I first encountered the name Luciano Berio as among those composers whom Steve Reich had studied with. I had yet to begin writing about Italian music (contemporary or otherwise), but that would change shortly after.

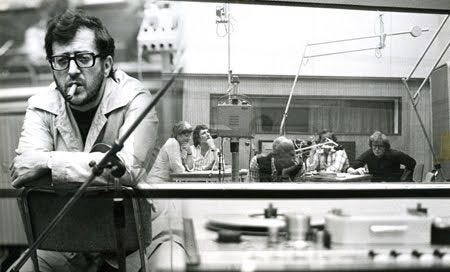

Many Italian composers, including Berio, Bruno Maderna, and Luigi Nono, began experimenting with electronics due to the establishment of RAI Milano’s Studio di fonologia in 1955. The studio also hosted numerous foreign composers, including John Cage, who spent considerable time there in 1958, where he recorded Fontana Mix with engineer Marino Zuccheri, and studied with Berio.

I came across Berio’s 1967 article “Commenti ai rock” during the course of researching my dissertation, and made the following translation for my own benefit, though I don’t recall if any quotes from it actually ended up in the final draft. [Indeed, I quote in at least one occasion from a footnote.]

So as I was thinking of additional material that readers of this newsletter might find interesting, I realized I had a number of translations that fit the bill. I’ve already shared a translation of Enrico Coniglio’s noWHere manifesto, and now here is my translation of this short essay by Berio. It’s far from a perfect translation, but I hope you will find some interest here.

Berio’s subject is ostensibly rock, and half of his essay concerns the Beatles, but he begins with a long consideration of Jelly Roll Morton and the influence of jazz on American, and thus global, culture.

Comments on Rock

Luciano Berio

One evening, many years ago (maybe 15), in the house of Roberto Leydi, I heard a series of quite rare recordings curated by Alan Lomax, in 1938, for the Library of Congress in Washington. In these recordings Jelly Roll Morton, the first great jazz pianist, recounts the story of jazz in his own way. I no longer had the opportunity to listen to those records but I continued to play them and adapt them in my memory. It is therefore possible, as also happens to the sonatas of Vinteuil, that “The distance or the haze leave only small parts visible.” [“la distance ou la brume ne laissant apercevoir que des faibles parties.”]

If I’m not mistaken, Jelly Roll Morton said on those records that jazz had come from Italy, playing a little of [Verdi’s] Il Trovatore’s “Miserere” and improvising a “hot” version; he also said that jazz had come from France, playing and transforming a quadrille; he said jazz had come from Spain, playing La Paloma, from Cuba, playing a tango, and from New Orleans. He concluded by saying that he had invented jazz. His business card in fact, next to his real name (Ferdinand Joseph La Menthe) bore: “creator of Blues, Jazz and Swing.”

It is not to be taken literally, of course; Jelly Roll Morton wanted to demonstrate, on the piano, that the jazz style could be applied to any type of melody while the rag was more restrictive and typical. What interests me, however, is that in that beautiful document Morton puts his finger on one of the most consistent aspects of American music: its composite character, its emphasis on performance, and its widespread yearning for history, for an identifiable genealogy perhaps to be found elsewhere in the world. It is certainly not insignificant that today even the rock phenomenon (the ingredients of which were mostly prepared in the hot cuisine of American popular music) needed an English group to explode: The Beatles.

America is a mysterious country. Things (including ideas and people) are thrown away when they no longer serve a specific purpose and when they cease to institute “habits of action.” The ideal model of unity, in America, is essentially of an economic nature, but money, it is well known, has a very short memory. This, it seems to me, is the reason why in a country so new, difficult, diversified, and untranslatable, popular music is more important and real than elsewhere and becomes one of the most significant tools of collective memory and universal consciousness. Like the music of societies that do not keep a written account of their past, American popular music has a highly iconic and gestural character. Within a socially defined frame of references, it tends to reflect and use specific modes of behavior and performance; that is, it seems to exhibit the characteristics of what it denotes. Jazz in particular is, among other things, a constant flow of citation from the blues; even when it is not chattering about Verdi and quadrilles (or later of Bach), it cites formalized behaviors: work behaviors, vocal behaviors, instrumental and bodily behaviors, playing styles, vocal inflections, motor habits, patterns on the instrument, etc. The jazz musician tends to reproduce things, whatever they are, in their own accent. We can see the jazz musician as E.H. Gombrich (Invention and Discovery, 1960) sees the painter who copies and who “will always tend to build the image based on the patterns he has learned to handle …. his manner and his motor habits will always come out.”

Precisely because of its representative and ritualizing nature of immediate reality, jazz has always aroused direct and immediate reactions in listeners. Rock (also called beat [bitt] in Italy, or, in France, yé-yé music) obviously sets in motion an analogous type of reaction today. However, there are some important differences between these two musical phenomena. I will briefly discuss them in their essential aspects, referring to rock (and some of the related phenomena) as it is now present in the United States (especially California) and England (especially on Beatles records). I am not aware of anything qualitatively and quantitatively analogous occurring on the continent. It is obvious that in the enormous amount of rock music produced today, only a small part is worthy of note.

While jazz (almost in a general sense) can be discussed in terms of distinctive formal properties, individual playing styles, class function and spirit of place, rock seems to me to be definable only in terms of general approach. It does not quote anecdotally and occasionally—on the basis of a syntactic coincidence—elements taken from elsewhere, but assumes a certain plurality of attitudes and procedures with a structural character, so to speak: the form of rock songs substantially changes depending on whether they refer to blues, charleston, western song, soul music, sea shanties, religious hymn, Elizabethan, Indian, Arabic music, etc. In rock, at least as a tendency, individual styles of execution are not noticed as much as group styles. Rock, often taken as a symbol of the “generation gap,” rapidly spread to all countries of mainly industrial development, subjected, in one way or another, to the direct influence of the American business empire. On April 15, 1967, in New York City, in the protest march against the Vietnam War, of about 350,000 people (most of them students), the only organized music was rock.

Although rock is partly based on the rock and roll of a decade ago, it cannot simply be considered a continuation with changes. Rock and roll, an offshoot of the Black blues, had its own rather uniform and rigid formal aspects. The same thing can be said of the currents of rhythm and blues and of soul music. Rock, however, represents an escape from the restrictive aspects of its stylistic lineages and a tribute to the liberating forces of eclecticism. The musical eclecticism that characterizes the phenomenology of rock is not a fragmentary impulse of imitation, it has nothing to do with the residues that have fallen into used and stereotyped forms – which are still identifiable as rock and roll. Rather, it is dictated by an impulse to inclusivity and with rather rudimentary musical means—to the integration of the (simplified) idea of a multiplicity of tradition. While jazz was rhythmically, metrically, harmonically, and phraseologically rather conventionalized (even today’s free jazz—too often reduced to a display of instrumental activism—is based on rather elementary syntactic schemes), in rock the conventionalized aspects are not strictly formal but mainly concern the acoustic nature of “lutherie.” “They have a different sound,” people belonging to different groups frequently say about each other, as the sound typology is the only constant that allows us to evaluate “linguistic” differences. With the exception of the beat, strong and often constant, all musical aspects seem open enough to allow for the inclusion of any possible influence and event. [1]

In its development and in its inevitable confrontations with a stronger culture (the culture of the white man: stronger, due to economic strength), jazz underwent a process of gradual acculturation. Jazz has paid an increasingly passive toll on the establishment. [2] Now jazz is a form of musical activity almost without ideology and without a recognizable relationship with social behavior.

The attempts at artificial fertilization between jazz and serious music [musica seria, as opposed to musica leggera, “light” or pop music] made a few years ago in America under the label of “Third Stream” were of a disconcerting stupidity.

Jazz is no longer danced, it is listened to on records, it is presented as a special event in the “Philharmonic Halls” or, when broadcast on the radio, it causes the kind of distracted listening theorized by W. Benjamin, which is clearly in conflict with the discursive and linear nature, in fact, of jazz (it is still a form of “accompanied melody”). This, not so much because the radio medium tends to level and mortify perception, but because in much of today’s jazz, between the characters of the melodic and harmonic articulation (usually very complex and discontinuous) and the metric and intensity characters (usually elementary and constant) there is an unresolved conflict. The same type of twelve-tone conflict, in which this conflict takes on a dramatic expressivity, that is, stylistic role. In the exposition of the theme of the Variations op. 31 by Schoenberg, for example, the characters of the instrumental roles and the distribution of density and the general contours of the expository gesture greatly overwhelm, in perception, the particular relationships between the notes and the supposed identity between the “horizontal” and “vertical” of the 12 sounds; the result, in short, is first of all the distorted gesture of an “accompanied melody.” For this reason, paradoxically, the exposition of the theme is perhaps the least demanding moment of the whole op. 31. It can be heard “casually”, that is, because the strong form is made up of an elementary opposition of density, an elementary gesture that reduces the rest, phenomenologically, to detail. Various aspects of rock prohibit “distracted listening”: it is inseparable from its conditions of use in a dance hall; its listening volume is necessarily very high; the vocal conception and the nature of the lyrics, in some respects, are new to popular music Virtually every person (young or old, man, woman or child, because they are sufficiently in tune and uninhibited) can use their voice in rock.

One of the most attractive aspects of rock vocality is in fact the naturalness, the spontaneity, and the multitude of vocal emissions. Most of the time the voice shouts, it’s true, but everyone shouts in their own way, without affectation. Even the lyrics, when not reduced to verbal “rituals”, nonsense, or instrumental onomatopoeia, are rarely stereotyped and are not very redundant (a certain redundancy is however provided by the iterative form of almost all rock songs). The effort sometimes required to understand the text and grasp its different levels of perceptibility is analogous to the effort required to decipher the message of a “psychedelic poster,” [3] (hallucinogenic poster—see color table) with which the programs and the hours of the ballroom are announced. The novelty and intrinsic nature of the sound of a rock group also prohibit the possibility of “distracted listening.” The recording of a piano always has a high degree of redundancy: the sound is familiar and therefore the experience and memory of the listener can complete the shortcomings of a faulty reproduction.

With the electronically manipulated sound of rock we have a situation quite similar to that of electronic music: if the fidelity of the reproduction is sacrificed, the content of the recording suffers disproportionately because what is lost cannot be compensated by the listener and is, in fact, irretrievably lost. Thus it happens that both rock and electronic music—both creatures of the radio and its mass machinery—are paradoxically incompatible with the means of diffusion that led to their development.

The distinctive characteristics of jazz—especially harmonics and meter—and the individuality of the playing styles were so strictly defined that they excluded everything that did not coincide with the conventional scheme.

Jazz could anecdotally quote those melodies that could fit within its syntactic framework. Il Trovatore, Carmen, the blues, Lucia, the Tango, the quadrille, the Paloma (often these were musical objects suggested by the performances of the Paris Opera), in the hands of Jelly Roll Morton and others, could receive a “hot” treatment (Bach semifreddo was the vogue a few years ago) with the use of “different, small variations—as Morton himself writes—and ideas designed to mask the melody.” Some of the main components of jazz can be traced, it is true, among the separate elements of rock; the emphasis placed on one or the other of these components or on how to combine them together can in fact characterize certain aspects of the style of execution of rock bands. [4] However, rock’s references to jazz do not seem to me to be the most interesting and characteristic aspects. Two important points of departure from jazz conventions are represented by the exceptional intensity of the sound of “hard” rock, especially when placed in its most appropriate context, the ballroom, and the inclusivity of rock. [5]

The stabbing sound intensity of rock is achieved with a great economy of means. The typical group consists of only four or five members: two or three electric guitars (including a bass guitar that has the same tuning as a double bass [in fourths, rather than fifths]), a drummer and a small electric organ. Sometimes a vocalist is added to the voices of the performers, singing with an everyday voice, without concern for emission. Voices and instruments are much amplified; a certain continuity of sound is obtained with a sufficiently controlled use of the feedback which also serves to level the differences in intensity between the various sound sources. Microphones, amplifiers, speakers become not only an extension of voices and instruments but become instruments themselves, sometimes overwhelming the acoustic qualities of the original sound sources. One of the most seductive aspects of the rock vocal style is, in fact, that there is none. The voices of the performers are magnified in all their naturalness and typicality, establishing with the formalized singing styles the same type of relationship that, in a film, the extreme close-up of a face establishes with a classic portrait.

Similarly, the inclusivity of rock is connected to the absence of a pre-established structure. [6] From this tendency to accept the reality of things-as-they-are, in different ways and attitudes, [7] derives a certain epic character of the best examples of rock. Each epic form is, among other things, also based on the revaluation and respectful transfer of “déjà vu” to another context. When instruments such as the trumpet, harpsichord, string quartet, straight flute, etc. are used with (or in place of) electric guitars (almost never the piano), they seem to take on the alienated character of a quotation from themselves.

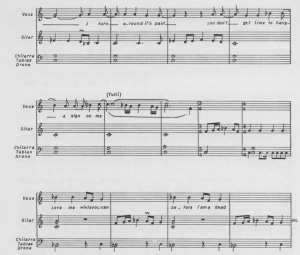

Harmony is essentially based on major and minor triads, plain and simple, without any interest in the mellifluous and sophisticated harmony of post-Gershiwinian cocktail lounges. Often, therefore, rock abandons the routine of I, IV and V chords, more or less encrusted with sevenths and ninths, in favor of third relations in the harmonic bass, which give an unmistakable Elizabethan flavor. Often, chord sequences with an “open” character are also heard: these chords, within certain limits, are interchangeable and their succession could be interrupted and restarted from any point (see example I).

Some pieces refer to Indian music, both instrumental (this is proved by the use of tablas, sitar and vibrato bar which, when applied to a normal electric guitar, makes its tuning oscillate in a controlled manner, thus simulating the typical inflection of the sitar) and through the adoption of a certain formal suspension and the adoption of certain scales. In “Love You To,” for example, the Beatles explicitly use one of the many Indian “modes” (see example II), developing, on a pedal (drone), two melodic lines almost irreducible to the conventional criteria of tonal harmony. The autonomous character of these lines sometimes produces a sense of peaceful plurality that has little in common with the usual song patterns. Even the rhythmic structure sometimes presents itself with quite unusual characteristics (especially in the context of 3,000 people dancing ecstatically): beats in 3/4 and 6/8 alternating with beats in 4/4, accelerandi and ritardandi; motifs of 5, 7 and 11 bars, passages of unpredictable length. In the drummer’s rhythmic patterns, the strong tempo of the beat is preferably not accentuated [as in the syncopated swing of jazz].

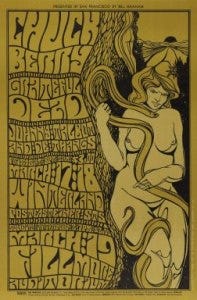

Finally, some pieces (especially the recorded ones) propose an overcoming of the very idea of song, developing a sort of sound dramaturgy made up of fragments of dialogue, montages, overlapping of different recordings and some electroacoustic manipulation: in these cases the form is collage. Those pieces by the Rolling Stones, the Tops, the Mothers of Invention, [8] the Grateful Dead and, above all, the Beatles, which are particularly linked to studio techniques are practically unplayable live. These manipulations, proposed for the first time by the Beatles, avoid sound effects and gimmicks: the surrealist appeal is obvious.

When a rock band uses other instruments besides guitars, drums and electric organ, it does so without too many compromises: the “extra” instruments are used as clean objects, as if they came from afar, in a way, after all, that suggests the utopia of the “return to origins.” The sound of the trumpet, for example, is always simple and naked, without deafness and without tricks, like in a painting by Grandma Moses: its sound is either baroque or that of the Salvation Army.

I am convinced that the “decadent” sound of a muted trumpet would be the signal that it is time for “Rock at the Philharmonic.” I sincerely hope that this moment does not come because it is clear that the meaning of this polymorphic “rock” revolution goes far beyond the songs that illustrate it.

NOTES

[1] This openness is typical of most of the hippie subculture (the American equivalent of the “Green Wave” [Onda Verde] in Italy and the Dutch “Provos”). For a hippie, authoritarianism, exclusivity, and interference with the affairs of others are anathema; the worst thing one can do is to bring down someone of his “chosen high” from “their high,” that is, from the effect of a hallucinogen. In the social sphere one encounters openness understood as tolerance, as a tendency to collage, to the collection of junk (someone commented once on the fact that there is nothing contradictory in wearing a “button for peace ” in the buttonhole of an Eisenhower-style military jacket; there is no contradiction because the jacket is taken as an object without history) and also as an integration of different elements and traditions.

[2] The history of jazz has also been the story of the white man who did his best to imitate the black man, and this is also true for rock and roll which was essentially black (blues) music with white imitators. Rock, on the other hand, has finally acquired its own autonomy, and as Ralph Gleason has pointed out, it is the black man who now has to decide whether to be part of it or not. When rock refers to black music, today, it is no longer an imitation; the blues has become one of the many tributaries that feed the river rock.

[3] Since every social movement is a movement “coming from …” and “towards …” the peculiarities of the hippie ethics are neither a spontaneously generated innovation, nor a blind reaction. The protest and evolving ethics of the hippies and their continental English counterpart are inevitably and dialectically characterized by the forces of their original society, no matter how much young people try to break away from them. While the attitude of the hippies is generally marked by a tendency to detachment (in contrast to the distinct politicization of the Provos, for example), their reaction to the sensitive world is ardent and they preach the baptism of total immersion. The young people of Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco or the Sunset Strip in Los Angeles grew up in a future-oriented society, driven by success, conditioned by the limitations of strictly defined experiences and with an eye always on the time to come; a society in which the use of the senses for something other than information gathering is viewed with suspicion. When he announces the events of the community he has chosen, the hippie then adapts art nouveau (making a bundle of all the hues, from Liberty, to Jugendstil, to Floral), to create posters and signs that do not have so much as their purpose to throw message of words into the passive brain of the housewives and dazed passers-by, as they do to seduce the viewer, inviting them to enter a labyrinth of colors and ambiguous lines. When he turns to chemicals, he rejects destructive “body drugs”, such as cocaine, tranquilizers, and alcohol, and instead turns to “drugs for the head,” looking for means that expand awareness of senses. He taunts the well-placed businessman who gulps down sips of scotch to “cheer himself up” (it is said that you don’t take LSD on a rainy day). When he speaks to the world for good he says “go slow, you move too fast, you have to make the moment last” (SIMON & GARFUNKEL), to listen to his music he goes to a place where he and his companions can immerse themselves in lights and sound and movement and “beat.”

[4] While one of the usual situations of jazz music was that of a certain group (or performer) who took the necessary material from an original reserve of songs and returned it in a very distinct style, in rock, the song and the style, composition, arrangement, and performance—even more than jazz—have become one. With a few exceptions, almost all rock songs today are written by or for a specific group, or they are the adaptation of characters from other musical languages. In other words, by identifying the levels of the song and the style, the group chooses its material not from a group of rock songs, performed by many groups, but from non-rock sources. Furthermore, while for jazz performers there was (and does) a tacit restriction on the plagiarism of playing styles, in rock the restriction concerns both song and style.

[5] Records and radio were the main means for the spread of rock. (The term “groovy,” roughly equivalent to “cool,” probably derives from groove—the groove of the record). The rock pieces that sold the most showed, for the most part, a certain fidelity to the more traditional forms of Western folklore rock and roll (commodious melodies, always intelligible lyrics and generally quite familiar musical patterns). These are the pieces that sell an astronomical amount of records, which are listened to by housewives (who constitute the largest part of the radio audience of the day) and, after school hours, by teenagers, the telephone requests of which determine the popularity indices. Despite this mass aspect that rock has in common with rock and roll, rock songs are generally better than previous songs: they usually exhibit more originality, more poetic sense, more genuineness, personal and social. The Beatles are an example of the happy combination of real qualities and constant popularity. There is one aspect of rock, however, which is firmly linked to live performance (which is more regional, has more select followers, and is musically more far out): it cannot be effectively presented on the radio because it is ‘inseparable from the experience of the “psychedelic dance-hall” (hallucinogenic dance hall) with its projections, strobe lights (the experience of strobe light is changing the style of dance and deserves a separate note), color, the undulating mass of bodies and, above all, the ergo-erasing beat, the sound, amplified to a level that becomes more visceral than auditory and that requires total submission or escape.

[6] It is the rejection of predetermination in general that distinguishes hippies. The precise nature of this segment of the younger generations varies greatly from nation to nation and within each country. There are great variations in the degree of politicization of the different communities, in the components of subversive rebellion, naive idealism, cynicism, in their mysticism and in their ethics of love. The visible sign, almost universally adopted, that distinguishes hippies, is the uncut hair. The start given by the Beatles, around 1962, acted as a precipitating factor in an over-saturated solution: they were followed by millions of young people. Long hair, as a sign of solidarity and belonging to a group, is almost ideal. The raw material is immediately available and the result is very visible; it is generally frowned upon by parents and its care requires a certain commitment (one cannot wear long hair only on weekends), and also gives those who wear them a certain air of nonchalance (after all, one cannot grow hair; they grow by themselves). Now, at least in the United States, long hair is assimilated to the point that it has become a fashion: even actors and 11-year-olds adopt them in slightly old-fashioned versions. Yet it has not yet lost its signal function: it always maintain some association with the attitudes and value patterns of hippies (an admirer of General Westmoreland would probably cut their hair very short).

It is not uncommon to see shoulder length hair in the hippie environment. This touches on one of the most sensitive dichotomies of our culture: male-female. Kindness, love, expansion of the senses are the keywords of the hippie society. The hippie male is committed to these ideals and bears all their signs without the need to prove his virility or his social position at all costs (those signs, in fact, actually place him outside the other society).

The religious connotations cannot be ignored and it is always a surprise to see Jesus walking down a San Francisco street … The old argument of conformism and non-conformism still holds the ground: hippies hope that their clothes and behavior express their life and interests and not the taboos of what they consider a moribund society.

[7] The term “freak” (meaning abnormal, strange, capricious) has taken an important place in the vernacular of the rock musician. “To freak freely” means improvising not in the sense of combining and reassembling given elements but in the sense of breaking boundaries , to find something new that can be worked out for the composition of a piece. Many rock bands avoid a “message”— in their songs—but they project a musical message that sounds like a manifesto of acceptance. What was previously technical imperfection, interference and disturbance, can become a valid sound element and be integrated into the musical action. (Typical examples are the sometimes hoarse and “swallowed” voices of the singers, who often sing in impervious textures for them and which seem to propose a new form—real—of vocal dramaturgy; or feedback, which can be used in surprising ways by an imaginative group. [MEV, GINC, AMM]) The idea of ”freaking”, therefore, is not simply that to produce anomalies to be used for their shock effect, but to move and push beyond the limits that define the form. The “hallucinogenic ideology”, in fact, is largely an ideology of acceptance and celebration of experience, which goes beyond conventional limits, be these perceptual, social, emotional or spiritual limits. This, however, does not happen in the spirit of pure rebellion, and appears to have a goal. The busy hippie uses strange sounds to enrich their idea of music, violates traditional costumes in an attempt to establish more meaningful human relationships, takes drugs in an attempt to increase their inner perception and widen the scope of their sensations and understanding, or to try to infuse everyday life with that special dignity that comes from the proper respect for small things and for the very fact of being in the world and not just passing into the world. But these, of course, are ideal terms of judgment: after all, “The Hippie,” as a pure form, is no more real than “The Italians” or “The Adults”. In this regard, it may be interesting to report a shred of reality. This is how a guitarist of the rock group “Grateful Dead” explains, in a private letter to L. Berio, the reason for that name:

… a protest implies, on the part of those who protest, a relationship with or against another thing. Rock musicians don’t seek this relationship, in fact, most of them deplore it. They don’t protest but celebrate, and this is the “purpose.” The unlimited celebration of things, to older people, more conservative and restricting, it must seem like a protest. And this is their reaction to what appears to them as the disintegration of the structure of their life. You too will become old and stubborn; and it will be the same for me. But there seems to be a death instinct flowing through hippie culture. “Grateful Dead” represents the propensity towards the dark and upside-down side of things. I don’t consider this destructive but I accept it in the same way I understand the emptying concept of Eastern thought. We let ourselves die and we allow ourselves to be reborn into something that is more than ourselves. Drugs —especially marijuana, but LSD in particular—allow us to quickly transform these concepts into lived experience. And when one sees beyond oneself, when the ego dies, one wants to express the wonder of all this and the gratitude one feels for being here. So: “Grateful Dead.”

[8] Especially among groups that enjoy regional rather than national notoriety, there is sometimes a tendency to delimit and specify their territory of musical action. This is not so much a question of style; the Beatles in fact, although they refer to a vast repertoire of idioms, from Chuck Berry’s rock and roll to Ravi Shankar’s raga, have a readily recognizable style. This fact probably contributes to establishing a sense of camaraderie and mutual admiration among the groups. However, there are even more significant facts, an atmosphere of generosity and contempt for the money society, which pervades the hippie scene. Ballrooms, for example, are big business, with all the rivalry, brutal bargaining, and aggression typical of “big business.” When a member of a rock band was asked what his position was in relation to all this he replied: “I leave it in the hands of the impresarios. How can one find the time to be a beautiful person (ethically) if one gets involved in these matters?” One group, in fact, “The Loading Zone,” has completely given up on the financial aspects of its musical activity. Thanks to the substances of one of the members they play for free.

Susan Oyama

[Berio’s second wife, from 1966-72, a noted philosopher of science]

Originally published as “Commenti al Rock,” in Nuova Rivista Musicale Italiana (May/June 1967)