To quote Carl Stone, “Phill Niblock has changed the frequency.”

Over at the Quietus, our friend Lawrence English eulogizes the great artist in “The Ever Present : Remembering Phill Niblock.”

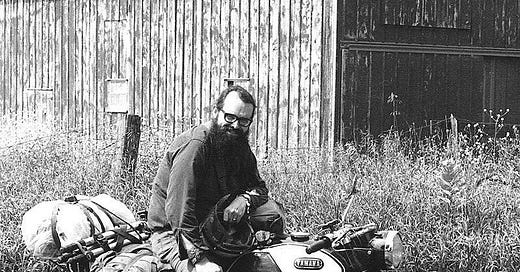

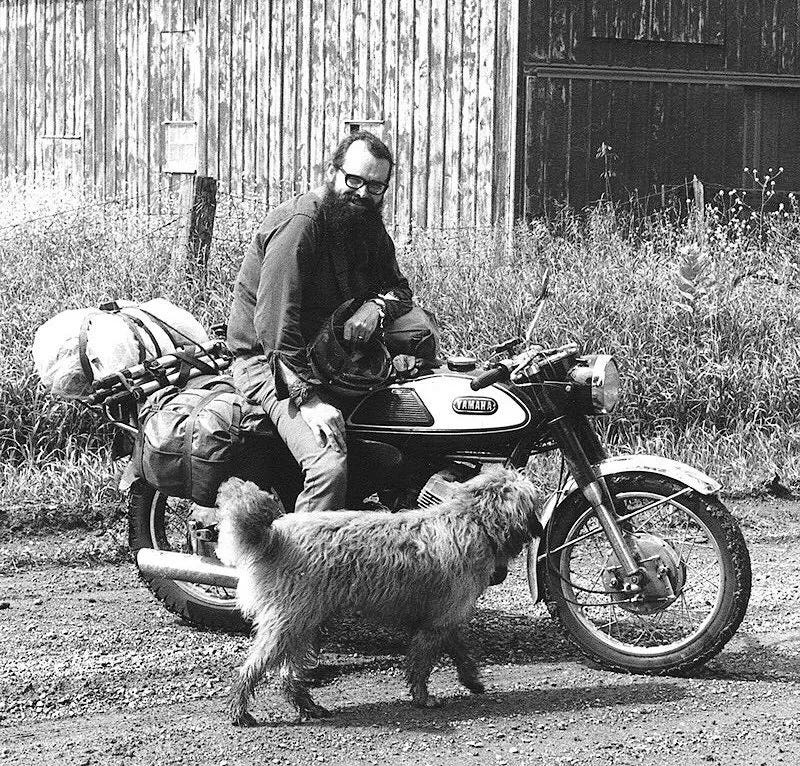

Phill Niblock once wrote of his recordings, "You should play the music very loud. If the neighbours don't complain, it's probably not loud enough." It’s this statement of intent that has come to capture a great part of his way in sound, and music. It is offered, I am sure, with that gentle wry smile that would often occupy Phill’s face and is testament to the glorious possibility of his music. A music forged by his maverick desire to consume the body and the mind through sound, and celebrate the body as an ear.

That penchant for high volume certainly influenced many artists, including Tim Hecker and English himself, who cite Niblock as an influence.

In a 2007 interview with Paris Transatlantic, interviewer Bob Gilmore asked Niblock “Have you always been into loud sounds?”

Two answers to that. One is that the overtone stuff really works better at loud volume. Two is: I started to listen to music and began collecting records around 1948. And it was fairly soon after that that hi-fi came about, so that it was possible to have really good sound – LPs and tapes and speaker systems. The whole thing came more or less at once. The famous demos were Acoustic Research – they'd do demos with a string quartet playing with the speakers on the floor and the quartet would stop playing and the speakers would continue. And those speakers didn't even sound very good! So I made my first really big speaker system in 53. That's when I had my first tape recorder. I had a cabinet maker make the system from designs. It was a Klipsch design. I met Paul Klipsch in 52. I was a Klipsch dealer for a short time, in 73. In fact I was on the way to Mexico to shoot a film and I stopped on the way in Arkansas and saw Klipsch and sort of talked him into letting me be a dealer. I'm really very interested in sound. And so that made it possible suddenly to have sound from speakers that you could have around in the home.

But beyond his work as a composer and filmmaker, Niblock was a cultural connector and mentor, and his Experimental Intermedia loft in New York City, with a satellite in Gent, Belgium, hosted many thousands of artists for over five decades. So many of the tributes we’ve witnessed since news of his passing broke have focused on Phill as a person, a mentor, a friendly face, an encouraging voice. Back to English’s memorial:

This morning, it felt as though my entire social media feed was photos of Phill Niblock, and often photos of other dear friends with him. The thing about Phill was that he was a connector. He loved the idea of community, he loved people, and he loved conversation. The examples of this passion for connectivity are scattered across his lengthy time amongst us. The most prominent example is perhaps the NPO artist support group Experimental Intermedia which he directed from 1985. XI, his loft performance space and later label, has been an ongoing node on the network of experimental art and performances spaces for decades. Occasionally, historic posters and line ups of some of the events he produced will surface. These gatherings, the artists whose work has carried forward so many ideas and inspired so much, are all there. They were sharing that space and that time, in that place. It’s a marvellous thing to see and even more so to imagine.

When I started my PhD in 2014, I gained access to the DRAM online archive of American music. I was quickly overwhelmed by the scope of the archive, so I decided to search for recordings made at Experimental Intermedia as a means of limiting the results to a manageable level, finding recordings of David Behrman, Arnold Dreyblatt, Arthur Russell, and Ulrich Krieger, later adding Yasunao Tone and many others. Many artists well-known and otherwise found EI as a welcoming space upon moving to NYC, or just passing through. Some of my Neapolitan friends Aspec(t) [SEC_ and Mario Gabola] played there in December 2014, though I wasn’t in town at that time. But I’ve heard from so many people over the years how affirming playing at EI was for them, including Lea Bertucci, who I interviewed at UNSOUND 2018 for what became the first episode of the Sound Propositions podcast.

I didn’t know Phill Niblock personally; I only met him once, when he and Katherine Liberovskaya were in Napoli to show some films in late July of 2018. I had just arrived in the city which was became my homebase in Europe during the 2018-19 academic year, conducting research for my dissertation, and my friend Renato Grieco invited me to the event, the first of many great concerts and exhibitions we went to that year. The program included films (and music) of Phill Niblock and Katherine Liberovskaya, and while I’d seen the DVD of Niblock’s The movement of people working (2003) [Vimeo], I was hypnotized by the effect of their work in this context. Each produce work that, in different ways, might be described as visual drone. One understands immediately how the duration of the film will play out, but this isn’t a detriment. For instance, in Liberovskaya’s work, with a score by Niblock, we see grains of rice removed off-screen one by one, or ice cubes in a sink slowly melting, or a rake being dragged across a sandy beach. This is not filmmaking driven by plot, but an exploration of time and gesture. This phenomenological aspect of drone is explored visually and sonically, compounding the effect.

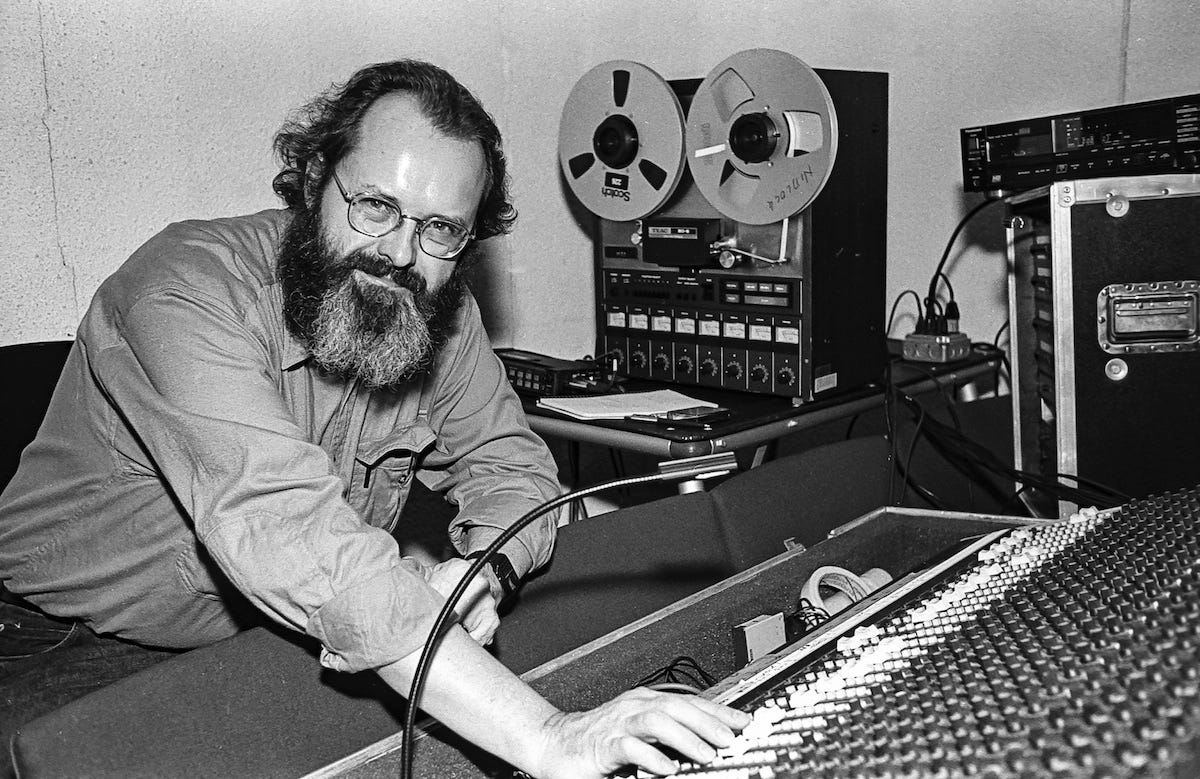

Niblock pursued singular approaches to music, developing an idea he had in 1968 to work with attackless endless drones of close pitch intervals, creating complex harmonic interplay. For more on his background and practice, I recommended Geeta Dayal’s 2016 interview “A Sense of Time,” published by Frieze. His production process changed over the years, from working with live musicians and tape to editing in ProTools, but that singular vision persisted until the end. As the title of a 2006 interview for the Wire put it, “No Melody. No Rhythm. No Bullshit.”

In preparing for an interview with Christina Vantzou (published in early 2016) I had I thought of Phill Niblock as a point of comparison for a variety of reasons: as an “intermedia artist,” his approach is that of a non-traditional musician; he also works with film, and with 16mm, as does Vantzou; he’s based in Belgium; his work tends to utilize classical instruments; it is a kind of drone (though quite different from Vantzou’s work); and most relevantly, he faces perhaps similar challenged in scoring compositions for orchestration. In an interview with Paris Transatlantic, he notes that “pretty much the ProTools file is the score of the piece.” I found this formulation to be incredibly generative, changing how I think about composition as a practice.

For an artist with such a long career, there was no pretension to the man. One of the most common quotes I’ve seen circulating is the following:

I just did this 3 hour concert in Luxembourg and it was all on one file. I play the file and then play solitaire on my phone, out of sight. I practice a lot.

I’ve seen Phill fall asleep during performances before, and I know I’m not the only one. Who can blame an old man for taking a nap, let alone when his set is going after midnight. But the thing is, whether he’s just pushing play, playing solitaire, or snoozing, it didn’t matter. It was about the sound.

I saw him perform at Unsound Krakow later that fall, after the encounter in Napoli. He was scheduled to begin playing at 10:30pm, the first act in the not-so-chill-out room in the basement of a late-Soviet era hotel. If the dance-floor is too much to bear, the drone room was meant to be a place of respite, but in fact Niblock’s music was often way more intense than anything going on upstairs. What a way to celebrate his 85th birthday. A true inspiration. Here’s what I wrote in my review of that year’s festival:

Niblock performed on Saturday night at the “Secret Lodge,” a circular bar area in the basement of the Forum hotel, adjacent to the bathroom. The Forum hosted UNSOUND’s club nights, with three different halls on the main floor dedicated to different strands of dance music. The Secret Lodge, by contrast, was billed as something of a chill-out room, a place to take a breather from the intense spectacle and kinetic crowds above. Performers ranged from more downtempo DJs to jazz ensembles. Covered in carpet from floor to ceiling (including the floor and ceiling!), the entire room smelled like the bathrooms had overflowed more than once over the years. The prominent Bulleit bourbon whisky sponsored bar could do little to salvage the vibe, but somehow it all worked. While many patrons were certainly chilled out and dozing off (as was Phill himself on occasion), the music was anything but relaxing. Since trading tape editing of acoustic instruments for composing in Pro Tools two decade ago, the intensity of Niblock’s music has increased along with its density. While Huerco S.’s Pendant project floundered up above, a muddy mess going nowhere slowly, Niblock showed how crushing and powerful electronic music can be without adhering to the clichés of club music. The tremendous volume has the effect of amplifying minor shifts in timbre or tone, the constant momentum crushing the listener into an odd stasis, like standing in a rushing river. His late-night performance was accompanied by a screening of work from his film series The Movement of People Working, depictions of the dignity of slow human labor, in stunning Kodachrome. Sometimes the Old Guard does it better.

Niblock is probably best known to our readers for his pioneering drone music. His downtown NYC loft, Experimental Intermedia, has hosted countless performances over the last five (!) decades, and mentored artists from around the world. 2018 marked 50 years since Niblock’s first musical composition, and also his 85th birthday, so it was a pleasure to see him receive pride of place in UNSOUND’s programme. His output didn’t seem to be slowing, either, with a record topping our best of lists in 2020, and reviewed as recently as 2023.

Even though I grew up in NY, I moved to Montreal in 2009 and never really got to spend much time at Experimental Intermedia, even when the homies from Napoli were in town to play there. When I come home it’s often family oriented stuff, but his influence is everywhere, on both sides of the Atlantic. I’ve been a big fan of Niblock’s work for many years, I forget when but somebody recommended Four Full Flutes to me, and Young Person’s Guide…. And I remember when Touch Strings came out in 09, it may have been around then, I’m sure we reviewed it for The Silent Ballet, but I was quickly sucked into to this crushing and singular approach to sound. And his films as well, again akin to a visual drone that speaks to the dignity and drudgery of manual labor.

It’s been beautiful seeing so many touching tributes on the timeline since yesterday. EI has been hosting events for more than 50 years, and Phil’s career is even longer. Despite turning 90 last year he still kept a full schedule and barely showed any signs of letting up. A true inspiration as an artist, a mentor, a cultural connector. I’m so bummed I didn’t make it to the solstice concert a couple weeks ago, yet another casualty of this winter of sickness. But we still have the music and films and memories, and the connections he facilitated will continue to multiply and his influence will live on. RIP Phill Niblock.

REVIEW COMPILATION

Phill Niblock ~ Touch Five (2013)

A very interesting strain emerges from an interpretation of Phill Niblock‘s works as essays on organization, not only of sound but of people’s relations to it. In this sense, Niblock’s association to minimalism becomes relevant, not so much in its musical division but its visual arts parallel, in which there is a marked focus on the (perceptual) experience of constituting a space and time, delineating a sculptural conception that banishes any and all determination on the part of an artistic tradition that relies ultimately on the object itself. The scale becomes larger and wider as the gaze melds the object with the place it is in, developing a multitude of relations between spectator and matter that aim for a gestalt: the wholeness that surges from looking at a structure previously unseen, the sudden realization of a fundamental rhythm.

Niblock’s music mirrors this kind of heightening of structural relations, which, because in music the ‘object’ is ephemeral at best, non-existent at worst, follow from having a particular interface in the form of sound equipment. In the first disc, by using ProTools or tapes to multi-layer tracks of a few tones played by different instrumentalists, the artist directly deploys a ‘naked process’, except different to Steve Reich’s own concept of process in the widening of the stakes to include what lies beyond it, the listener’s own gear, living room, the things that it contains, or the place through which he or she is moving. A common suggestion is to listen to his pieces at very high volumes, or in other terms, at volumes in which the sound acquires sculptural qualities, making speakers vibrate their intensity into tables and walls, modifying the surroundings enough to reconfigure the listener’s relations to them, drawn to a holistic experience that re-organizes time/space so that sound itself becomes the key to grasping structure. This is perhaps the reach of the microtonal, constantly explored by the artist, as the de-composition of a series of illusory statements (melodic, atonal, etc.) into the bare life of the purely aural. At its most detailed it makes sense of what is present before the listener, as is most easily tried out by moving around or switching things’ places just to see how this massive ‘ambience’ of drones connects it all anew.

In the second disc, “Two Lips” is rendered thrice by different guitar quartets, under specific directions to play two scores simultaneously for 23 minutes. Each score is divided into ten parts, which are then distributed randomly amongst musicians of the ensemble, in turn divided into two groups but not separated spatially. The musicians are tuned by hearing, through headphones, tones played from a tape. In a way, this tuning reduces the distance between the album and the listener, for the interface is very much the same, or at least comparable in its mechanical aspect. While in the works of composers such as Conlon Nancarrow the mechanical could be conceived as the structure itself, in Niblock’s it is the access point, the element through which a certain order comes to the fore as sheer experience of the moment. Therefore, it is possible to see how in Nancarrow’s pieces it is difficult not to perceive a near-endless atomization, one that is not blurred but highlighted by break-neck speeds; in music like “Two Lips”, perceptual separation is annulled, because even if the same tone was played faster time and again the whole would remain as such – relations shift, but the structure stands, and rearranging the musicians by score group or not becomes, in the act of producing the music and listening, almost irrelevant. This is, of course, not to say that everything remains the same, but to say that while “Two Lips” sounds completely different each time, by each of the quartets, it is still unmistakably the same piece, since what has changed is not the score, the parts, or the players themselves, but the relations between them.

This is, I think, the invitation this music makes, to listen to more than the volumes being spoken and focus on the connections they deploy to constitute a place and hour, the microtonal processes that make our living rooms our living rooms, the angles at which speakers fill an entire street but nonetheless can’t be heard at all if standing at some weird position, and the experience that plays it all out as the perception of something fundamental. This is also why I think Niblock, aged 80 this year, is more than worthy of our continuous attention, because even if other minimalists have moved on elsewhere, he’s still changing the referents of minimalism, making them seem as fresh as they ever were. Hopefully, he’ll keep droning for a long time, and hopefully, we’ll be there to listen to each and every microtone. (David Murrieta)

Phill Niblock ~ Music for Organ (2020)

Phill Niblock has a penchant for anagrams, as this record makes clear with the names of its two compositions, “Unmounted / Muted Noun” and “Nagro (aka Organ)”. In the same spirit, I note that Music for Organ might be rendered “a coursing form” – an apt description of this music. The sounds flow and accumulate like a steady, impassable river. Since they seem not to be constrained by any traditional formal progression, the structure of these pieces is itself a coursing flux.

Niblock is a stalwart of minimalist composition, active since the 1960s. His trademark approach is to record continuous tones from an instrument, then layer up adjacent microtones to create billowing clouds of sound, which soon turn to raging storms. This used to be achieved on tape, by getting the musician(s) to retune to exact pitches, sometimes specified in hertz. Niblock’s compositional task was layering up the tones to reach the final product. In recent years, Niblock makes greater use of digital processing to adjust the pitch of the source material, layer after layer.

The closest Niblock has come to crossover success seems to be Touch Food (2003). This album is a good example of his style. Its ambient droning gradually gains intensity early in each track. Then a plateau emerges in the subtly shifting microtonal surface. It may sound sacrilegious, but it almost doesn’t matter what instrument is being played on many of Niblock’s compositions. The drawn-out, stratified tones are quite removed from usual instrumental practice. “Nagro (aka Organ)” is an example of this effect; some moments could easily be bagpipes, for example.

“Unmounted / Muted Noun” alters Niblick’s usual sound. It is irrefutably a pipe organ composition from the first moment. (Specifically, both tracks feature Hampus Lindwall playing the organ of Collégiale Sainte-Waudru, Mons, Belgium.) The tremulous cadences of church music get stretched into a gorgeous twenty-four minutes. Since the pipe organ has a particular aptitude for emitting and reshaping multiple tones at once, it’s not clear where the capacities of the instrument end and Niblock’s layering begins. To complicate matters, both tracks on the album feature pre-recorded tape in addition to the live organ. However the variables come together, the result for “Unmounted” is more monolithically and satisfyingly noisy than any other Niblock composition I know of.

The remit of this review is to provide A Closer Listen. However, Niblock’s work does not willingly reward such careful attention. This composer’s raison d’etre is to explore the visceral impact of sound. He advises that his compositions be played very loud, their vibrations filling the space and affecting the listener physically more than emotionally or intellectually. I’m not entirely convinced by that rhetoric. However, I do know this record packs a powerful droning punch. (Samuel Rogers)

ACL 2020 ~ Top 10 Drone (blurb)

Phill Niblock ~ Music for Organ (Matière Mémoire)

When we consider minimalism, we think repetitious melodic phrases, cyclical rhythms, or ethereally shifting drones. Compared to these hallmarks, Phill Niblock’s music is even more minimal than minimalism. Over the decades, Niblock has employed numerous instruments in building dense thickets of sound. They seem as monolithic as the block of colour in Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square, until we attune ourselves to the continual interplay of microtonal layers. With its liturgical timbre, Music for Organ is a slight departure in an exciting direction; but it’s also a beguiling (re)introduction to Niblock’s style. (Samuel Rogers)

ACL 2020 ~ The Top 20 Albums of the Year (blurb)

Phill Niblock ~ Music for Organ (Matière Mémoire)

The then 86-year old artist snuck in this massive record just shy of New Years, so let’s count it as a 2020 release. Niblock has been a fixture on the scene since the ’60s, his NY loft still an important venue. But when he switched from working with tape to ProTools, his music became more aggressive and dense, his penchant for maximalism sought out new potentialities. The two compositions on Music For Organ are in some ways a departure from his more recent work, more static and less muscular. In fact, both compositions are live recordings of organist Hampus Lindwall accompanied by pre-recorded tape layers from other organs, each with anagramic titles. The playfulness of the titles isn’t reflected in the music, however. The mass of organ drones and overtones are best at high volume. (Joseph Sannicandro)

Phill Niblock ~ Muna Torso (2023)

Given the long history of collaboration between experimental music and the visual arts and film, it’s no surprise that a lot of music we cover on this site was designed in to be presented alongside a moving image.

The composer Phill Niblock self-identifies as an intermedia artist, working across music, film, and photography. Although often used interchangeably with other terms such as multimedia, intermedia was originally coined by the artist Dick Higgins to describe work that was truly between media. Rather than another means of describing a multimodal art like cinema, Higgins was more interested in art that fused its various media not just formally but conceptually. Writing that strove to become painting (what he calls abstract calligraphy) or video that aspired to be music, as examples.

Intermedia is the perfect lens through which to understand Muna Torso, an audiovisual work resulting from the long-term collaboration between Niblock and the choreographer and dancer Muna Tseng. The video and composition released earlier this year by Room40 is a distillation of a longer performance project the pair produced in 1992.

According to Room 40 label founder Lawrence English, Muna Torso is one of the only compositions in Niblock’s extensive oeuvre to use synthetic sounds. The twenty-one minute piece is comprised of several drones with the timbral qualities of acoustic instruments like horns and strings. Over the course of the piece their layered, sustained tones rarely modulate or break off. While their sound is relentless and ominous it is also and perhaps inevitably, absorbing. The drone’s dissonance initially seems to exist in stark contrast to the undulating body of Tseng, the sole subject of the work’s accompanying video. It takes a few seconds of watching to realize the object the camera pans around in the black and white video is Tseng’s torso shot in an extreme close-up. Throughout, the camera traces the outline of her body, focusing on the torso, but also capturing the spaces between arms and torso as the body twists and shifts against a stark, glowing white.

Tseng’s sensual sway is gentle, occasionally speeding up restlessly as the instruments stretch both our, and seemingly Tseng’s, ability to maintain interest. She, like the listener to Niblock’s drones via headphones, seems at times to struggle with what to do with her body. At times it seems to respond more intuitively to the music, at others her body conveys a sense of hesitation. The sustained harshness of the works’ sound is, however, mellowed by the body’s motion, which we never see in its entirety, as it fills the frame of the camera.

Muna Torso taps into the long history of collaboration between experimental musicians and dancers (thinking especially, of course, of John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s decades long partnership.) It’s fascinating to watch a body responding to Niblock’s relentless droning. The way it shifts between movement and stasis. Although it is never completely still, there’s a marked contrast between the moments in which Tseng’s body speeds up and slows down, even as the tempo of the drones remain (mostly) the same. As Muna Torso draws to a close the camera gets increasingly lost in Tseng’s body, the light of the white backdrop often slipping from view just as her body did in earlier moments. (Jennifer Smart)

MISCELLANIA

Organ Reframed 2017 (excerpt)

Phil Niblock’s “Thinking Slowly” was a twenty-three minute drone: one long drone that felt like a glimpse of a discordant, dislocated heaven. There was a ratcheting up of the tension, a trance-like momentum but imbued with a subtle disquiet. One elongated note was played on the harp, and the flute brought in a recurring, higher and sustained note. It showed just how versatile the organ can be. “Music In Fifths”, by Philip Glass, heightened that with its minimal use of notes, all of them in the higher register. This reminded me that the organ can, as Claire had said in my interview with her last week, be an instrument of elegant, melodic design, caring for higher, more delicate notes and feelings as well as pumping out rich chords and red-blooded, stronger textures; the depth of the instrument has no boundaries. It contrasted the lower, deeper drone of “Thinking Slowly”, and although the flute had retained its airy timbre on that piece, Phil Niiblock’s drone was like a lowering of the mood, a lowering of the atmosphere, and it was necessary in showing the versatility of the organ. The cyclical, spherical repetitions of “Music In Fifths” were like variations on a theme, a continuous sound with no space whatsoever. Psychedelic effects caused the images to shape-shift, morphing and disintegrating during the more frenetic parts. (James Catchpole)