfast in pursuit of his craft, dedicated to the process itself. Recording live to stereo to maintain an urgency and coarse quality to his work, he openly disdains the pursuit of perfection, stating that it results in overwrought work that is alienated from its point of inspiration. This ethos seems to extend into his judgment of other media, as well as reflect something of his political standpoint, if only implicitly. Swanson’s form of improvisation relies on finding the balance between his own powers and the unexpected sounds being produced by his gear, in capturing the energy of the moment when the two strike balance.

In reviewing Pete Swanson in The Wire 335, Will Hutson sees in these albums the transition from “Noise Dude” into Sound Artist, but this belies the consistency of Swanson’s approach going all the way back to the early YS years. Maybe we can all do with a little less adolescent posturing, but Swanson, and noise more broadly, maintains an irreverence and anti-authoritarianism, a distrust of institutions claiming a monopoly on “correct” ways of doing things that might be worth hanging onto. And overall a sense of humor alongside the seriousness. Look no further than Swanson’s latest for a sterling example of these traits; Punk Authority, an ambiguous title that is both a criticism and an invocation.

In his recent book Japanoise, David Novak describes Noise in terms of scenes of liveness and deadness, which circulate in a feedback loop of performance and techno-mediated modes of listening. Thinking in these terms I can understand why, in our interview, Swanson insists that my wanting to keep performance and recording distinct ontologically represents a false dichotomy. The sheer volume and physicality of a Noise show ensures that the embodied aspect of sound is undeniable, the experience one that is highly individual and yet still social. But most of us find our way to those spaces through recordings, often listened to at home alone, although the process of finding and listening to music is itself deeply social, in terms of the establishment of communities of shared taste, authority, and circulation. Compared with, for example, the recordings of Giuseppe Ielasi (who is the subject of the next installment of this series), the typical Noise record is mastered at extremely high volume, leaving little sense of the ‘impossible spaces’ that are created on recordings such as Rhetorical Islands or Tools. Recording live to stereo means that everything has to find its place in the mix right in the moment, and each element comes to affect the others, literally as well as symbolically. As Swanson opens and closes the envelope on his kick drum or cymbal hits, melodic fragments of noise burst forth creating engaging patterns that are just one facet of the torrent of noise we are confronted with. The potential of each moment is pure affirmation of life, and as such the music conveys a celebratory quality that is often lacking in Noise music. It’s no wonder that the techno kids are moving their bodies to this, and it’s about time the pure veneer of club music got dirtied a bit. (Joseph Sannicandro)

You can listen to a SongDrop mix here featuring songs featuring Pete Swanson as well as artists that influenced him. [Unfortunately SongDrop is no longer active, but I’m leaving this in for posterity.]

At ACL we’ve been big fans of your recent solo output, and there are two things about that which sticks out to me. One is that it’s not about obsessive editing and layering but about live signal processing and mixing. So this approach, using a set up you’ve detailed pretty extensively elsewhere (here), the live mixing aspect, having everything channeled through a mixer and down to one thing, in the moment. Which leads me to the second aspect of your recent work, the combination of beats and rhythms into Noise music which it seems is becoming more common lately (Vatican Shadow, the Pan label, etc). That said, your approach lends itself to constant change. You’re in NY now. How has the pace and practices of everyday life that come with being in NY informed your music? Have the rhythms of the city impacted your music?

A few things regarding your above comments. Firstly, my approach to recording has been relatively constant. It’s not a new thing for me to be recording live to stereo and the vast majority of records I’ve been involved in have been produced this way. I’m generally not interested in music that strives for perfection. Control is such a boring pursuit.

I’ve really only made a few studio records and have found that process to be generally problematic. I’ve found that as the editing, mixing and general hemming and hawing progresses, the impact of the music your working on diminishes. That being said, I’ve just started working with an engineer on what may become the next album. This engineer is very familiar with my music and is willing to develop a unique approach to mixing my sound. Even one’s own working framework deserves to get blown up every once in awhile. It also might be time to reject the value of creating intense work and go for something more subversive.

Regarding New York, I’ve never been particularly drawn to the city. I’m a born and raised Oregonian. I love Oregon and wouldn’t be shocked if I die there. I moved to New York to attend grad school at Columbia and that is the sole reason why I moved. It was the only school I got into and I had no other options. I didn’t have much of a music career when I first jumped to NY and I was not interested in engaging with the music culture there very deeply. I wouldn’t say that I was disinterested, but I had, and continue to have, very serious demands placed on my time with my academic pursuits and those remain my priority in relation to anything artistic or social. My solo career took off about six months after I landed in New York and I was unable to do anything at all related to music for several months after it’s release because the first year of my program was so intense. The last two years of the program are slower and have allowed me to travel often, but I always have to be in New York to go to class and to see my patients. I rarely go to shows and don’t really consider myself to be part of any defined scene here. I have met a lot of great people in New York and I’ve found a ton of support for my work, but I still don’t feel like New York is my place and I intend on leaving in about a year, after I graduate. It’s very likely that I’ll end up in the middle of nowhere Oregon or California with a job and a small studio to send records out into the world every once in awhile.

I go hard pretty much wherever I live. New York is just more expensive and there’s more good art around here than in Portland.

You’ve said “there’s a serious push-pull relationship that occurs when musicians are improvising and I developed my setup to reflect that sort of relationship without involving another human. My gear pushes back and makes me make decisions I wouldn’t otherwise make” I think this is a good relationship to have with technology, thinking in terms of an agent with which you interact. An improv partner with whom you strike a kind of balance. With that in mind, can you talk a bit about your relationship to your TC-440?

Your timing is interesting. After touring with my reel to reel for about 13 years, I finally had a show where my traveling tape machine died and I couldn’t revive it. I set up for the show and the tape would just not advance. I still don’t know what’s up with it. It’s a pain to travel with one of these things and I have wanted to figure out a way around it for a long time and maybe I have. I just got a new pedal that will hopefully replace that beast.

The 440 has been an amazing piece of gear to have as a constant. It’s got a particular character that is unlike any other processing units I’ve used. It’s a home stereo grade Sony tape deck that can double as an analog stereo delay. For some reason, someone at Sony in the ‘70s decided it was a good idea to add a feedback level knob to this model and is one of only a few stereo tape delays that have ever been manufactured. I have a pile of these machines at my studio. I have five or six. I have one that’s in complete disrepair, one that works well and a few in varying states of disrepair. I can get all sort of melodic flutter, distortion and compression on top of the delay.. It sounds great with synth, guitar… really anything sounds good through it.

I usually will use the same reel of tape for a year or two. I like the sound of tape with crinkles and the gauzy effect of tape that’s been maxed out over and over again. I keep thinking about doing more tape-based recordings at some point, but it just hasn’t happened. I don’t have a lot of time and it seems like people want the techno-related stuff, so that’s what I’m messing around with. Maybe I’ll make that singer-songwriter album after I graduate.

I’ve heard you mention your early interest in the DIY punk/hardcore scene, which is also my own background. In my experience, many of us who are interested in this sort of music today, electro-acoustic music or music that in some way draws inspiration from avant-garde music as well as conceptual art, have a similar background of being interested in more extreme music (punk/hardcore, or industrial music). This genealogy seems relevant to me, as opposed to those who come from the EDM/club background, or who are more formally trained in the classical tradition. Can you maybe expand on this, how the ethic of the punk scene may have influenced your aesthetic, your attitude towards promoting concerts, releasing music, and your evolving material practice itself?

My history with punk has never come up as much as it has within the last year, as my presence in the electronic music world has become more established. In short, I’m a total outsider to this club world. I don’t work how people expect me to work, and I don’t really understand what or why these promoters are looking for. There have been so many awkward exchanges, but in the end people have generally been happy with my set and I’ve generally been happy about playing in this new context. The specific influences of punk are hard to unpack from all of these other things in my background that set me apart from techno producers. I’m not sure what comes from having teenage scuffles with skinheads, what’s from working with homeless people, what’s from being a macho American dude who played high school football, what’s from reading Andrea Dworkin and Noam Chompsky when I was in middle school… It’s hard to map out what is what.

That being said, I do think that my solo work and Yellow Swans logistically functioned in a way informed by my (and in the case of YS, Gabe’s) DIY background. I started booking shows when I was 14 because there was nothing in my town. This was 1993 and email wasn’t that common, so it was all by phone. Yellow Swans couldn’t play shows at clubs with nice PAs in Portland so we bought our own and kept investing in it. We would do long tours in cars and vans and we booked ourselves when we started. I can’t remember the last time I talked to a band that does proper US tours for two months in an Econoline. I don’t have to do that any more, and I couldn’t afford to do it time-wise or money-wise. When YS was hitting the road hard, we had to do it because we needed to cover our living expenses. I find that there’s desperation in American artists due to not having any sort of support from the government. You have to make it work somehow. From early on, I realized that YS had to be treated as a small business. We were a working band in so many ways and I still draw from lessons I learned in that band.

I find the term “extreme music” to be ridiculous as punk, noise, metal, etc are all highly established forms with their own orthodoxies. I don’t think any music or art is extreme. The term makes me think of some ripped dude flexing in front of some big speakers. I think becoming disillusioned with punk’s orthodoxies is probably more influential on my current work. I found the form of punk to be too rigid and wanted music that articulated opposition to forms I found problematic. The urge to hear this music came in the form of things like No Wave, Underground Resistance, early Mego releases. I grew to value uncompromised and confident amateurism, aesthetic dissonance, disorganization, flaw. This all lead me to noise. I saw potential in the vocabulary of electronic music, but I found, and still find, the ethic of dance music culture to be confusing and personally problematic. At the age I discovered electronic music, it didn’t do what I wanted it to do. It was made to serve a functional purpose as opposed to the violent catharsis that I really valued from punk shows. I still would rather be at a good punk show over a DJ night any day of the week.

The kick drum itself is such an incredible and powerful gesture to introduce. It can make the most chaotic sounds seem organized and part of the pleasure of working in the club context is getting people moving to absolutely destroyed garbage. I’ll literally have passages that will be nothing but white noise and kicks and people will be MOVING.

What I meant by extreme is more…abrasive. There are sounds that many listeners, those unaccustomed to it, might find abrasive. Often this abrasiveness does come from a place of opposition. Playing really fast, or playing really slow. Utilizing “non-musical” sounds. The world is decadent and ugly so I’m going to reflect that, or we’re surrounded by these (a)rhythms of industrial life so I’m going to make use of them, or I’m angry at my Dad so I’m going to play louder and faster, or whatever. That said there are aspects of your work, from Yellow Swans to present, that can be meditative, even soothing in a way, so I don’t mean to suggest that this body of work is at all monolithic. There are aspects of club culture that I do find really interesting, the fact that the audience is really central to the direction the music takes, the development of the genre happens in a different way because DJs are mixing a wide range of music into a semi-coherent narrative, always trying to stay current. Has your reception in more beat driven music scenes changed your outlook towards music and form at all?

I don’t see anything that I do as being extreme and have a fairly non-hierarchical approach to sound and it’s organization. Maybe that comes with my being interested almost exclusively in “extreme” music my entire life. I find much indie and pop music to be completely unbearable and find music by Mark Fell to be incredibly fun and engaging. It’s all a matter of perspective and I think discussing agnostic sound as being aligned with whatever personal associations we have with those sounds.

I was just at Incubate festival with some music writers and they had just seen Immortal play and were confused why anyone would want to sing in an unintelligible manner. I can’t even begin to understand why someone would even ask that question because I grew up pretty much only listening to rap and the Boredoms and grindcore. Singing rarely makes sense to me and isn’t any more valid than recording the sound of growling or screaming or whatever. Why would someone consider one voice sound more enjoyable than another? I like Horace Andy, Henri Chopin and Steve Heritage’s voices all in the same way, they sound good and convey meaning.

Is there any music worth listening to that isn’t in opposition to something in its context? I’m not sure that I can think of music that is innovative that isn’t acting in dialog against something going on in creative culture. I don’t think opposition has to be an aggressive thing at all, but I think that without opposition, you end up with the same thing over and over and over again. Meditative qualities, playing with boredom, space, melody 4/4 beats, can all be acts of opposition and have been really engaging tools in certain contexts.

I’m barely involved in club culture. I don’t find the act of DJing interesting, nor dancing in clubs. I don’t really care to actively engage in that culture any more than I don’t care to engage in any music culture. I’m just playing with these tropes right now and enjoying it. I find the music to be satisfying. I like being an outsider infiltrating that culture and don’t think I’d ever like to participate in it more than I am currently.

Ok, in regards to the bit about live vs studio; how do you view your recordings, then, if not as studio works? As documents of your live work at that moment? I mean, do you predominantly think of your musical practice as being something that exists in real-time?

In terms of actually performing the music, there’s no difference between live and recorded work. Everything is played and mixed in the moment. I’m much more concerned with improvisation than I am with composition and I feel like most recordings suffer as you get further and further from that original moment of inspiration.

There is considerable difference between what works live and what works on record so the main distinction between a live document vs. the recording is a matter of editing and the amount of extra care gone into cobbling together a coherent work to be listened to through whatever home system. There are decisions that work live that don’t work on record and I think a lot of dedicated improvisers refuse to acknowledge that difference. On the flip, many people who work more with composition aren’t as focused on the live craft and I think my having done a lot of improvising and live mixing allows me to produce work that sounds good without too much tweaking. I’ve always used playback as a means of informing my upcoming live shows. It’s a great tool to help develop an improvisational practice, which is very similar process to the transcripts I have to review for school from the therapy sessions I conduct so I can have better perspective on how I work with patients.

I don’t see my records as something that exists in real time, but I see the process of recording as being an extension of my live work and vice-versa.

For me, I think the two are quite different from an artistic perspective, they should be like theatre and cinema, but have been sort of kept back because we see records as documents of groups performing music that was written by a composer or composers. Recording is a studio art, performing live is a performance art. Obviously the practices are not unrelated and often there is a lot of overlap, but listening to a record is inherently a different experience than attending a concert. So for me there’s been a long process of unlearning, of realizing that recording can also be composing at the same time, tinkering with gear in the studio or editing samples or whatever, the work comes out of this studio process, one that isn’t by necessity a performative process. Rock in general has come to seem rather conservative to me, in that it sticks with a sort of understanding as recording being mimetic, even though it’s really not with overdubbing, autotune, mixing, having a producer, etc. Again, I don’t think any of these things necessitates ‘striving for perfection.’ A painter can cultivate a practice that doesn’t strive for perfection while still remaining a studio art. People coming from techno or hip hop scenes might not have the same distinctions. But there are aspects of rock that I learned from the punk/hardcore communities, the DIY shows and touring, the visceral quality of the music, the physical engagement of the audience…. I’m not asking for an accounting of all the ways that scene may have influenced you, I’m more interesting in the evolution of certain ethical and aesthetic concepts that seem to have run their course in rock proper but that still have room for growth. To do ’77 style punk today isn’t just retro, it’s really conservative and I think anathema to the spirit that birthed punk, as those folks were responding to their own context, there wasn’t something inherent value to the form itself. The values, maybe. Distrust of virtuosity, which encourages everyone to view themselves as a potential creator, to break down hierarchies. And I feel like music like yours is a more honest expression of those kinds of values than whatever may be happening in the rock scene today. But it also maintains a quality, that visceral quality, maybe an aggression, that you don’t find in the really slick electronic producers or the contemplative bedroom records that are a dime a dozen these days.

I think you present a false dichotomy between live and studio work. Some people use the studio as a tool for experimentation and feel most comfortable in that space. Others may feel more invested in live, phenomenological music. Yet other musicians will focus on composition as a means of exploring live and recorded work. I’m interested in working in a very streamlined way. I use gear that’s designed for a live context, for studio and even for home stereo. I’m not particularly interested in working with tools in any context that I can’t use live. I want everything to be integrated and part of the same process. I’m not interested in composition or production as being a primary part of my practice right now.

Additionally, I think there’s an inherent sense of perfectionism in recording work. There’s always a drive to control work during the production stage, even in my own work. I don’t think there’s any difference between any particular style of music in this regard or in regards to being valid or worthy of consideration. Electronic music, noise, etc are all just as garbage and codified as rock music and suffer from the same referential traps. Not to say that I’m above playing with reference, but I’m concerned with lifting ideas and transforming those references through corrosion, interruption, inappropriate context, etc.

’77 punk has always been conservative. The Clash will always be infinitely more boring than a band like Mars, who were able to apply punk ethic to their aesthetic content. They worked with songs and composition, but the results were totally in opposition to established structures. They were much more coherent in their vision than something like Stiff Little Fingers or something like that. I generally consider virtuosity to be a great burden that limits one’s ability to actually make good music. Ability compromises the clarity of a unique individual’s creative articulation. The more options one has, the more muddled their message becomes. I really enjoy working with constraints, which allows me fewer choices and saves a lot of time and consideration. It allows me greater certainty of action and generally produces better work than when I’m just freely messing around. Technical inability is a fantastic constraint.

When I speak of punk music that I grew up with, I’m referring more to what was going on in the 90s. Music like Bikini Kill, Unwound, powerviolence on Slap-A-Ham or Gravity Records skree. Music like Behead The Prophet No Lord Shall Live and Men’s Recovery Project are such unusual, forward-thinking bands and it’s unfortunate that there aren’t such forward thinking rock bands active these days… at least that I’m aware of. I particularly connected with the political alignment of a lot of these bands and the visceral and cathartic quality of the music, which I found more ecstatic and liberating than oppressive or angry.

I do think I draw a good deal from punk philosophy, but through the lens of a pragmatist. I’m very critical of idealism in all forms and prefer articulations of disorder to ones of order.

A different question might be how your practice changes when working with others, whether it be in Yellow Swans, with Tom Carter, with Brian Sullivan. Do you see such collaborations as a push and pull relationship, do you generally work from improvisation, set certain parameters that you then work within, is it totally open? Do you collaborate in real-time, or in sending tracks back and forth?

I’ve never been willing to collaborate remotely. It doesn’t work with my process and denies the social aspect of playing, which I think is essential. I always collaborate in an improvisational manner, but I also intentionally develop an approach to playing with the other person. Both Sarin Smoke and Beer Damage require specific instrumentation and processing. The music always evolves by pursuing points of consensus. They’re both musicians I respect a ton and enjoy their company so it’s fairly easy to reach agreements and enact changes. Each project is distinct and I think any listener could hear Beer Damage, Sarin Smoke, my solo work and understand that they were all different projects.

How do you feel about the rise of headphone culture? On one hand you’ve got records (and genres) made for solitary, bedroom listening, but you’ve also got the perpetually ipod culture, it’s bad for listening, for interacting.

I don’t really think one experience trumps the other. You are making me a little nostalgic for a room I had in Portland from 2002-2004 or so, where I had my bed in a wide closet, which served a functional purpose in providing complete darkness while I worked graveyard shifts at a program for developmentally disabled sex offenders, but it also transformed the room into being more of a lounge than anything. Tons of musicians in the neighborhood would drop by and we’d play each other records. I’ve always found the world of records to be extremely social. Headphones have their place as well. I think it’s amazing to be able to listen to a record privately and to be able to get into the details of the recording. I love being on the subway totally lost in a record. There’s so much to listen to and so many different ways to hear everything.

I’d also be interested if you could share some of the records that were influential in shaping your path, utilizing broader sound worlds, more open directions.

I’m such a fiend when it comes to seeking out new music that it’s hard to note a few specific records. My teen years were almost all punk/hardcore and hip hop. I did buy Boredoms “Super Roots” in 1993 on a whim after seeing some insane footage of them on MTV when they were on the Lollapalooza tour. That record definitely cracked my head open a bit.

I discovered Siltbreeze when I was 16 or 17 and got pretty deep into Dead C, but it was a slow burn thing. I had a copy of Tusk around for a few years and I’d keep coming back to it despite not really getting it. I continue to look to Dead C for inspiration in disorganization, collapse and fidelity. I’m not sure how anyone can do rock music better than these guys.

I moved to Portland after high school and fell in with a bunch of older, more knowledgeable musicians that turned me on to all sorts of stuff. I feel like there was one month when I was passed the entirety of catalogs of Majora, Lust/Unlust, Moikai, Mego.. I got schooled in post-punk and US and UK DIY punk records. It all happened quickly. So much of what I heard in this period is now well known, but was totally inaccessible to me in my small town Oregon hometown. Most significant from this era of listening were things like The Shadow Ring’s “City Lights” LP, Mark Stewart & The Maffia “Learning To Cope With Cowardice,” Main “Dry Stone Feed,” Mars “EP,” Pita “Get Out.”

I’m constantly finding new bits of sound to be interested in, but I find that I’m more influenced by my peers than I am by records currently. I feel like my music is more self-referential right now than it is engaged with other forms of music.

What works in other media resonate with your own aesthetics most?

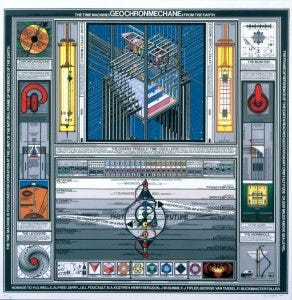

I have a general distaste for work that is overly aesthetically cohesive. I greatly prefer work that is densely layered and possibly self-contradicting. I was just at The Henry Museum in Seattle and spent time in a Paul Laffoley exhibit, as well as in a James Turrell installation. Both artists make work that I really enjoy and they’re both working from a large breadth of knowledge to create a highly unified, focused body of work. With that said, it should be apparent that I’m interested in the art world, but I don’t consider the sound, visual or textual elements of my releases to be directly inspired by this world, but rather the discourse surrounding artwork and the way artists talk about their work. It seems that the art world has its own critical shortfalls, but I greatly prefer it to the bulk of music journalism, which tends to focus on the entertainment value or social value of artists that are producing extremely mediocre work. Even people writing about more edgy sound work will focus on the language associated with the work or the visual signifiers as opposed to the content and vocabulary of the sound. I have always been concerned with sound first and everything else simply frames the sound, the less overt the visual gestures are and the more impenetrable the language is, the more the actual music gets written about.

I’m an avid reader as well and often use literary references in my track titles. I’ve referenced Paul Celan, Leonard Michaels, George Perec, Larry Brown, Amy Hempel. Right now I’m reading David Ohle “Motorman” and just finished up a few Rachel Kushner books. The last author I really got into was Cesar Aira, who seems to just crank out short novels that aren’t particularly labored over. His writing reminds me of improv musicians who focus on their larger practice and work from inspiration. I wouldn’t be shocked if he just writes each novel in a matter of a few days. It seems like he just decides what he wants to write about, writes it, then on to the next book. He will publish four or more books a year in Argentina.

It’s curious, now that you’ve made me think about it, I’d argue that in literary projects, or artistic projects in general, the process is what is valuable, not the result. And, nonetheless, I trouble myself with methodically erasing the traces of the process, making all notes and manuscripts disappear. Perhaps there’s no contradiction if the intention is for everything to be part of the process, including (and above all) the result, and for nothing to be there to distract from that.

I’m pleased you mention Cesar Aira. I actually just read An episode in the life of a landscape painter recently, and I can see how Aira’s practice might resonate with your own. If you’d care to expand upon that, that’d be great.

Oh. That’s the book of his that I’ve enjoyed the most. I honestly don’t know much about his practice other than he’s hugely prolific and incredibly creative. I have the impression that his work isn’t particularly labored over. I have the impression that he has a number of ideas for novels that he’s considering all of the time and just pounds out a novel in a short amount of time once he’s ready to write it. His writing doesn’t seem particularly labored over, but I feel like the larger trajectory of his writing involves his experiences writing informing each novel that follows. It seems like he’s invested in developing his process of writing as much as he’s invested in each individual novel. I like to think that he’s an improviser like Derek Bailey or someone comparable, only working with language and narrative.

An Episode in the Life of a Landscape Painter is such a great novel. It’s 80 pages of increasing hallucination and surreal content. The novel feels like the narrative is melting as it progresses.

Yeah, it’s a great read. In fact, you’re spot on. He has a steady routine, going to a café each day and slowly writing about a page in his notebook, with a special pen and in careful script. And then the next day he writes another page, without necessarily knowing where the work will end up. He claims he changes very little in the editing process. It gives his work a unique cadence and potential for surprise.

I’d also appreciate it if you can maybe talk a bit more about your set up. What do you have running through the Aux Send on your board? How’d you get into working with modular synths? Do you have more ideas than you can record, or do you find yourself altering your set up to create new ways of working? Do you approach a new project with a fixed idea or process to play around with, let the gear steer a bit, or something else altogether?

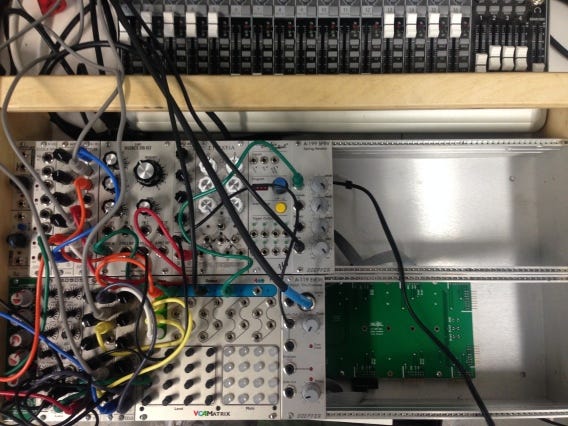

I started working with Modular synths in 2007, shortly before Yellow Swans ended. We had already agreed to stop playing and I wanted to find a technological replacement for a bandmate that was as unpredictable and fit within the musical process that I had been developing in YS. I didn’t really start using the synth seriously until around 2010, when I recorded Man With Potential.

Modulars make so much sense to me. I got into music through instruments and pedals and I love the tactile interface and the flexibility. I don’t really understand audio software and have never really got into it beyond understanding how to record live to a certain number of tracks. I’m not particularly partisan regarding analog vs. digital, but I really prefer the interface and immediacy of modular synthesis. There’s also self-contained constraints with the synthesizer, whereas software is much more flexible and therefore more problematic for me.

I’m constantly adding to my synthesizer and trading out modules. My processing system remains fairly constant. I have five different processing routes that I’m either running out of my mixer or out of my synth. I have two delays, an analog stereo delay through a Sony TC-440, which is home stereo gear and a Boss digital delay pedal, an old 3MS noise swash pedal that’s been modified significantly (but not with CV inputs like many synth dudes assume), a spring reverb tank and a low pass filter.

I’m interested in making a lot of different kinds of music and have no time to do it, so lately I’ve been focused on music that’s based around my synthesizer. I’m considering involving guitars and tape loops on my next record. I’d love to make an album of songs that are guitar based or do something much more abstract based on tapes, but I only have so much time right now so I’m more focused on techno related material right now. I’m not in a huge rush. I’ve been doing music for ages and will find time to make a lot of the records I want to make.

There’s always a lot of give and take in my work. I really only mix and make choices in the moment and the music that comes out is often very different than what I throw in. There’s a lot of give and take in between my actions and my gear. I’ll often throw modules into my synth that I’m not entirely familiar with and struggle with those on tour. I like throwing in new things so I have more to wrestle with. When I’m recording, I have often played with changing a few modules and effects while I’m doing the sessions to enhance the differentiation from piece to piece. I always like to let the gear steer. It usually knows what it needs to do.

And lastly, what do you have coming up down the line that we should look out for. Tours, releases, other projects….

Nothing is set in stone. Brian and I have a new Beer Damage LP that is pretty close to being done. I’ll be playing Unsound in October, some Northwestern US dates in December and some Euro dates in January. Beyond that, I don’t know. There’s so much that could happen, but it’s also possible nothing will. I have to juggle music and school. Music has to happen in it’s own time. I’ve been experimenting and recording a lot with the intention of working towards a new album, but I don’t think I’ve hit on the record I want to make just yet. Even if I make an album fairly quickly, It’ll be late 2014 before it can come out due to my school demands. Busy Busy.

Photographs courtesy of the artist. ACL would like to thank Pete Swanson for his thoughtful responses and willingness to participate in this series.