Dear Listeners, Joseph here. Today is the 100th birthday of el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz, born Malcolm Little, called Detroit Red, best known as Malcolm X (May 19, 1925 – February 21, 1965). The final minute of Matana Roberts’ 2015 album river run thee, the third installment in their COIN COIN series and the first solo installment, includes an excerpt from Malcolm X’s “Confronting White Oppression,” one of the few moments of text not spoken or sung by Roberts. That speech was made on February 14, 1965, almost exactly 50 years before the release of River Run Thee, and just one week before Malcolm was assassinated.

Roberts was featured on the podcast in 2024, at which time I sent out a Matana Roberts primer for paid subscribers. Today I am resharing an essay originally published in the Montreal journal dpi in 2015, exploring the third chapter of Roberts’ COIN COIN series, which was included as part of that primer. Thanks for Listening.

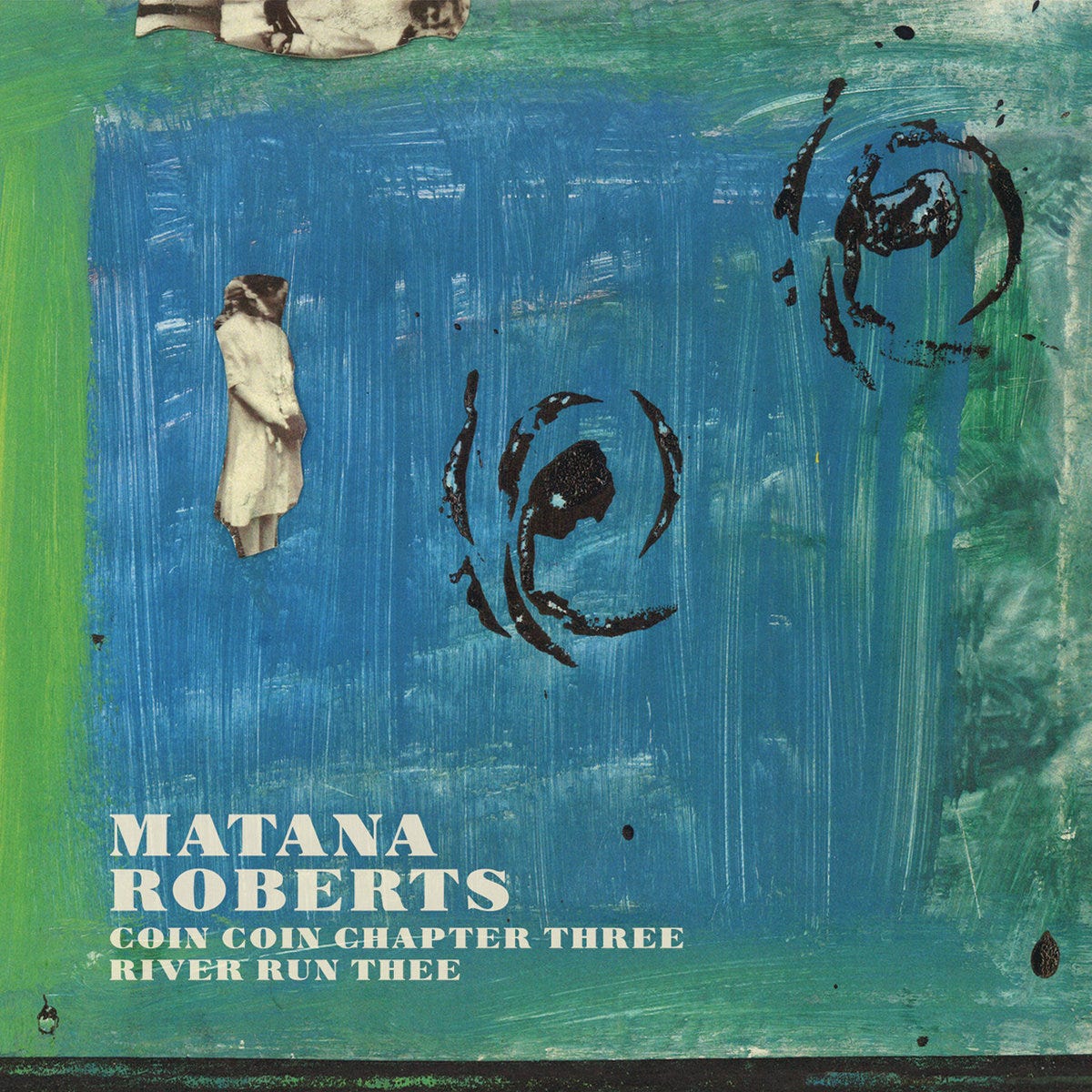

The Other Side of the COIN COIN: Matana Roberts’ River Run Thee

Fifty years after the assassination of Malcolm X, Matana Roberts mines their ancestry and the history of the Americas to produce a compelling and mournful counter-narrative that resonates deeply with contemporary struggles. Roberts’ latest album, River Run Thee, foregrounds the same collage aesthetic on display in their visual art. Perceptible in their earlier ensemble work for those who could listen beyond the jazz instrumentation, this third installment of their projected 12-chapter epic COIN COIN may finally help them transcend the inadequacies of the jazz label and refocus attention on the profundity of their message.

There is a general disconnect between a work’s political content its aesthetic form. This gap has not gone entirely unnoticed, and at various times in the last century or so artistic movements have attempted to harmonize their formal practice with their political commitments. Once a work has been commodified, however, audiences may connect with its formal aspects without contemplating or even being aware of any political dimension. Enzo Mari, a brilliant Italian designer and artist, put it well in criticizing the current vogue for mid-century modern design: “Rather than understanding its essentially ethical nature and trying to bring it to the next level, they copy the form.” Particularly after the Great War, artists turned against society, disenchanted. Many turned towards non-Western cultures for renewal, but in doing so reduced these cultures, “othering” their peoples in venerating them as “primitive.” The scholar Paul Gilroy advances a powerful counter-narrative to this view of Modernity in his influential book The Black Atlantic, re-inscribing the slave trade as Modernity’s founding moment. Rather than understanding black people as being outside of the Modern, Gilroy situates their cultures and struggles as foundational to Modernity.2 Kodwo Eshun’s poetic More Brilliant Than the Sun picks up on this thread in order to assess radical black music under the banner of afro-futurism, from Sun Ra to Drexciya.3

Matana Roberts’ work maintains a sense of ambiguity without falling into the violent erasure of abstraction. There is a multitudinous unity to their form, function, and ethos. The elements that make up each chapter of COIN COIN are not cannibalized or synthesized, but collaged – each constituent part allowed to be itself. Sometimes the ruptures between these elements are stark, other times they blend more subtly.

The experience of witnessing Roberts perform live is clarifying, especially compared with the more abstract political expression of most instrumental music. They remind us how the use of vocals and of shared tradition can be powerfully resonant. When, for example, they step on stage and performs “Bid Em In,” almost joyfully channeling a slave auctioneer describing young women for sale to potential bidders, one cannot help but be moved by the vulnerability and courage on display. This song creatively embodies the historical context of racialization, the slave trade and all that’s come after. Their commitment to socially engaged work continues, as exemplified by their recent premier of a new piece, “Black Lives Matter / All Lives Matter” at New York City’s Roulette on 3 December 2014. Still a work in progress, the piece draws parallels between the practice of improvisation and the work of social justice organizing. Roberts conducts the work through video and graphic scores based on imagery of Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, Tamir Rice, Eric Garner, and other victims of police or vigilante violence. The structure is based on grand jury testimony from these cases, as well as numerological elements related to Ferguson, Missouri.

As recent events continue to remind us, it is imperative that we attend to the structural causes of racism. To begin, we must ask why the ostensibly political avant-garde seeks abstraction often at the expense of committed social engagement. Musicologist Lloyd Whitesell’s critique of the early tape work of Steve Reich is instructive in this regard. Following Renato Poggioli and Matei Calinescu, Whitesell defines the cultural avant-garde as consisting of artists working in self-conscious opposition to traditional (bourgeois) values and institutions, and takes this stance further to argue that the cultural avant-garde has been marked by a rhetoric of negation since its inception. Whitesell traces this rhetoric of negation through music, poetry, literature, and the visual arts, showing how it results in a tendency of abstract formulations, a fascination with nothingness, and an unwillingness to relate the aesthetic to a historical or social context.4 Even John Cage’s famous concept of silence can function as a silencing, in so far as it closes off a certain relationship to sociality that in fact dictates the form of ‘experimentalism’ manifested by the avant-garde.5 Must pursuing abstraction and negation produce an unwillingness to relate the aesthetic to a historical or social context? Why and through what forces does Steve Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians” gain entry into the canon and not Julius Eastman’s “Evil N****r?”6

Roberts’ formation as an artist owes as much to the make-do DIY ethos of punk rock as it does to the spirit of the black avant-garde and free jazz. Born in Chicago, they came of age as a musician in the fertile hybrid music scenes of that city, benefiting from free music lessons in the American public school system. Through their political scientist father and his record collection, they were exposed to the music of the legendary AACM. As an adult they would later collaborate and for a time join AACM, mentored in particular by Fred Anderson. Their interests have always been varied, and they have continued to find means of channeling their myriad interests, be they intellectual, political, poetic, artistic or musical, into their present work, which is done a disservice to be described solely in musical terms. A seasoned writer and visual artist, producing DIY zines, working from a system of graphic and video scores of their own devise, their work insists on intersectionality and the totality of their activities inform their performances. In addition to physical zines, Roberts has also embraced, if perhaps at times skeptically, social media platforms such as Tumblr, creating real-time travel-logs of their #southernsojourn2014 and their current experiences living on a houseboat in southern Brooklyn.

Building upon the AACM credo “Great Black Music, Ancient to Future,” Roberts’ scope extends Black Music to an ostensibly universal audience who can benefit from black history and wisdom. In fact, their work demonstrates the ways in which this history is inseparable from American History as a whole. James Baldwin advised not only to “know whence you came” but made the radical (and pertinent) claim that acceptance and integration masked a deeper truth, advising his young nephew not to try to become like white people, but to accept them with love. “For these innocent people have no other hope. They are, in effect, still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.”7

COIN COIN is Matana Roberts magnum opus, a projected 12-chapter epic encompassing themes of history, ancestry and memory. River Run Thee is the third (and darkest) chapter, and first solo installment. As with the first two chapters, it was released by Montreal’s Constellation records, and at least another three installments have already been written and performed in some context. Often compared to large jazz ensembles like those of William Parker, Burnt Sugar, or Wadada Leo Smith, jazz is undoubtedly present in Roberts’ aesthetic as a composer and improviser, particularly in the way they play with tradition and evokes double consciousness. But ultimately it is inadequate and misleading, as their work transcends such labels and the emphasis critics have placed on the “jazz” parts of their work detracts from the uniqueness of their work.

COIN COIN evokes a plurality of meanings, and even its name demonstrates this radical ambiguity. Certainly the figure of Marie Thérèse ditte Coincoin looms large, a freed slave in pre-United States Louisiana who became a successful landowner and who has become an almost mythical figure. Coin is also evocative of money and of exchange, while simultaneously drawing on its French meaning to further emphasize intersectionality, evoking a corner. The first chapter, Gens de couleur libres, recorded with a large ensemble of Montreal free improvisers, told the story of Coincoin. Through an act of synchronic magic, the subject is blurred with the performer and the entire history between them, repeating “I am Coincoin/I am Matana” in a dramatic climax. Its follow up, Mississippi Moonchile, shifted the emphasis closer to Roberts’ family. Played by a tight sextet with jazz roots and operatic baritone vocals, it made extensive use of their idiosyncratic graphic scores. They call the technique “panoramic sound quilting,” which allows them to productively collage a variety of disparate styles improvised within certain compositional parameters. At once musical scores and visual art objects, they combine conventional and avant-garde musical notation and techniques with painting, vintage photographs and historical ephemera.

Quilting is a collective process, and Roberts’ sound quilting is no different. It is reasonable, therefore, to assume that a solo endeavor functions on a different register. And though that is certainly the case, the resulting album feels no less like a collective effort. An example from literature may help make my point clear. Each essay that makes up W.E.B. Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk begins with a lyric epigraph and accompanying bars of music, framing what comes after as more than just one man’s voice but a part of an ongoing conversation, a rearticulation of a message with the weight of traditions behind it.8 I sense a similar spirit at work here.

River Run Thee weaves together, quite literally, layers of field-recordings from the American South with improvised saxophone, electronics, and Roberts’ powerful ‘wordspeak’ evoking traditional songs and idle chatter. The bed of the album is a psychogeographic soundscape quilted together from a 25-day trip through the Mississippi, Louisiana and Tennessee. At times the result can feel claustrophobic, the shadow of a temporally shifting filigree moving across the entire history of the South. The field-recordings can be deceptively simple, with buried aspects slowly revealing themselves with repeat listens. One can never catch every detail, and certainly cannot tease out every hidden message, every connection, from every perspective. In the opening seconds the layers build rapidly, the sound of birds chirping and church bells ringing, voices humming, and Roberts muttering, almost inaudibly, “where the fuck is this place?” They answer their own question with what sounds like an invocation: “the South.” The bucolic scene becomes lost in a rising cacophony, gradually morphing into the screeching of a subway train in NYC. Their voice is mournful, echoing their saxophone blending into the backdrop of the drone. As the layers pile up, the saxophone riffs multiply, becoming busier, more chaotic; sometimes quoting traditional songs, other times responding to the field-recordings, while voices, Roberts’ voices, talk past one another. “Why do we try so hard? All is written in the cards.”

The words Roberts chooses to include in their compositions tend to be expository, or otherwise fragments of text or overheard speech. They are telling a story, but not always, necessarily, with the content of their words; just as often the narrative can be gleaned in the din of noise in which they are embedded, in the ambiguous zone between their cries and the wailing of their saxophone. To paraphrase the scholar Fred Moten—speaking about the album We Insist! by Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln and Oscar Brown Jr. but equally applicable here: “you cannot help but hear the echo of Coincoin’s scream, as it bears the whole of the story, redoubled and intensified by the mediation of years, recitations, auditions.”9

Despite its layered nature the album wasn’t the product of meticulous editing, but the result of a mostly live process of improvising and incorporating field-recordings and samples. The production, handled by Jerusalem in my Heart’s Radwan Ghazi Moumneh, plays an important role in the realisation of the album. Like a visual collage, there is no original to speak of. The work is only complete when it is finished and reproduced. Layering improvisations over one another maintains the feeling of collage, of rivers flowing into and over one another, and the result captures a unique hybrid of recording art and live energy. The use made of an early 20th century upright piano is indicative of the approach and what the production brings to the album. Rather than directly sound any notes, other aspects of the recordings were played in the room and recorded by a microphone placed inside the piano, acting as an acoustic resonant filter, granting those sounds some ghostly relation to the piano and its history without any evident timbral qualities. According to Roberts, they utilized cheap synthesizers not as sound sources but as effects, running the saxophone through them in order to manipulate their filters. The result gives even the most electronic elements of the recording a direct trace of human gesture.

The final minute of the River Run Thee features a short excerpt from a speech by Malcolm X, one of the few moments of text not spoken or sung by Roberts.

distinguished guests, brothers and sisters, ladies and gentlemen,

friends and enemies/

so I ask you to excuse my appearance. I don’t normally come out in front of people without a shirt and tie/

before I get involved with anything nowadays, I have to straighten out my own position, and/

which is clear, I am not a racist in any form whatsoever…

These words come from a speech known as “Confronting White Oppression” given on February 14, 1965, almost exactly 50 years before the release of River Run Thee, and just one week before Malcolm was assassinated. The reason the man had to apologize for his appearance was that his home in Queens was bombed the prior evening.

As far as endings go, it is a strong indication of how much work remains to be done, even half a century later. River Run Thee seems committed to confronting these challenges creatively. As the 10 minute opening song “All Is Written” reaches its bleakest moment, Roberts gives us an answer. “Why do we try so hard? Because we should.” This ethical imperative to struggle, for understanding and for justice, runs through Roberts’ oeuvre, form and content inherently intertwined.

LINKS

http://www.matanaroberts.com

http://iammatana.tumblr.com/

http://boatafloatbrooklyn.tumblr.com/

http://cstrecords.com/matana-roberts/

Bibliography

Baldwin, James. The Fire Next Time. New York: Vintage International, 1993 (1962).

Du Bois, W.E.B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: Dover Publications, 1994 (1903)

Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant Than The Sun. London: Quarter Books, 1997.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. New York: Verso, 1993.

Gopinath, Sumanth. in Sound Commitments: Avant-garde Music and the Sixties.

Adlington, Robert., ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Kahn, Douglas. Noise Water Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1999.

Letson, Daniel. “Designated: The Cynic/Romantic Genius of Enzo Mari.” Last modified: November 28, 2012.

Moten, Fred. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.

Weheliye, Alexander G. Phonographies: Grooves in Sonic Afro-Modernity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2005.

Whitesell, Lloyd. “White Noise: Race and Erasure in the Cultural Avant-Garde.”American Music, 19, 2 (Summer, 2001): 168-189

Notes

1 Quoted in Daniel Letson, “Designated: The Cynic/Romantic Genius of Enzo Mari.” Last modified: November 28, 2012.

2 Paul Gilroy. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. (New York: Verso, 1993.) Chapters 1 and 2.

3 Kodwo Eshun. More Brilliant Than The Sun. (London: Quarter Books, 1997.)

4 Lloyd Whitesell. “White Noise: Race and Erasure in the Cultural Avant-Garde” American Music, 19, 2 (Summer, 2001): 170-1.

5 Douglas Kahn. Noise Water Meat: A History of Sound in the Arts. (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1999.) 158-160.

6 “Music for 18” is performed dozens of times around the world each year in prestigious concert halls. Eastman died in poverty, his work rarely-if ever- performed until being rediscovered by Jace Clayton (aka DJ/rupture), whose 2013 album The Julius Eastman Memory Depot reintroduced his work to new audiences.

7 James Baldwin. The Fire Next Time. (New York: Vintage International, 1993/1962). 8.

8 W.E.B. Du Bois. The Souls of Black Folk. (New York: Dover Publications, 1994/1903)

9 Fred Moten. In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003.) 22.