IN MEMORIAM

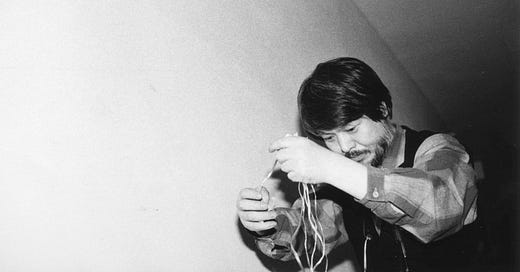

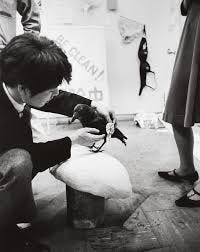

This post collects reflections, music, and writing about pioneering artist Yasunao Tone, who died on 12 May 2025. Born in Japan in 1935, Tone was untrained in music and was empowered by the experience of improvising along with fellow students including classmate Takehisa Kosugi at university in the late 1950s, a meeting that David Toop details in his book Into the Maelstrom. Tone became associated with Group Ongaku, and later Fluxus. He relocated to the United States in 1972, where he built a distinguished career as a musician, performer, and writer, working alongside the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, Florian Hecker, Russell Haswell, and many others. Recognized as a key figure in the development of Glitch music, Tone gained acclaim for his radical reworking of compact discs and CD players, pushing the boundaries of digital sound. At least, that was my introduction to this work. His Solo for Wounded CD (released on Tzadik in 1997) made a big impression on me when I first heard it in the early 2000s. The material below presents a much less reductive portrait of a singular artist and thinker.

In the introduction to Yasunao Tone : Noise Media Language (2007), the [very much still with us] Achim Wollscheid writes that “what’s so striking about Yasunao Tone’s work is that it is both free and hermetic – because it has no reference. It’s not presenting, it is present. It is not made to tell you something. It is not something. It just is.”

Noise Media Language was released as a book and accompanying CD by Brandon LaBelle’s Errant Bodies. It’s worth tracking down the physical, but the PDF is available to read here. The book contains a number of enlightening essays, photographs, and other documentation of significant projects. Contributors include Robert Ashley, Dasha Dekleva, Federico Marulanda, and Hans Ulrich Obrist. In particular, I’d like to share the conclusion of William A. Marotti’s “Sounding the Everyday: the Music group1 and Yasunao Tone’s early work.”

Tone is one of a number of artists in Japan and elsewhere who, in the 1960s, working across forms and genres, created a kind of investigative art practice and innovative aesthetic oppositionality. While his work also remains ground-breaking as art and music, returning to Tone’s route into artistic performance reveals his distinctive contribution to an insurgent avant-garde. The issues such work raises not only add to our understanding of the particular politics of culture in Japan in the 1960s, but also open out onto the global stage, illuminating aspects of the 1960s as a global moment. Like many of his contemporaries, Tone drew upon historical and current avant-garde theory and practice (including both Euro-American and domestic work) and enlivened it within a specific Japanese context. His work demonstrates how the artistic and political are inseparably bound, especially in moments of crisis. If one of the products of his early experimentation has been a long, fruitful, and distinguished career as an artist, performer, and critic, we can also appreciate its particular origins: Tone’s distinct route into the broader forms of artistic and political action of the global 1960s.

The tributes have been rolling in, but the most concise comes from New York’s Blank Forms:

The only 80 year old I've been to Berghain with AND who thinks Autechre is "too commercial."

The following email which Blank Forms sent out to subscribers nicely encapsulates Tone’s life and practice.

Yasunao Tone (1935–2025)

Conceptual artist, composer, and author Yasunao Tone passed away yesterday evening at the age of 90 at Presbyterian Downtown Hospital in New York, due to a series of age-related complications. An outstanding figure among his peers, Tone is best known for what he calls 'paramedia art', through which the telos of a given technological product is deviated from in order to open up a new and indeterminate creative space.

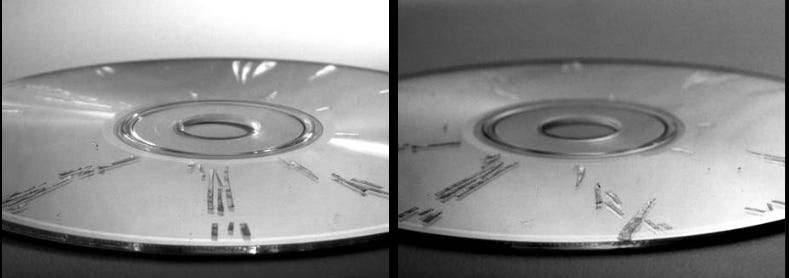

Tone was born in Tokyo in 1935 and graduated from Chiba University in 1957 with a degree in Japanese literature. Early in his career, he began writing and publishing art history and criticism. In 1960, he became an original member of Group Ongaku with Takehisa Kosugi, Shukou Mizuno, and others participating in what is considered the world’s first freely improvising music ensemble. By 1962, he was a founding member of the Japanese branch of Fluxus, composing event scores, pioneering sound installations, and participating in numerous happenings. He was also an active organizer, contributing to the social interventions of the Hi-Red Center and the computer-based art of Team Random. In 1972, Tone moved to the United States where he composed numerous scores for the Merce Cunningham Dance Company and began experimenting with the applying ideas from automatic writing, action painting, and the readymade to sound and experimenting with the transliteration of text into music via images with analog and digital means. His 1997 piece "Solo For Wounded CD" is the recorded culmination of a paramedia tactic dating back to 1984, in which he plays CDs prepared with pinholes and adhesive tape, de-controlling their devices' playback to skip and randomly select fragments from a set of sound materials.

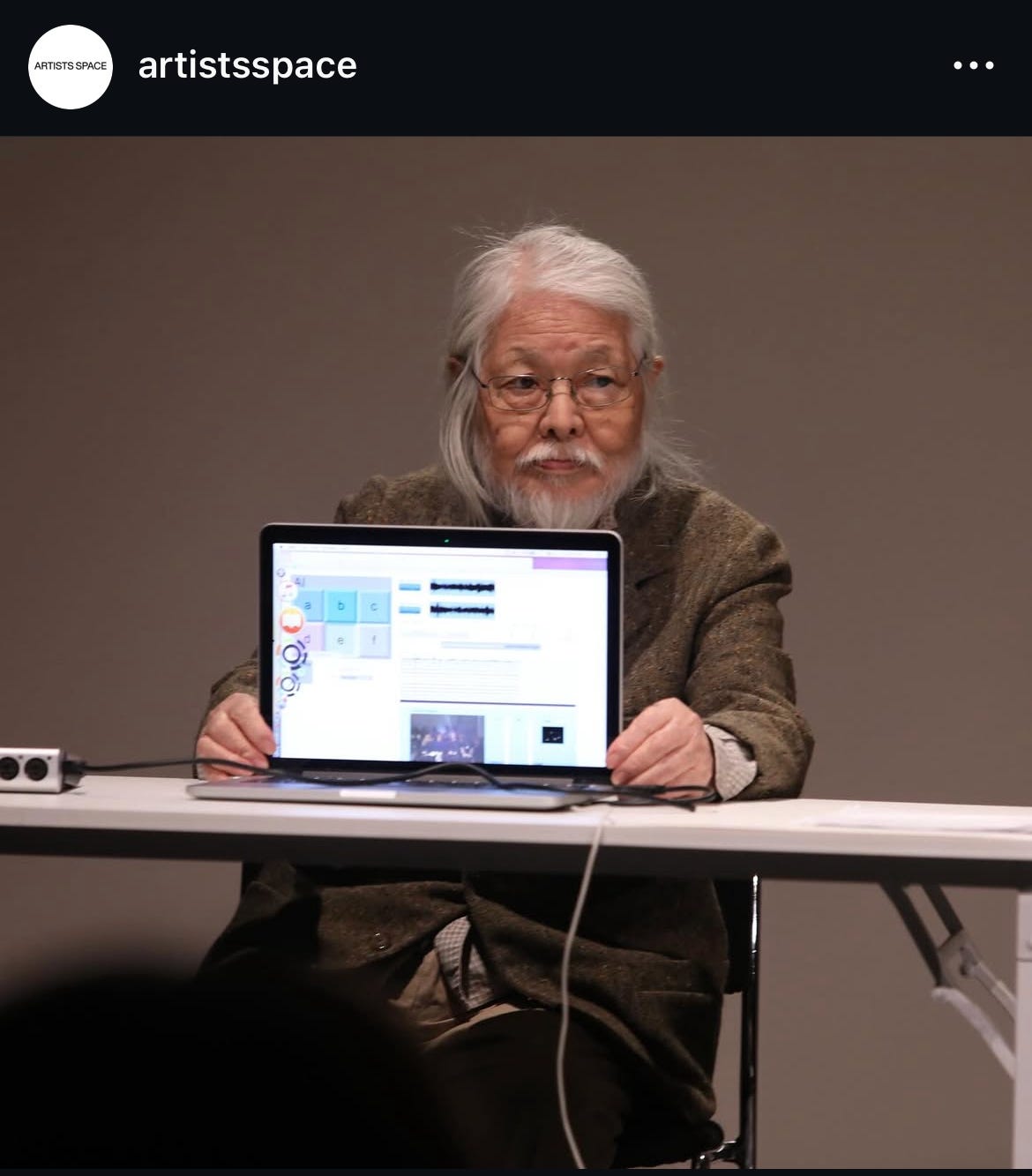

Often regarded as a predecessor to the glitch music of the 1990s, Tone’s pioneering approach extended beyond early digital experimentation. In later years, he turned his attention to the inner workings of digital file formats, developing a series of works known as MP3 Deviations. These pieces deconstructed and manipulated the structure of MP3s, serving as the foundation for more recent experiments involving artificial intelligence. Tone was a restless innovator who consistently sought out new collaborations with the next generation of artists, pushing his work in new directions decade after decade through his collaborations with composers such as Russell Haswell, Florian Hecker, Rhodri Davies and Mark Fell. His work has been presented at major institutions across Europe, Asia, and the United States, and was the subject of a career retrospective at Artists Space in 2023.

A part of the New York City art and music scenes since the 1970s, Tone has been an important collaborator, working with many practitioners and in many contexts over the last decades. His creative contributions, energetic presence, and powerful work will continue to resonate into the future. He will be greatly missed.

Tone arrived in New York in 1972, the same year that Artists Space opened at 155 Wooster Street in SoHo, a transitional moment for the neighborhood’s post-industrial transition, as the post-minimalist generation of artists pioneered new means of working together, alongside the burgeoning loft scene which allowed jazz musicians, artists, and others to commingle and present unconventional works and actions. Artist Space has gone on to become an important non-profit art gallery and arts organization. In the post below, they reflect on their collaborations.

The Kitchen, another of New York’s most important remaining art spaces that has always included experimental music and sound in their programming, reflected upon their long relationship with Tone, sharing some archival images.

The following passage from Seth Kim-Cohen’s In the Blink of an Ear (2009), helps to further situate Tone art historically.

Examples of the exchange from the visual to the sonic and back again are everywhere apparent since the 1960s. From Cage’s New School class emerges Fluxus and Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings.” Following these innovations, a relational-performative conceptualism becomes evident in works such as Nauman’s violin pieces, Vito Acconci’s Following Piece (1969), Adrian Piper’s Catalysis performances (1970), and Dan Graham’s Performer/Audience/ Mirror (1975). An argument could be made that the performance and relational branch of conceptual art is a direct descendent of Cage’s influence on visual arts practitioners. But this two-way ferment was not restricted to Cage’s influence, or to North American arts. In Tokyo in 1960, the future Fluxus members Takehisa Kosugi and Chieko “Mieko” Shiomi, along with the media-art pioneer Yasunao Tone, formed Group Ongaku (Music Group), made up of art students and musicology students at Tokyo National University. Group Ongaku stumbled upon what Tone described as “an absolutely new music. It was an improvisational work of musique concrète done collectively.” In 1963 the South Korean Nam June Paik presented his “prepared television” works in his Exposition of Music—Electronic Television at the Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal, Germany. Starting in 1962, the Vienna Actionists (Günter Brus, Otto Mühl, Hermann Nitsch, and Rudolf Schwarzkogler)—members of the first generation of Austrians born during or after the war—engaged in an aggressive, often violent confrontation with the conventions of art, performance, music, and society. (214)

Throughout “Into the Hot,” chapter 6 of Into the Maelstrom (2016), David Toop provides a valuable synthesis of post-war Japanese avant-garde music, including many interview quotes from Tone that provide important context and color. This chapter also includes an analysis of Tone’s 1960 essay “Improvisation As Automatism” and development as an improvisor.

For Tone the barrier to achieving their ideal of improvisation was melody. He would play as many notes as possible on the saxophone or leave spaces in short passages, yet still not overcome the problem. His next step was to play many different instruments from the ethnomusicology department, all of them in quick succession. From the university the group shifted their sessions to Mizuno’s home where they attempted collective improvisation of musique concrète by making sound on everyday objects.

In 1970, artist, composer and cultural commentator Yasunao Tone ventured a more positive interpretation: ‘The work is always unfinished, fostering the idea that it is equivalent to the everyday, to real objects and daily activities. Thus it’s not at all strange that every concrete object or ordinary action suffices as a painting.’

In Background Noise: Perspectives on Sound Art, Brandon LaBelle considers the work of Yasunao Tone alongside that of Bill Fontana and WrK to theorize the relationality of sound through case studies of their differing uses of site specificity. Tone gets an entire chapter dedicated to his work, “Language Games: Yasunao Tone and the Mechanics of Information”

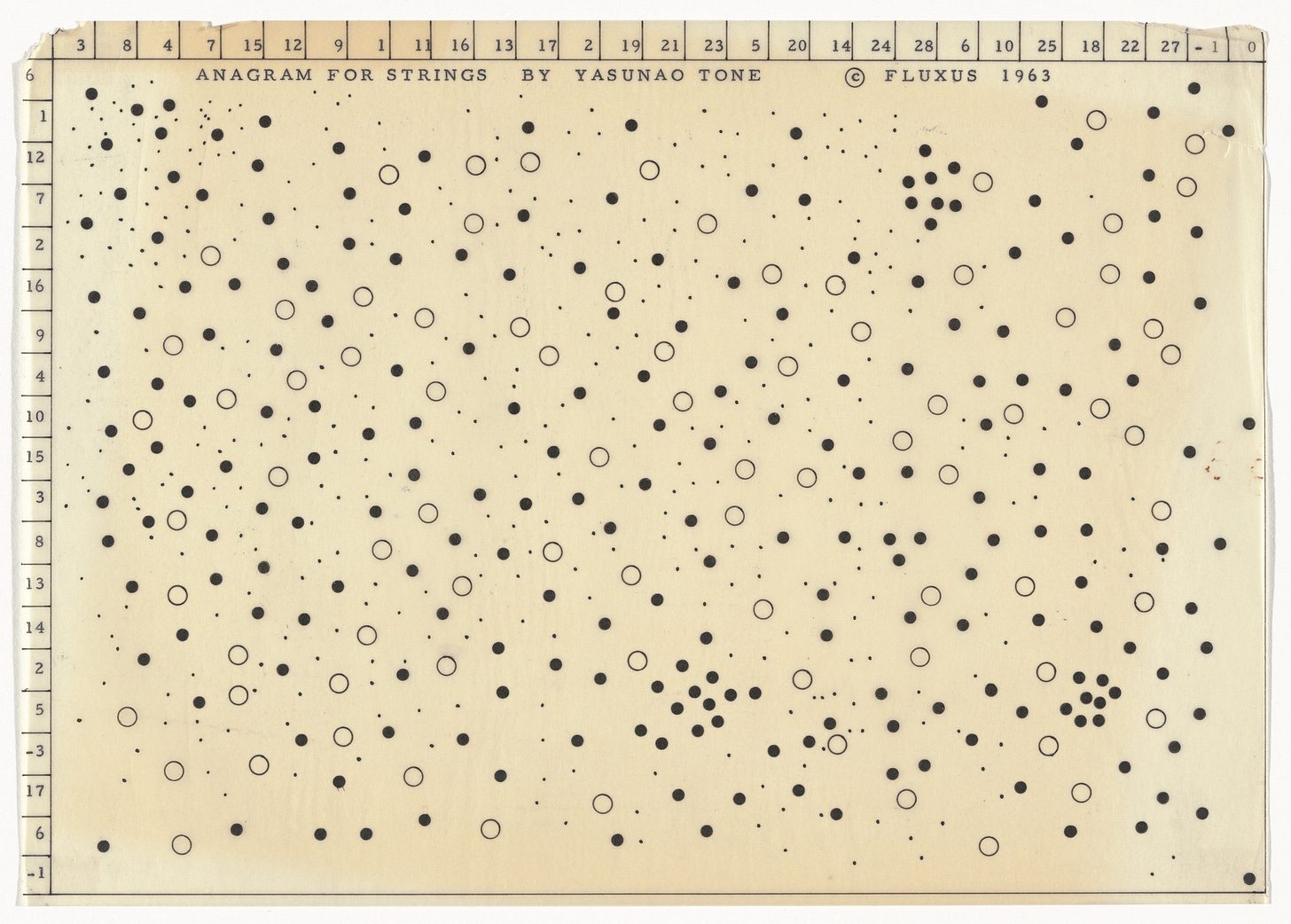

Soundscape work tries to be honest to a given location and what is found there, to reveal the path toward an inner journey, without labyrinths or tricks. In doing so, though, it may in the end overlook its own contradictions and their productive potential: that is to say, the alien relation, the displacement, and the difference may be utilized as operative terms in making work, as labyrinthine journeys that immerse a listener not so much within a plenitude of poetics but within a system of confrontation: where sound’s absence may speak. The artist Yasunao Tone explores such strategies by implementing difference and discrepancy, noise and its features, as makers of meaning. Tone’s work charts the peripheries of meaning by introducing noise into the equation. Whereas soundscape work aims to minimize “translation” so as to get at the real, Tone embraces translation as an overall strategy. Such interest appears throughout his career, from early projects and compositions employing graphic notation that lend to stimulating an array of interpretive results, as in his work Anagram for Strings (1962), to later works, such as Molecular Music (1983), based on translating or transmuting live projected images into sonic events. For Tone, forms of mutating one piece of information or material into another articulates a greater impulse or imperative to transgress the hierarchical structures by which meaning operates. Converting image or text or code into a systematic progression of noise, Tone undermines the ability for meaning to arrest the very material output of his own work, to piece back together the shattered form. Tone’s “interest is not in disclosing, but in exhausting” the residual outcome by continually countering the move toward recuperated meaning.With his more recent work, translation is cultivated so as to arrive at increasingly diverse forms of noise. (218)

Over at the Wire, Alan Licht’s 2002 interview with Tone is currently free to read. Here’s a choice passage:

The digital era ...brought Tone into recording for the first time. Previously, he says, "I was not satisfied with recording because it presupposes to repeat the same sound over and over." Indeed, pieces like Molecular Music (1982-85), in which oscillators were controlled by films and light sensors on screen, had been constructed in a way that they would never sound the same way twice. He had long considered his pieces unrecordable. "In a performances the audience in the front rows can hear the contrast between amplified and unamplified sound," he claims. "In a recording that disapears. It's also more spatial, and you can't reproduce that in a record--maybe if you sit in the center [between the speakers] in one position. [In the 80s] a producer for Nonesuch offered to have my pieces recorded, and I told him that's very good, but if I think about it, for my pieces, there would be too much lost. I turned him down." However, Thomas Buckner of Lovely Music offered to release a CD in 1992, and Tone found a way to use the medium to his satisfaction.

Here Tone is echoing John Cage, who also claimed that records “destroy one’s need for real music . . . [and] make people think that they’re engaging in a musical activity when they’re actually not.” (Yasunao Tone’s “John Cage and Recording,” [Leonardo Music Journal 13 (2003), 11.) But part of what makes Tone’s legacy so significant is that, already a historical artists, he produced an entire career’s worth of innovation after beginning to work with recordings.

Marie Thompson’s excellent study, Beyond Unwanted Sound Noise, Affect and Aesthetic Moralism (2017) reassesses Tone’s work, in contrast to and in dialogue with work by Christian Marclay and Maria Chavez. First, he appears in her introduction, as she sets up her intervention, re-reading the concept of noise through the lens of affect theory:

The decentring of noise’s listening subject does not result in an evasion of ‘traditionally’ human questions concerning the ethical, the political and the cultural – as will become clear, these questions inform and underline noise’s manifestations and effects. However, in recognizing that noise goes beyond the listening subject, this approach enables the development of connections between noise’s audible manifestations that affect individual and collectives of listening subjects and its other, largely imperceptible manifestations that affect non-human bodies and relations. Indeed, noise’s affectivity – its capacity to modulate, perturb and transform – is understood to underline both an encounter with disruptive neighbours and the stuttering outbursts of Yasunao Tone’s ‘wounded’ CDs. Hence, an affective approach to noise that no longer relies upon a constitutive listening subject helps to draw together noise’s social, informational and artistic manifestations. (7)

Tone reappears in Part Two of the book, “The parasite and its milieu: Noise, materiality, affectivity,” in which he considers his digital manipulation in contrast to the way other avant-garde artists has repurposed vinyl records.

While Marclay and Chavez explore the potentials of an ‘outmoded’ medium that is already obviously noisy to contemporary ears, Yasunao Tone’s experimentations with compact discs used – and ‘abused’ –state-of-the-art technology. Formerly an active member of the Tokyo Fluxus movement and the free improvisation collective Group Ongaku, Tone began to experiment with CD technologies in the early 1980s. At the time of its emergence, the CD was advertised as a noiseless and timeless technology; Sony and Philips notoriously promoted the new medium under the tagline ‘Perfect Sound Forever’. As noted earlier in this section, the CD is designed with the concealment of noise in mind: the effects of noise and error are minimized by an error correction system before they can reach the ears of the listener. It is these hidden, inaudible noises that Tone sought to unlock by overriding the error correction system of the CD player. By modifying the surface of the disc, the CD began to act differently in the playback in ways that had not been intended by its designers:

“A new technology, a new medium appears, and the artist usually enlarges the use of the technology. … Deviates. … The manufacturers always force us to use a product their way. … However people occasionally find a way to deviate from the original purpose of the medium and develop a totally new field.”

In 1984, Tone started using scotch tape with pinholes to affect the playback of compact disc recordings. His first attempt involved a recording of Debussy’s Preludes. The modification of the CD surface affected the pitch, rhythm and speed of the original recording, as well as introducing a stuttering effect that was different with each playback of the CD. Tone recalls: ‘I was pleased with the result because the CD player behaved frantically and out of control. That was a perfect device for performance. (67-8)

And finally, I’ll leave us with excerpts from two texts from Yasunao Tone himself.

Yasunao Tone, “Toward Anti-Music” (1961)

It is surprising that music alone has continued to enjoy a peaceful existence in the secure fortress of forms, when other arts have seen the decline of abstraction and, consequently, the rise of irrationalism. Music has been spared so far because the loss of abstraction would mean the death of Western music as we now know it.. . .

The pure musical tone [gakuon] is not so much sound, but the concept of sound itself. It is like a point in the coordinate system. Compared with the natural sounds around us, the pure musical tone is like a freakish pet produced through crossbreeding over a long period of time.

Musical instruments originated in the tools of everyday life: a hunting bow evolved into string instruments, a grain mortar into percussion instruments. As the development from church music to court music to program music indicates, however, music gradually distanced itself from life and labor.

As a result, in our present environment of earsplitting noise, borne out of human desire and energy—such as the racket at a skyscraper construction site, or the roar of a jet plane or an automobile—there is a group of people whom we call composers, clinging to music sheets, with their ears plugged.

Out of the ashes of tonality [chd-sei], an ardent pursuit of abstract forms in music salvaged a system of serialism. . . .

Abstract music’s anguished decline began to show in Stockhausen’s electronic music: in the progression from the pure abstraction of Etudes I,II to the more musique-concréte-esque sonority [onkyo-sei] of Gesang der Junglinge [Song of Youth]; from serialized compositions to the aleatory and graphic structure of Zyklus. Stockhausen’s problem, however, lies in his basic conception of chance, in his inability to overcome universal rationalism. He had to claim that chance is merely the result of irrational systemic behavior. What he found in such behavior was nothing like Dali’s chaotic nocturnal world exposed to a midday sun.

Now I must turn to “concrete music” which appeared in the wake of the bankruptcy of European abstract music (which ended intellectually with Valéry). What I mean by concrete music is the exploration by European composers of musique concréte and its American counterpart, indeterminate music. They focused on concrete sonority (i.e., actual sound of instruments) in a rejection of the abstract musical tone. Just as electrons and protons oscillate with indeterminate positions and speeds in the microscopic world, so too is the tonal identity “convulsive; other- wise, it would not exist” (to borrow from André Breton). It can be safely said that musique concréte, and the work of John Cage as well, spring from this same source.

A collage of sounds depaysés [taken out of the familiar context ]|—this phrase most fittingly summarizes musique concrete. It may also be called “la musique au défi” [music of defiance] to borrow from Aragon who drew on the concept of collage to characterize Surrealist painting as “la peinture au défi” [painting of defiance ].

Just as Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle negates the existence of electrons and protons as particles within the atom—that is, the concept of matter in classic physics—fixed sound does not exist to Cage’s ear. His school of indeterminate music is named, I believe, after the German physicist’s discovery. Stockhausen’s notion of chance, on the other hand, must have simply been a reaction to electronic music which eliminates the ambiguity of the musician’s interpretation as well as the unknown on the part of the composer. Cage chose chance because it was an essential means to objectify the self.

“La musique au défi” is fertile ground for us.

Nothing will change, however, if musique concrete and the music of chance operation are introduced to Japan as novel techniques. In other words, we are making a fresh start after realizing that Japanese “avant-garde” music always appropriated new Western trends only to imitate their techniques.

[Originally published as “Han-ongaku no ho e” in Guriipu Ongaku 1: Sokkyo ongaku to obuje no konsato (Group Ongaku 1: Improvisation and Sound Objet), concert program (Tokyo: Sdgetsu Kaikan, 1961), pp. 2-3.]

Yasunao Tone, “Parasite/Noise” (2001)

Parasite in French has two meanings which it shares with English. It means an organism living in or on another organism, i.e., the biological parasite, and by extension, the social parasite (sycophant). But the word also means static or noise, as in informational theory. Although the physical existence of my installations in relation to other pieces is taken to have the former meaning, I am more concerned with the latter.

I have previously written of John Cage’s work:

'“Cage’s graphic notations not only disrupt the univocal relation between notes and pitches but are also more open to sound itself, that is, noise. Cage’s suggestion to the students who would like to write an indeterminate score was to observe the imperfection of a sheet of white paper. Not only were the signs he wrote taken into account, but also the stains or smudges on the paper, which are also noise.”

Incidentally, although the contemporary word for noise in French is bruit, Old French used the word noise, the same as in English. In Old French, noise means a noise, outcry, disturbance, a quarrel, derived from the shared etymology of the English and French word, traced back to origins in the noise/noise of sickness and nautical roots. Nausea and nausée are derivatives of the Latin nauseam, and the root is originally derived from the Greek naus. Naus, ship, noise, and the French words noise, nausée, nautique, navire, belong to the same etymon. In short, they are related to the sea, so noise is a sea of sound, pure frequency, uncontaminated by symbolization – or sound waves. Noise is always derivative, as there is no origin in a wave; I am not a source of movement. According to Gilles Deleuze, it is the ‘movement you find in the new sports: surfing, wind surfing, hang gliding [which] takes the form of entering into an existing wave’.

During the recording session for my piece Solo for Wounded CD, my sound engineer Alex Noyse (no pun intended) appropriately observed that ‘it’s like surfing on sound’. So, it is well-founded that Deleuze states as follows: ‘There is no longer an origin as starting point, but a sort of putting-into-orbit. The key thing is how to get taken up in the motion of a big wave, a column of rising air, to get into something instead of in the origin of an effort.’ Therefore, seeking movement is not to rely on some body’s energy, as parasites do, but more importantly to discover the conditions that mediate, in this case, a work of art and the audience.

…

My installation piece uses audio headset guides distributed at the entrance and installed throughout the entire exhibition space. At first sight, they are similar to the audio guides museums distribute for information about the exhibited work. However, my headsets play a text read aloud, which has nothing to do with the exhibited works themselves. Accordingly, the text in Parasite/Noise is not exactly paratext in the terms that Genette implies, because it does not immediately mediate between an audience and the work.

My headsets are, so to speak, pseudo audio guides. Audio guides have a performative function. And just as the perforations dividing a sheet of stamps invite the user to ‘detach stamp here’, my headsets invite the audience to expect a commentary on the works exhibited. From a pragmatic point of view, there is a shared institutional convention between stamps and their users and museum headsets and their users. They share the same functions as paratext. But the text in my headset installation neither informs about nor refers to the works in front of you. The audience will soon realize that the two names, the paratext, of theartist/authors, mean no more than a juxtaposition of two works. Parasite/Noise does nothing more than show the impossibility of the decodification or deciphering of a work. Instead my headset makes the audience interpolate between listening from the headset and seeing the other works. Then the audience is no longer a passive observer and finds the headset to be a tool for use, like Marcel Proust’s suggestion to consider his book as binoculars and Cage’s remark that he is a maker of cameras with which the audience takes photography. This is a case in point for an artistic apparatus I call paramedia. […]

[Yasunao Tone, statement on Parasite/Noise in Yokohama International Triennial, exh. cat., ed. Nobuko Shimuta, et al. (Yokohama: Yokohama International Triennial, 2001) 337 [footnotes not included].]

Thanks for the great report on Yasunao Tone's life & work - he will be greatly missed.

Achim Wollscheid might occasionally be tardy but he's still very much with us. I just received an email from him on May 9 regarding tech for an upcoming event in Frankfurt.