Our second guest post from Gianmarco Del Re. We first heard from artists in Ukraine, while this time we hear from Russian artists: GOST ZVUK, RIA DAR, EVA REICHER, RICAAI, FORESTEPPE, and ELINA BOLSHENKOVA. (JS)

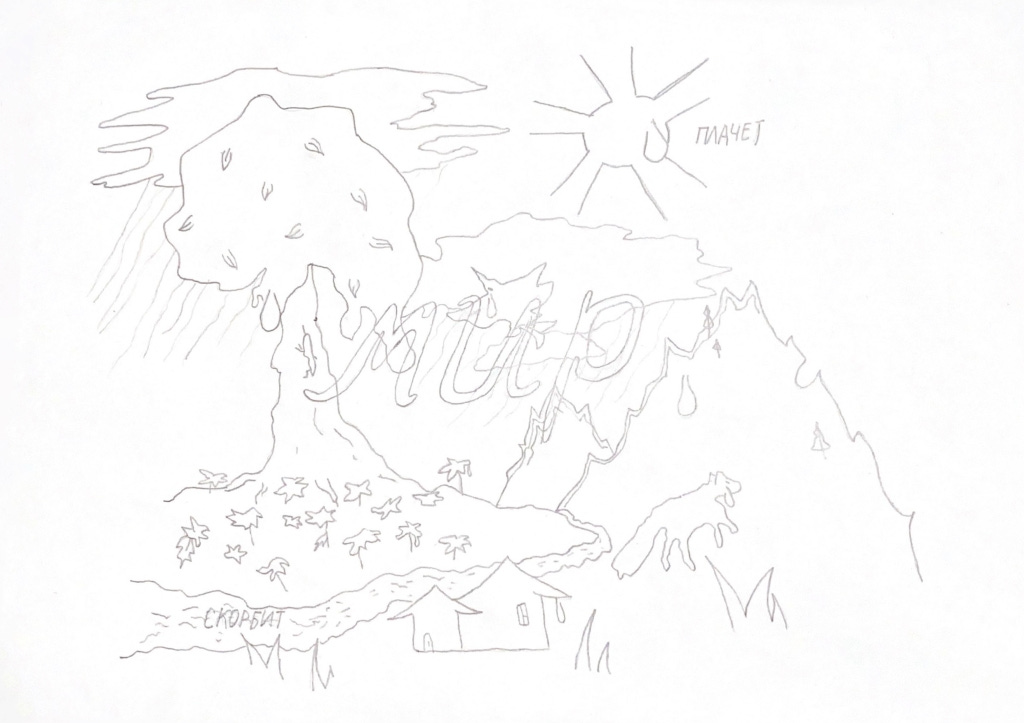

Mир / Mir

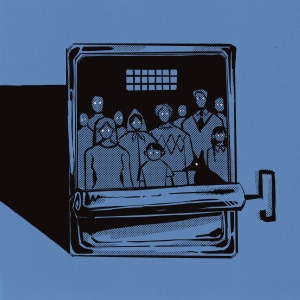

In Russia, more than 15,000 Russian citizens have been detained between February 24 and March 20 for protesting against the invasion of Ukraine, according to data from monitoring group OVD-Info.

Russia’s parliament passed a law criminalizing the distribution of “fake news” about the Russian army with up to 15 years in prison.

Сalling for people to attend anti-war protests in Russia now carries a penalty of up to 5 years in prison.

Freedom of movement has been curtailed, primarly due to Western countries closing their skies to Russian planes and viceversa. The closure of 11 airports central and southern parts of the country has further complicated movement within Russia.

Many Russian artists have taken to the streets and contributed to a number of fundraising compilations against the war. Some have now fled the country.

A number of them have families and relatives in Ukraine.

My name is Ildar and I founded Gost Zvuk in 2013. I was born in 1985, so basically I’m a kid of the MTV era. Of course, it influenced me a lot – I was into rock music, later got into hip-hop, jazz, funk, soul, and then into the electronic music scene. I was investigating the IDM genre – Warp, Ninja Tune, and everything Autechre. Later on, I fell in love with our own cultural heritage – the vast palette of Soviet and post-soviet musicians. Artists around me are still my key source of inspiration.

How would you define the music scene in Moscow specifically and on a more general note in Russia?

The local music scene as an institution was almost non-existent a decade ago, even though we had certain musicians and cultural activists. We were excluded from the global and especially Western agenda, our artists were not traveling around the world and few were releasing their music on foreign platforms. But after a decade of hard work we gained a lot of attention, we had amazing connections with the established music scene. We became a respected part of the global music movement. We have initiated a lot of educational processes. We changed the perception of modern music culture in Russia. Our collective input was never respected by our government and, finally, it was destroyed. But I must say I feel much more sadness for the destroyed cities, killed people, and broken destinies.

How has Gost Zvuk evolved over the years and what would you consider your greatest achievements?

I think that the most important thing that we were able to do was to help many local musicians believe in themselves. I also hope that my greatest achievements are still ahead.

Considering your label is dedicated exclusively to the Russian and ex-USSR scene, how would you describe the experimental scene in Ukraine?

I respect and love the Ukrainian scene. It has its own spirit, it’s different even though we have certain cultural roots. Still, I believe our scenes were extremely connected. We were always trying to support and complement our musical movements. We were inviting, releasing, spreading the knowledge about Ukrainian musicians throughout this decade and it was a mutual thing.

You started releasing albums in 2016, which coincidentally is the same year the Ukrainian labels система | system and Corridor Audio, for instance, have also started operating. Coincidence, synchronicity or were conditions especially favourable and fertile at the time for your countries?

Our first release came out in 2014, but overall it was a period of great hopes for both countries.

How has the live scene been impacted by the pandemic in the past couple of years and has lockdown affected your creative output?

Well, I think it’s just like everywhere in the world. It almost destroyed club/event culture, we were not doing live gigs and almost entirely focused on music production, releasing new music, and trying to survive.

You released the fundraising compilation Stop The War! in solidarity with Ukraine. What has the immediate feedback been on both sides of the divide?

Well, our reaction was instant, every musician I wrote to sent their music rapidly, without any thought, and expressed their solidarity and deep sadness. A lot of them went to the streets, several were arrested. We expressed our stance from day one – we stated that it’s a crime against humanity and we are against it. We have raised funds for humanitarian needs, we have supported friends with direct money transfers. I left the country to secure money transfers and overall operations. Our Ukrainian friends believe that’s it’s not enough and I do understand their feelings.

Has the war already changed, the way you operate Gost Zvuk and what impact do you expect it to have in terms of operational costs and output? In other words, will, for instance, selling and shipping merch to Europe become no longer possible or viable?

Of course, it’s affecting directly the way we are operating. We don’t know yet about shipping, money transfers, further Paypal operations. We can forget about foreign acts and international collaboration. We are entering the phase of canceling everything Russian – even for those openly against the regime.

Considering we are already seeing Russian artists and culture being cancelled, are you worried that the Russian music scene will become increasingly isolated and insular?

Sure thing. I already accepted this fact. For the time being, I was thinking about ceasing all operations. But the mission of the label was always about supporting local voices and changing the way Russian culture is perceived worldwide. I realised that our mission is now more important than ever.

Can music provide refuge in these dark times?

History shows that music was always providing refuge in the dark times.

Finally could you recommend a book / film / artwork about Moscow / and or Russia?

Book – Day of the Oprichnik by Vladimir Sorokin. Quite a visionary novel about the modern Russia, written in 2006.

DARIIA RIA DAR

I am a researcher born in St Petersburg. For the past two years I’ve been working with sound as my main medium, however I have been practicing music throughout my whole life.

What is your studio set up and what is your favourite piece of hard/software?

My portable studio consists of my voice, laptop (optional) and headphones. Recently I had the privilege of working with bass guitar thanks to a dear friend.

How would you describe the experimental music scene in St Petersburg? And what would you locate it in relation to Moscow and other parts of the country?

It all started for me at the “Pushkinskaya 10” Art Centre, home to the Experimental Sound Gallery (ESG-21). The balcony from my room was across the road from their balcony, so that was the first place where I heard sound art. I only went to a concert there once, since I was a shy teenager. But every night, when I knew there would be an event, I would just bring a chair to my balcony and listen from there. So, for me, the St Petersburg scene is something secretive, personal, but also punk and nonconformist.

In Moscow it is hard to describe the music scene, as it comprises people from many parts of the country. So the scene in general is more diverse, and more open. Unfortunately, I don’t know about the rest of the country. But I went to the Bryansk festival “Iskorka” once, and there I’ve felt that punk vibe that I’ve missed since moving to Moscow.

Could you give us a sense of the mood on the ground in the past few weeks and how would you characterise the response of the artistic community?

Since February 24, Russia has been at war with Ukraine. I’m in a safe place now, so I can call a war “war”, but up until yesterday it was illegal for me to do so. Since the beginning of this unspeakable tragedy, we have tried to protest, but it wasn’t enough. We began to leave visual signs so that people could see there was a community protesting, and could unite, speak out, fight, and think. This was enough to make a friend wanted for extremism.

The safe zone of the artistic response is now uncertain. We are trying to support each other within our community and to support humanitarian organisations, who help those who still try to fight, even at risk of long imprisonment.

Considering current laws, how can one support Russian artists who speak out?

If you want to support, you can speak publicly about cases of state injustice, and police violence toward artists. You can donate to some of the humanitarian organisations (because most of the creatives in danger get help from these organisations, but you must check beforehand, if these organisations are marked “foreign agent”, those are the only organisations you can donate to as a foreigner.) You can support releases such as this one The wind blows wherever it pleases. You hear its sound…, because it makes you hear the voices of those who have the strength and courage to speak out now. Also there are Russian labels who donate their income to Ukrainian organisations, for example the Neoplasm label. In general, you can keep up with the news of any Russian label you know of, because most of them post actual information on how you can help their initiative.

How has life changed for you on a practical level?

Oh… well it’s hard to remember what life was like before February 24. The country I’ve considered my homeland became foreign to me. In just a month, everything changed: current laws make me a criminal, there is no freedom anymore. People have become poorer, more distrustful, unemployment has become very high, as many companies have left Russia. The cops have become more aggressive, and now they have more rights than citizens. My day consisted of waking up, reading the news, plastering protest stickers around town (at night, because it’s illegal) and that’s it.

The only thing I could hold on to, with the world falling apart, was my family and friends. Now I’m scared for their safety, because we became traitors to the motherland, for believing that depriving people of their lives and homes is inhumane. I grew up in a city, where everyone remembered the siege during WWII, it was unthinkable and the worst I could imagine. And now there is an ongoing siege of Mariupol.

I’m still a bit delusional, because it all seems like a nightmare I can’t wake up from. When yesterday I fled the country, the plane had to make a long detour to avoid Ukraine. So we flew for a very long time and the only thing I could think of was that somewhere near, from that exact angle Russian Iskanders destroy cities and people’s lives.

Are you still able to be creative, or is this not something you can currently think about?

Right now I try to collect and document anything I can find, and for me working with words and visuals seems more appropriate. Also, my friend yxlite and I have a musical project that reflects the uncertainty, the inappropriateness of the musical language now, a kind of numbness and anticipation for what keeps happening. But my main focus at present is to do anything I can to support those who can’t leave Russia, and for those in Ukraine.

EVA REICHER

I am a sound artist from Samara, Russia, currently based in Moscow. I always wanted to be some kind of pop singer, but I abandoned that idea after immersing myself into contemporary art in my very first semester at university. So I’ve been making my silly little music since childhood, but my art career started about 3 years ago. I’ve always wanted to make social and political art because I thought that’s the main purpose of it. Basically, all my projects can somehow be connected to it — for example, sound installations about my sister’s experience in the temporary Detention Center in the village of Sakharovo, a music piece about the government causing the apocalypse, a live set containing speech from the arrested DOXA journalists and so on.

How would you describe the experimental music scene in Moscow and in Russia?

I think it was doing well before the 24th of February. There were some ethical issues with the fees we were paid for our work, and the scene centralising in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, but I thought my colleagues and I were doing our best to make it better.

Could you give us a sense of what the general response has been in Moscow to the events of February 24?

I was protesting almost every day since the beginning of the «operation» until I got arrested on the 6th of March. I didn’t feel like the response in Moscow was that massive and I think that’s because the news was too shocking for us at the time. Today, a month later, I can feel the ice cracking but I’m embarrassed that it’s taking this long for Russians to finally awake.

You released the fundraising compilation мир (peace) together with RICAII. What was the repose from the artists you asked to join the project and how did you go about compiling it?

We didn’t actually even ask anyone to join personally — we just asked some of our colleagues to share the post about the project and maybe, if they were interested, take part. The response was huge, especially from visual artists, performers, writers, art critics etc who were all willing to contribute. Even though our work is currently on pause because of censorship, no one is quitting. Now we’re all patiently waiting for the release of vol. 2 and 3.

Could you explain what happened with the distributor?

They got scared because of the new laws and deleted our compilation without any explanation. They also refused to release our next ones.

How can one support Russian artists who speak out?

The best support is in sharing and letting the world know that Russian artists are against what is happening right now. All of my friends and relatives are experiencing an enormous sense of guilt because of our government and our nation. Everything they let us see is covered in Zs and propaganda. We don’t know how many of us are fighting so it is important to show that we are not alone in this. And for the artists in danger, any help with relocating can save lives.

Have things changed for you on a personal level?

Of course. I’m forced to leave my country, my university, my family and my job here and I don’t know how to start rebuilding my life elsewhere. But this is still nothing compared to what my Ukrainian friends and relatives are experiencing right now.

Are you still able to be creative or is this not something you can currently think about?

Before February 24th, I’ve been suffering from some kind of a writer’s block, but nowadays I feel a lot of strength to make art and speak about it. Now, I think my art finally makes sense.

Are you afraid that even dissenting Russian artists will be ostracised and what can be done to prevent this?

Yes, I am already scared of it, but sadly only the change of the regime can prevent it, nothing else.

Could you recommend a book / film / artwork that for you encapsulates present day Russia?

Sorokin’s novels are all prophetic. Also (obviously) George Orwell’s 1984, Масяня (Masyana) and the new season of Attack on Titan.

[At present the artists are unable to access any donations from Bandcamp for this particular release due to paypal pulling out of Russia. They recommend sending money to Ukrainian foundations or, if Russian or Belorussian, to donate to Russian foundations such as Ovd Info]

RICAAI

I am a sound artist, musician and curator from Moscow. In my work, I experiment with various technologies and sound practices, working with concepts of alternative knowledge: occultism, spirituality, sacred texts and any other non-traditional views of the world that can give us a special subtle sense of the world. I share knowledge and experience that have made me closer to naturalness, that have helped me to become freer, more conscious and healthier in the most global sense of the word. And today, it seems to me, sharing this knowledge is more important than ever. Because cruelty, injustice and horror have always existed around us. And the best way to resist this negativity is to share knowledge that brings one closer to nature, gives one health and conveys this subtle sense of the world. Because, after all, healthy and conscious people create peace.

It is difficult to understand this subtle feeling through the emotions that we are experiencing today, difficult to see it with a lucid mind. This feeling is uncovered through philosophy, soul, intuition, time, experience, and, I hope, art and music. Therefore, today, it is still as important as ever for me to explore my creativity.

In recent years, I have experienced in Russia a unique experimental scene that has been growing rapidly, taking example from the West, and in some way, from more developed and organised markets, projects and cultures. But at the same time our scene did not lose its local authenticity, which is what made it so interesting and strong. However, today, perhaps, we are losing a key element of the authenticity of all our art – an honest and harsh reflection on the difficult and original fate of the Russian people, because right now it simply would not pass the censorship.

However, our artists have always found a way to express themselves. Even at the time of the strictest censorship in the USSR, when even instrumental music was censored, artists skillfully hid their true message deep in the notes. Over time, the situation changed and, at some point, it even began to seem that Russia was confidently moving towards Western freedom of expression. This was especially noticeable in the 2010s, or so it seems to me. And until recently, it seemed that most artists could freely and even boldly criticise the regime. Some did it subtly and beautifully, and others did it stupidly and directly, but almost everyone was allowed to do it. Only a few were unlucky enough to attract unwanted attention.

The punishment in such cases were completely different: from simple censorship to long term prison senteces. I have a feeling that all this was done in order to consistently remind people of what might happen for being too bold and and to remind them that they still live outside of Europe. Or maybe the law enforcement system was working so badly that it simply could not control the huge flow of art and music that spread through the information channels and technologies that came from the West, and only paid attention to those cases that caught their eyes. But now, finally, everyone has apparently begun to realise the incredible influence of the Internet, of music and art and is very quickly looking for a way to strictly control all this. Which is exactly why art and music in Russia, as we have known it in recent years, is rapidly degrading to the state in which it was during the Soviet era.

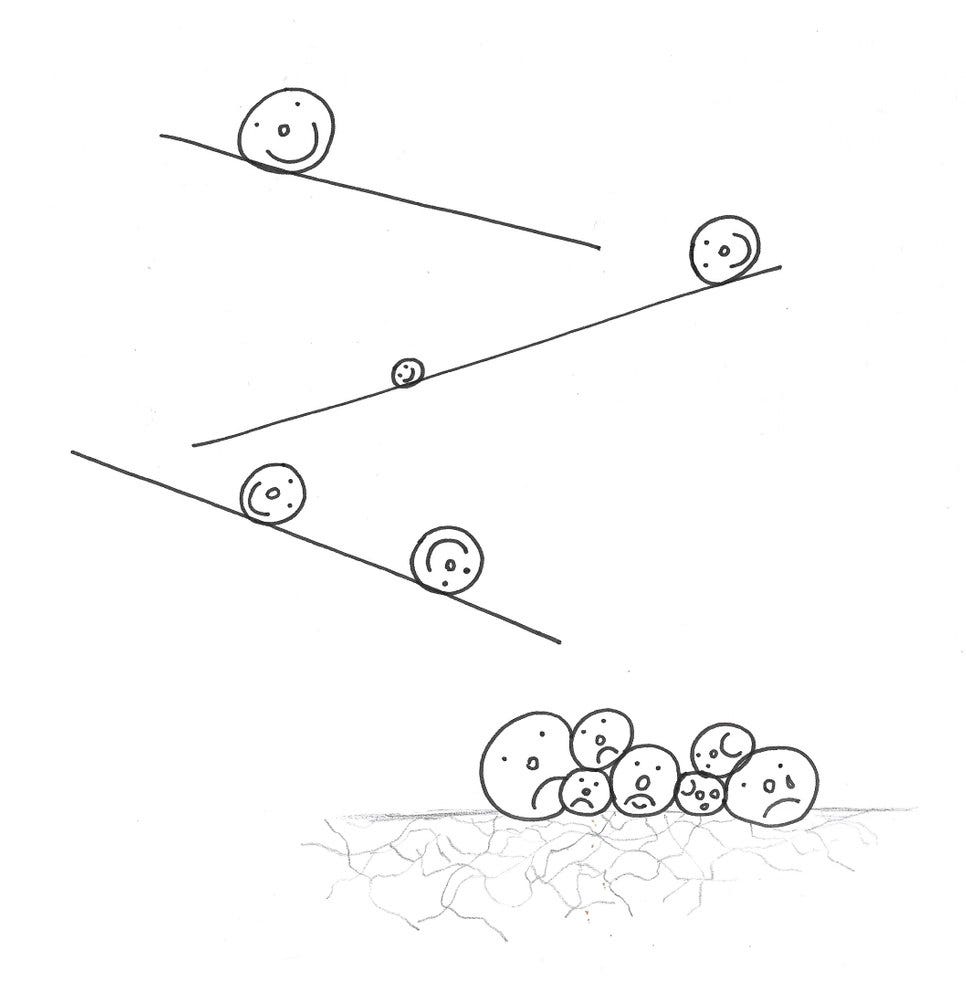

Our artists reacted to the events of February 24 in very different ways. Of course, like all people, most were simply shocked and experienced a sense of loss. I noticed that many artists lost faith in their music.

Against the background of such events, art and music feels meaningless to many: “How can one write music when all this is happening?” This hit particularly hard those who in peacetime were apolitical and created entertainment, which today may feel inappropriate. For example, a friend of mine who used to make a huge amount of music every day, just stopped and said that he just didn’t know how to continue after all this.

On the other hand, I noticed that for many people music has become a kind of therapy, with two opposite approaches – escapism and activism. Escapists seek salvation in music from the noise of the outside world, news, cruelty and public pressure. For them, music is a separate world where one can hide from anxiety. For example, this is how I shared the song “Утекай Тревога” (“Flow away, an Alarm / Anxiety — wordplay from Russian) on the first Mir compilation, which I actually wrote initially just for myself, in an attempt to calm myself. I just sat in the studio and sang these words for several hours like a mantra until they spontaneously turned into a lullaby, which actually relaxed me and, I hope, will also calm others.

As for “activists”: of course, many people today find the desire and courage to speak out in their music. For them it becomes the only way to somehow alleviate their suffering. Therefore, the productivity of such people increases, because there is a feeling that their skills, whatever they may be, are still needed – to spread the truth, to support those who are having a harder time than they are, to continue to inspire, to help people relax and reboot, to help them laugh even in such difficult times and hope for a peaceful life.

However, today, we found ourselves in a situation where one can’t please everyone. Someone may be annoyed by the fact that you continue to make music at such a time, someone – that you have stopped making it or are not doing enough. Someone will be unhappy that your music is not political enough, or have the wrong kind of politics. I believe that the main thing now is to preserve inner peace. Peace begins with each of us. And when we create music, peace continues in it. And one should never be ashamed of such sincere art, because there will always be someone who really needs it.

These are the reasons why we decided to create the Mir project — a series of music collections by completely different artists united by a common desire for peace and support for all those who are having a hard time today. We wanted to remind people and the artists themselves that now is not the time to give up. On the contrary, today it is more important than ever not to be silent, even if we are silenced. Let our voices be instruments and our speech be music. When we make art with them, we make Mir. (“Mir” means both “peace” and “world” in Russian. Perhaps, because we can lose the world if we lose peace.) It is even difficult to call this project curatorial because we did not conduct practically any selection of compositions. Our idea was just to abandon the selection and create a single platform for anyone who sincerely shares our concerns. We just wrote to all our friends and colleagues hoping to collect at least 4-5 tracks, and after a couple of days we have already collected 14 tracks. And a week after that – another 18 for the next collection. We have received incredible support for this initiative. This is when one realises that strength really is in unity.

I was born in Chernihiv in Ukraine and grew up in Novosibirsk in Western Siberia. When I was 10 years old, my uncle taught me how to re-record music from records and CDs to cassettes. Then I was taught to play the guitar, I played pop rock and shoegaze in bands, and formed a post-rock one man band, Последние Каникулы. In the end, in 2012, under the Foresteppe alias, I returned to the practice of working with magnetic tapes, and began to explore the interaction of this medium with field recordings, sounds of acoustic instruments, and samples from Soviet cartoons. Since then, I have developed my music creativity mainly in connection with this project. In 2020 I moved to Moscow.

What is your studio set up?

After moving to Moscow, I have been living in a rented apartment, where there is not as much space as I had in Siberia. Therefore, the studio set up is always in a disassembled state. There is a small table on which I place cassette or reel-to-reel players, or casiotone with a mixer and pedals, or toy acoustic instruments. It all depends on what I’ll be working with.

The label Klammklang has showcased a number of musicians from Siberia like yourself. How would you describe the experimental music scene in Russia away from the main cities like Moscow and St Petersburg?

It seems to me that it is difficult to talk about a single regional Russian experimental music scene. There are separate communities of different sizes, as well as musicians who stand apart. Probably, in this sense, the community of Russian experimental musicians is a bit like Russian society – it is very atomized.

You have contributed to a number of fundraising compilations following the events of February 24. Could you give us a sense of the mood on the ground in the past few weeks and how would you characterise the response of the artistic community?

I’m not sure that I have the right to speak for the entire artistic community, but personally I had a state of numbness in the first few days. I am a historian, and the outbreak of current events stunned me not only by their scale, but also by their monstrous justification.

I understand you are part Ukrainian and have family in Ukraine. Have you been able to have regular contact with them and how are they?

Yes, my mother is Ukrainian, her relatives live in Chernihiv. Plus, my own sister went to visit them in February and crossed the border just a few hours before the invasion. A month has already passed, they do not leave the house, and during the shelling they hide in the basement. For the past two weeks there have been considerable problems with electricity, gas and water. My sister was going to flee to Europe, but this week a bridge in Chernihiv, that led to the road to Kyiv, was blown up. Now, she doesn’t know what to do. But we have the opportunity to chat via messenger almost every day, thank God.

Considering current laws, how can one support dissenting Russian artists?

If we are talking about financial support, then there are practically no channels left for this (at least, Paypal stopped working in Russia). But I never made my music my livelihood. My day job is as a teacher at a private school, so the new situation has not hit me financially yet. On the other hand, if we are talking about moral support, then it is very simple: listen to music and share it with your friends 🙂

How has life changed for you on a practical level?

So far, life hasn’t really changed. Yes, store prices are going up a lot, but there is no economic default or hyperinflation yet. I also installed an app on my smartphone that blocks access to instant messengers, so should the police carry out a sudden search, they will not be able to find any statements that could bring me to justice under the new censorship laws.

Are you able to still be creative or is this not something you can currently think about?

To begin with, I couldn’t think about it, but now I’m actively working on several projects. It became clear that the plans that I had been hatching for a long time must be implemented without waiting for a more comfortable time. Who knows, maybe soon I won’t have the opportunity to be creative at all. As long as it’s there, there’s no time to waste.

Has your experience in the military shaped your response to current events?

Yes, absolutely. After returning from the Russian army (I was unable to avoid the mandatory military service in 2017-2018), I hoped that this experience was a thing of the past for me. Army life is a real parallel universe, with inverted values. Kindness in the Russian army is weakness. Also, if you have any skill, it is best to hide it or they will take advantage of you. So, for instance, if it suddenly turns out that you know how to work with documents, officers can throw a huge number of bureaucratic tasks on you (this was the case with me).

I thought that this universe would not go beyond the military. I have done several works related to understanding this experience, and I was going to finally do away with this topic this year. Unfortunately, this militaristic abscess burst. The idea that two universes could exist in parallel now seems naive and even careless.

The bitterest thing is to realise that most of those who now support the state, or are neutral, are unlikely to ever admit they were wrong. Because it will mean that their whole life will lose meaning. Throughout the 20th century, people were taught to love the state first of all, and now it is impossible to sharply reverse these beliefs.

But the state, speaking of love for the Motherland, in fact uses people as fuel. Now we are at the next round of negative selection of the creative population in Russia – reflective people leave the country or are persecuted by the state. Nothing good will come of it for Russian society.

I am a musician and artist. My field of interest is electro-acoustic music with the use of accordion and voice. I am also involved in various art projects – working with sounds for a performative installation for example, or co-curating the community radio, Radio Fantasia. I’ve worked with sounds for almost 3 years.

You also work with moving image. How do you combine the different practices?

It started as a feature of my university education – I studied animation there, taking extra courses related to sound. I consider my practice as a whole. The images and videos I make exist in the sound continuum, as I make music videos and videoart for musicians, album covers and more. I strongly believe this helps to remain insightful and gives the opportunities to refocus when one truly needs it, and one practice always nourishes the other.

How would you describe the experimental music and art scene in Moscow?

If I were asked about experimental music before February 24, I would say it was flourishing – I don’t know how to describe it in the new circumstances, because everything kind of stopped for obvious reasons. We had a lot of stuff going on, very diverse artists. This is also as a result of the educational opportunities in sound art which started to appear in Russia. I hope the whole scene will be able to develop further, but it seems unlikely.

As for the contemporary art world – despite my small involvement, I can’t say much about it. I’ve always been pretty distant, in my worlds of music and cinema.

Could you give us a sense of the mood on the ground in the past few weeks and how would you characterise the response of the artistic community?

I can only speak for myself and my inner circle – we all felt that our lives were over in one day. This is a feeling we probably won’t get rid of. Personally, I have gone through the worst mental breakdown with suicidal thoughts. The future was stolen from us following the theft of people’s lives, which incomparably worse, I realise that. I’ve never felt so unwanted. At first I thought we could invent some powerful ways of resistance, now it is more of a helpless feeling.

A lot of people attended the protests, many of my friends were detained and fined. Now the protests lack leadership because almost everyone who could coordinate them is in prison or has left the country under threat of persecution. The police have more power than ever. There have been reports of torture of detained protesters at the police stations, and explicit nazi symbols are being spread.

The television images are very different from the ones on independent media, so in fact there are many people who do not know the truth or support the “special operation”, like my older relatives, for example, with whom I can no longer communicate in a normal manner. Ignorance is still bliss for lots of people. This is what scares me the most.

The atmosphere in Moscow right now is reminiscent of George Orwell’s 1984. It’s now a criminal offence to “discredit the Russian forces”.

From my experience, people who understand the scale of tragedy are those who work in the culture sector, the artistic community, and the so called middle class we had in Russia. Generally, these are the young people under 40. Dissent began to pass through art – open letters, actions, leaving government funded projects, but activists end up in danger, and many have already fled. I think that politically aware culture has never been welcome here. Now, in a situation of isolation, the authorities have a chance to get rid of anyone who produces dissenting ideas.

Also, I have to say, the amount of support received from my foreign friends, musicians, artists, is truly impressive. All I get are kind words, and I feel that the music community is a great safe space for me now. I am grateful to all my friends who have been present in the moments of crisis, to those who are far away and those who are by my side at the moment.

Considering current laws, how can one support Russian artists who speak out?

There are not many options for direct support because of the sanctions, and it is better to send money to Ukraine and refugees now.

Also, not making people who speak out feel isolated is crucial. If you are an institution, make sure you don’t cancel opportunities for people at risk in Russia.

How has life changed for you on a practical level? I understand for instance that it is difficult to travel.

I didn’t have much opportunities to travel earlier, I’m not really privileged and had started earning some money shortly before February 24. Money is being devalued, so my small savings have melted away and I’m once again poor. Yes, traveling is definitely cancelled for me, selling music on Bandcamp too and that’s the only place where I could make money from my music. I think the independent artists and labels who actively used Bandcamp are in a really bad position.

I am also in a precarious position workwise, but hopefully I won’t lose my job. Again, these are not big problems compared to what’s going on in Ukraine. In addition, it seems that I will not be able to get medicine in case something happens to my health condition, many of my friends or their relatives are facing this problem right now.

Could you clarify the situation about Bandcamp?

Right after the sanctions came into place it was still possible to transfer money from paypal to a credit card but getting anything via paypal is now impossible. A friend bought my release on the night paypal pulled out of Russia and I never got her 15 dollars. Also, any money transfer via Swift is now impossible.

Are you able to still be creative or is this not something you currently think about?

I haven’t held my accordion for a month. Now I’m returning to practicing because it helps to keep the mind clearer. Basically, art practice feels unnecessary and meaningless if not for therapy purposes. A friend said that from her perspective most of the dissenting voices are those of artists, and that we should continue our work spreading art. Maybe she’s right. However, I feel all these discussions are inappropriate in the light of current events. May there be peace.